I chose the case on The Counterculture in Court, which features two different items. The first is the ninth and twentieth issue of The Floating Bear. This was a newsletter that published Beat writers and was edited by poets Diane di Prima and LeRoi Jones. The editors were briefly arrested but eventually won the battle in court to published the newsletter, which prompted the cover of the twentieth edition, saying “Hello Ma, I Glad I Win!” The second feature was of The Love Book by Lenore Kandel. This erotic collection of poetry was seized by police in 1966 for violating obscenity laws. This helped to sell the collection and eventually it was found not to violate obscenity laws, prompting Kandel to donate a portion of profits to the Police Retirement Association, as the lawsuit helped the book succeed. I picked this case because I have always found the role of the courts and law in cultural revolutions interesting, possibly because my father is a lawyer. The idea of defining what is obscene is a challenging question and it was legally decided in 1973 in Miller vs. California, meaning these cases against Beats writers are part of what set the stage for a formal definition. To me, this raises the question of how the Beats movement tied to the larger discussion of obscenity in America at that time. To answer this, I would need to do more legal research, possibly looking more specifically at the actual court cases of Beats writers, as well as cases outside of this movement. This connects with many of the poems we have looked at that focus on social change because at the root, the Beats Movement is challenging the mainstream culture. I was already interested in looking at Alice Walker’s activism through her work, so the entire exhibit was interesting to understand how to go about telling a story about activism, both by framing the social context and the long-term implications of such efforts. Although I will be focusing on one person, not an entire movement, it was a good reminder to try to show diverse examples that focus on various different themes. For the Beats exhibit, this came in the form of discussing topics like the courts, conscientious objection, and how many influential Beats writers came together.

Month: November 2017

Kerouac and Travel: The Road to Acclaim – Devon Bombassei

Although I was captivated by many cases and installations within the Beats Exhibit, I was particularly drawn to the cases centered on Jack Kerouac, and his literary inspiration. I was immediately struck by the lone, ragged backpack, or “rucksack,” sitting staunchly in a clear case. While subtle, this military rucksack, for Kerouac, came to symbolize the greater theme of constant movement; in turn, it became a symbol for one of his principal literary inspirations: travel. In addition to the prominent theme of travel, another key feature the case displays, in a more nuanced light, is the pervasive value of community in Kerouac’s career and life. While the rucksack was just a means permitting Kerouac to constantly be on the road, or in the service, it more significantly permitted him to be apart of different communities, and friendships, along the way. To this end, I was captivated by the ability of a single inanimate object to convey deep, and substantial, themes intersecting Kerouac’s constantly moving career and life.

This case, and the way it focuses on “spontaneous prose” and movement, relates to our study in class of the fragments and collage unit. In essence, just as Kerouac drifted through many towns, even countries, his prose mirrored such spontaneity and unconventionality, uniquely defying form. Kerouac’s work can be looked on as a collage of experiences transcending his travels, and the communities he passed through as he went. In addition, when we studied many of the poems that defied conventional form, they shared the same reverence for “white space,” or leaving space open in the body of the poem to permit the reader to breathe, and subsequently reflect. Similarly, Kerouac believed the open road, one of his greatest literary inspirations, to symbolize freedom, an open future, and endless possibility. This reverence for the white space or “possibility,” furthermore, is mimicked in his writings, and in the poets we studied in class. Moreover, I will use this exhibit to help me structure my own virtual exhibit for my final project by incorporating short quotes, images, and themes/ inspirations that have greatly impacted the poet, as is done in Kerouac’s exhibit.

Some of the questions this case raises for me are as follows:

- Besides “soul-searching” and an affinity for the “open road,” were there other, more pressing, reasons that brought Kerouac to the road, or a life of travel, and that subsequently inspired his writings?

- Could Kerouac’s travels have been inspired in some way by the prominent counterculture of the time? For example, did he travel to escape? To rebel?

To satisfy my curiosity regarding Kerouac’s purpose on the road, and his search for meaning through travels, I would research through his novels and other writings, and look for significant clues into his reasons for travel. In addition, I would look for quotes potentially by family members, or even friends, that might lend insight into the reason why traveling was such a prominent calling in his life, and inspiration for his writing.

