Alcohol holds a unique connotation in every person’s mind. For some, it means a casual drink on a Friday night. For others, it’s a family-plaguing disease. To chemists, it’s a functional group, to rocket scientists, it’s a fuel. But for most members of society, alcohol is a drug taken to get drunk. Surrounding the popular anxiolytic is a cloud political