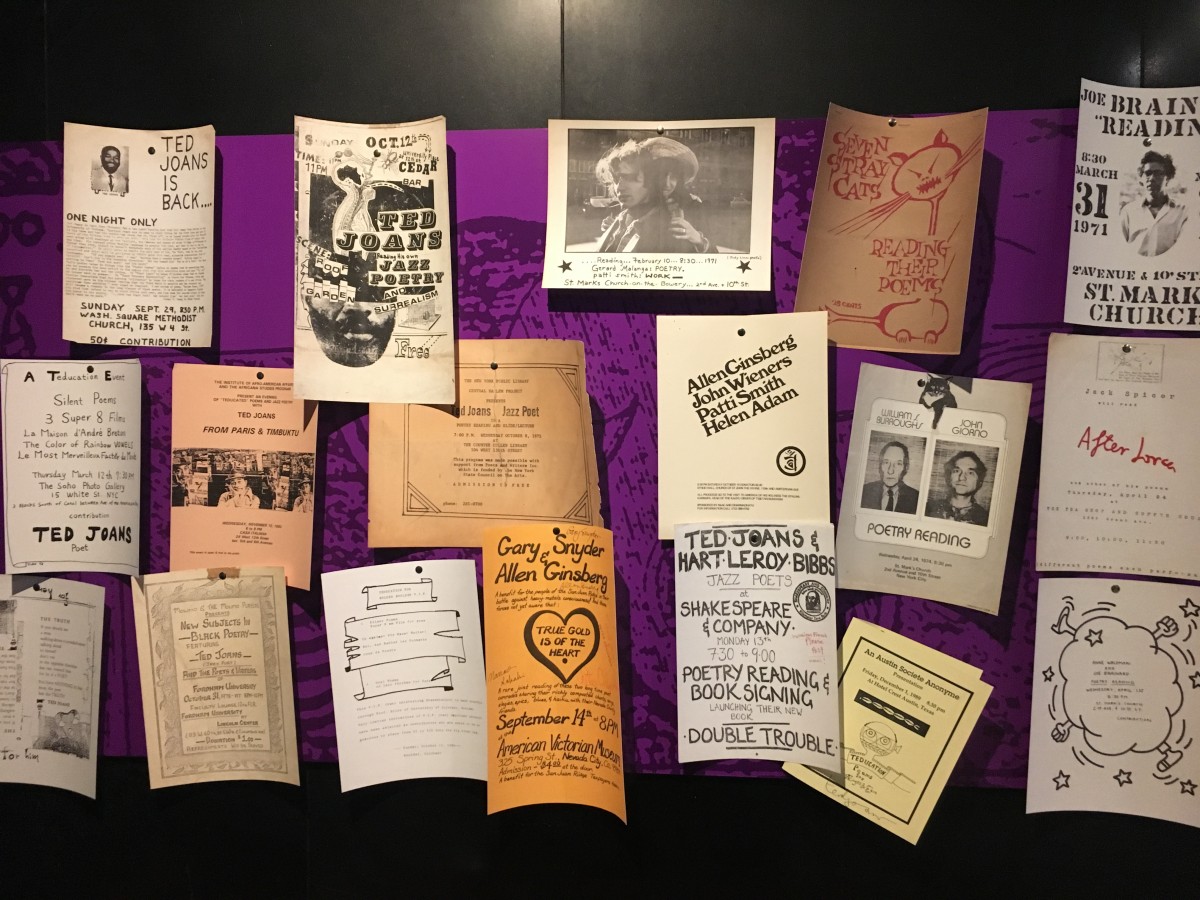

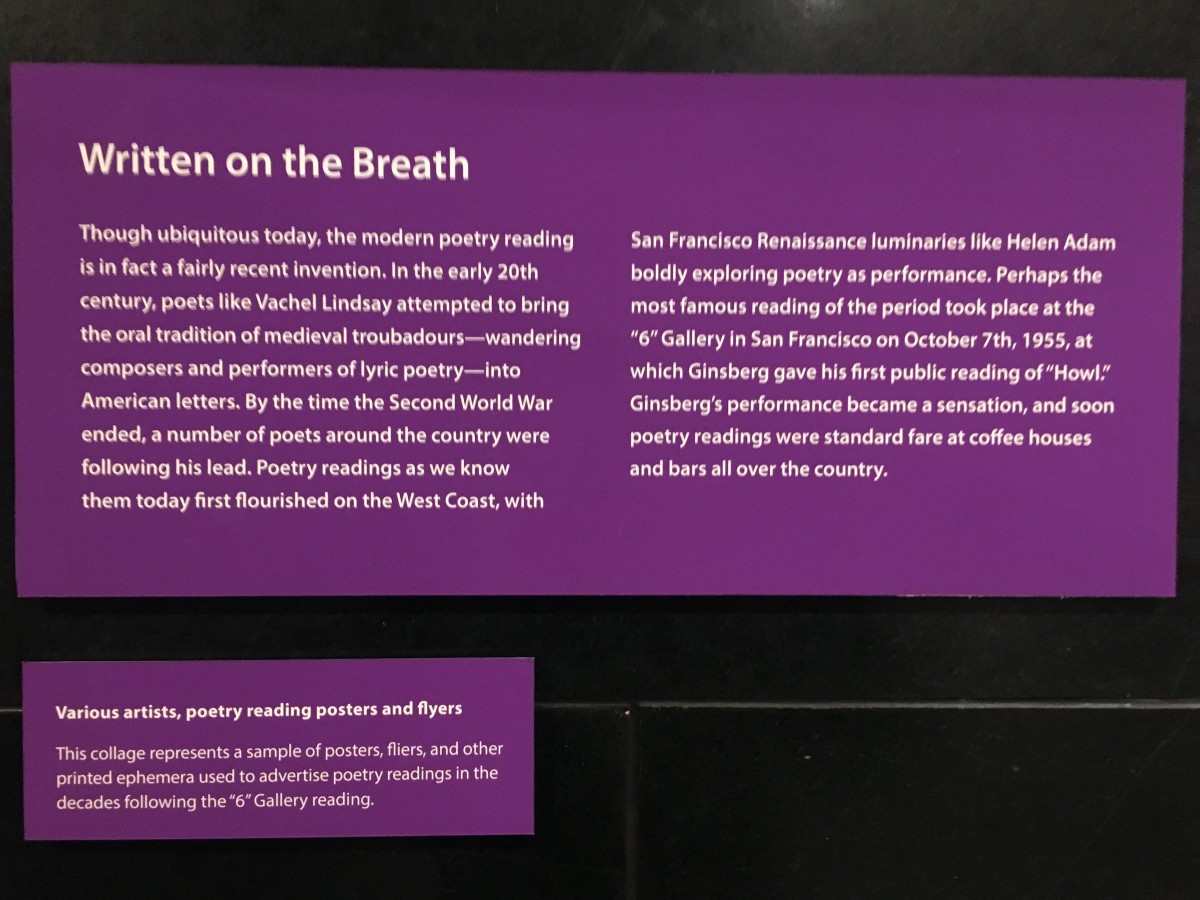

The Sound of Poetry — Colleen Su

The object that I chose is “Written on the Breath”. It is a collage of poetry reading poster of various artist and poets. The collage mentions that even though poetry reading is very common today, it, in fact, flourished only recently after World War II with the Beat Generation. I was drawn to this case because after I went to the literary event “‘Howl’ at Emory”, in which Emory faculties and students perform Ginsberg’s “Howl” and local poets read their own Beat-inspired poems, I truly felt the difference between reading poems and hearing them. Hearing the poem engenders more intense emotion than merely looking at them, and depend on the reader’s voice, the audience might pay attention to things that they did not notice when they were reading the poem.

This case reminded me of the guest speaker we had in class that performed Ted Berrigan’s poem which was accompanied by a film clip. We also watched many videos of poets reading their own poem, such as Ocean Vuong’s “Night Sky with Exit Wounds” and Marlene NourbeSe Philip’s “Discourse on the Logic of Language”. All these experiences made me think that reading is not the only way to appreciate and understand poems, sounds also matter.

This case gives me inspirations on my final project because I always thought one case of an exhibit can only contain one object, and I never thought of using the form of collage to include various materials that address similar topics. Furthermore, after looking at the exhibit, I realized that the materials included in an exhibit can be very different. It can range from actual poems and magazines published during that period to personal items like love letter and passport of the leading figure of the movement. A wide range of materials can be included as long as there is an overarching theme that ties all the pieces together.

After looking at the case, some questions I had are that why is poetry reading only started recently considering that poetry writing has such a long history, and what made poets start to realize the importance of poetry performing? To answer these questions, I would need to go search online or from the library the history of poetry. I also need to look up the beginning of the Beat movement to see what inspired the poets to start poetry reading.

Cutting Up to Building Up – Claudia Tung

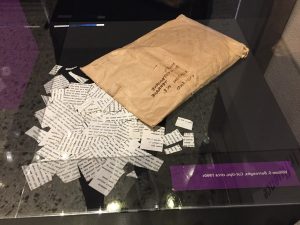

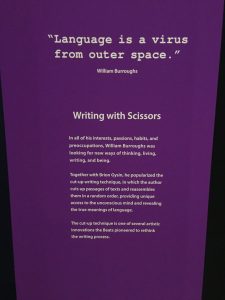

The case that I chose is called “Writing with Scissors”, and the object on display is William Burroughs’s cut ups in a folder from circa 1960s. There are lots of different sizes of squares and rectangles of paper with words from many passages of texts. This case first drew me to it because it just looked strange and interesting because I wondered why someone would cut up passages and what they were planning to do with the squares.

Although this case talks about a technique called the cut-up writing technique, it reminded me of the works by Ted Berrigan and Medbh McGuckian. During one of our MARBL visits, we saw Ted Berrigan’s process of scratching out words from a book to create an entirely new work. During class, we also saw how Medbh McGuckian would choose bits and pieces from other poems/works to forge her own poem. Both of Berrigan’s and McGuckian’s work “borrow” words/phrases from other work, just like what Burroughs was doing with the cut-ups. These are all examples of intertextuality, which I think is a very creative and innovative way to create your own piece of work. This installation gives me ideas on how I might structure my own virtual exhibit because the Beats Exhibit allowed me to see how bits and pieces of artwork are insights to the artists’, poets’ or writers’ character and thoughts, and that they create these kinds of work for a reason. The exhibit gave me an idea on what types of materials I should be looking at for my poet to really get to know her and put together a meaningful virtual exhibit.

Some questions that came up after looking at this installation at the Beats Exhibit were: how did Burroughs choose which passages to cut from? How did he put the cut ups together? Did all the phrases on the square have to match with the other phrases from another square or did he only do one line at a time? I would love to read a collection of Burroughs’s work along with where and how he got his sources. I want to discover how he approached this intertextuality technique and what kind of new texts he liked to create. Through these examples of his work, I can look into this train of thought as he puts together the cut-up passages. I would most likely have to look at scholarly books if I want to also read about the sources of the texts. I am also aware that there were past exhibits in museums, such as the Irish Museum of Modern Art, that showcased Burroughs’s work. I would love to attend one of these exhibits to learn more about Burroughs’s creativity and ideas because it really is a unique approach to writing.

Tu 11/21 & Th 11/23

Tu 11/21: RESEARCH DAY— No scheduled class. Instead, this day will be reserved for research, your final visits to the Rose Library, and conferences with me (as needed)

Th 11/23: THANKSGIVING DAY—No class. Enjoy the holiday!

Th 11/16: Poem as Archive: Metonymy

Tu 11/14: Poem as Archive

Read Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, focusing on the first half of the book. As you read, consider our previous class discussions of archive and memory, collage and fragment.

Beats’ Exhibit blog posts due to the website by 11:59 p.m.

Cultural Connections in Beat Poetry)

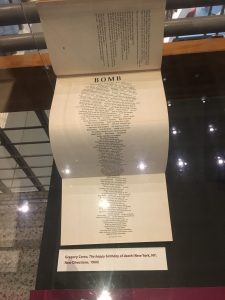

I have chosen the Beat Hotel case, which feature a poem by Gregory Corso entitled “Bomb”, the notes of the poet Brion Gysin from his time at the Beats Hotel, and a collection of poems by Allen Ginsberg in a book entitled Kaddish. These items are products of a unique culture that spring from a no-name hotel in Paris during the 1950s and 60s. These poems were written by poets who were inspired by their culture and the events around them. Kaddish is a collection of poems inspired by the Jewish prayer for the dead. This was written as an elegy for his mother. The poem “Bomb” is a poem written in the shape of a mushroom cloud, written during the Cold War to highlight the threat of nuclear annihilation. I was drawn to the case because of the unique method in which the poetry was constructed.

The poems, as mentioned before, lack a conventional structure. This presents fascinating insight into the construction of the poem. The texts in this case provide a fascinating glimpse into the culture around which the Beats Generation was created which lead up to the Counterculture movement. Reading the poem “Bomb” and Gysin’s notes from the Beats Hotel remind me of the poem “Map of the Americas” by Qwo-Li Driskoll. In this poem, he creates an image of North and South Continents, displaying an inextricable link between the people living in the continent, and the la nd itself. Similarly, E.E. Cummings experiments with the format of his poem, creating a work that makes very little sense on its own. We are forced not to look at the words that are written on the page, but the meaning behind the format. Similarly, the notes by Gysin and the poem “Bomb” are written in free verse, putting emphasis on the meaning of the shape of the poem. The inspiration for the poem not only come from the culture of the poet w

nd itself. Similarly, E.E. Cummings experiments with the format of his poem, creating a work that makes very little sense on its own. We are forced not to look at the words that are written on the page, but the meaning behind the format. Similarly, the notes by Gysin and the poem “Bomb” are written in free verse, putting emphasis on the meaning of the shape of the poem. The inspiration for the poem not only come from the culture of the poet w as raised in, but also from the inspiration drawn from his fellow poets. Reading these poems, I think I have a good idea of how I can structure my essay. Using an overarching stylistic connection, I will examine how the poet’s works are connected across poems and the underlying cultural influences which lead the poet I have chosen for my final project to adopt the particular style and format for his poem. I will also examine the underlying cultural influences which lead my poet to publish his works as he did.

as raised in, but also from the inspiration drawn from his fellow poets. Reading these poems, I think I have a good idea of how I can structure my essay. Using an overarching stylistic connection, I will examine how the poet’s works are connected across poems and the underlying cultural influences which lead the poet I have chosen for my final project to adopt the particular style and format for his poem. I will also examine the underlying cultural influences which lead my poet to publish his works as he did.

I am fascinated with the political and cultural influences on the Beat Generation at the time, and would love to explore how the Beat Generation has or has not affected the inhabitants of the Latin Quarter. I would collect information online about Paris in the middle of the 20th century and search documents online to determine whether these poets had an intellectual affect on Parisian culture.

Appreciating Absurdity-Katie Flaherty

I’ve chosen the case containing Jack Spicer’s mimeographed newsletter “What to do with the Boston Newsletter” and Bob Kaufman’s “Abomunist Manifesto”. As its title suggests, Jack Spicer’s work is a faded list of ways to handle the Boston Newsletter. He proclaims that readers must share or destroy the newsletter; they mustn’t keep it. Considering that many people collect newsletters, these clear instructions seem almost ridiculous. Continuing on the theme of absurdity, Bob Kaufman’s “Abomunist Manifesto” demonstrates how “abomunists” reject conformity and normalcy of all kinds including pain and debts. Together, these works show a clear refusal to accept convention, habit, and commonness.

I was initially drawn to this case for 2 primary reasons. The first being that I grew up in Boston and enjoy literature like “What to do with the Boston Newsletter” that references my beloved city. Additionally, I immediately drew a comparison between the “Abomunist Manifesto” and my favorite book: George Orwell’s “Animal Farm”. Bob Kaufman’s list resembles the seven commandments put forth by the pigs in “Animal Farm”, which are based upon the Communist Manifesto. All three possess an odd and somewhat ridiculous sense of confidence and authority.

Furthermore, this case reminds me of our class conversation around line, syntax, spacing, and how poems appear on the page. Jack Spicer’s publication consists of numbered items separated by large spaces. I believe that Jack Spicer chose this format in an effort to represent his opinions as definite instructions, similar to those included in every game box. Readers are accustomed to following numbered steps and therefore Jack Spicer’s numbering provides authority. Similarly, Bob Kaufman demands authority through the use of capitalization in the first section of the “Abomunist Manifesto”. In this section, every letter of every word is capitalized to call attention to its importance. Also, Bob Kaufman writes the capitalized lines in parallel structure so that the content is easily accessible to the ordinary reader. The coupling of these structurally authoritative poems inspires me to organize my final project by unspoken content and themes.

My inspection of “What to do with the Boston Newsletter” and the “Abomunist Manifesto” leads me to question how these publications were initially received. Nowadays these works seem rather absurd, but were they ridiculous in their own time? Were these writers appreciated or shunned? To answer these questions I must garner a greater understanding of the political climate of the late 1950s. By understanding the parties, conflicts, and priorities of the time, I would be able to discern how these works fit into 1950s culture.

Breaking the English Language Conventions — Claudia Tung

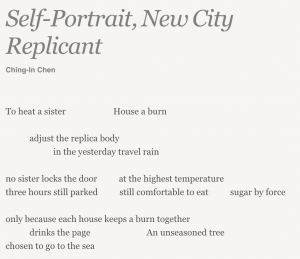

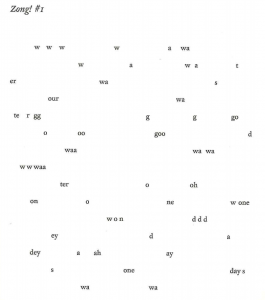

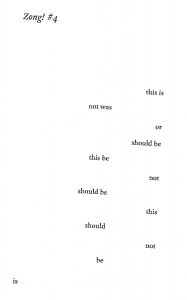

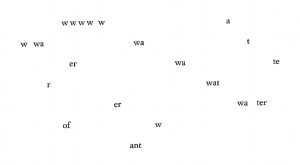

“Self-Portrait, New City Replicant” by Ching-In Chen (Nov. 1 Poem-a-Day) is like a piece of work where Marlene NourbeSe Philip and Gertrude Stein collaborated on. It follows unconventional grammar and syntax structure that makes it difficult for readers to interpret the poem without deeper analysis, much like the poems by Philip and Stein. More specifically, Chen’s poem reminds me of the poems in Zong! by Marlene NourbeSe Philip visually. The structures of the poem are similar because both poems utilise enjambment and don’t follow a specific meter, and there are no coherent sentences in either works. Both poems have words scattered around the page with large spaces in between the words, and they don’t link up to create proper sentences. However, there are some differences between the poems. For example, the poem by Ching-In Chen is slightly more cohesive because there are phrases scattered around the page, while the poems in Zong! can have words, letters, or phrases scattered around the page, which looks messier and even more disconnected.

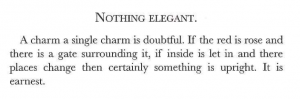

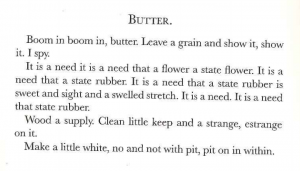

“Self-Portrait, New City Replicant” also reminds me of Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons because of the way the poet writes the phrases. Although some of them make sense, there are a few that are rather unorthodox. For example, “adjust the replica body”, drinks the page” and “in the yesterday travel rain” sound like phrases that Stein would write because of the way the phrases are formed. They don’t follow the normal sentence structures and they don’t make sense as a phrase. In addition, Chen writes about different and unrelated things throughout the poem, like Stein does. For example, he talks about heating a sister in the beginning, being comfortable to eat in the middle and an unseasoned tree at the end. None of these sentences go together, like the poems in Tender Buttons. Just to show a comparison, Stein would write things like “boom in boom in, butter”, “wood a supply” and “it is a need that state butter” to describe butter.

Poems like these have always made me wonder what poetry is defined as. There are always a few questions that come along with these unconventional poems: how do the poets even come up with these kinds of phrases? How are we supposed to make sense of them? Why do they write like that and what are they actually trying to convey? As a student without a real talent in poetry, it makes me think that I could write random sentences and become a successful poet because people can interpret my random sentences their own way and assume that it is what I intended to express through the poem. However, I’m sure that there is a much more complicated and meticulous process that goes on behind the poem, which I would love to learn about through personally interacting with the poet.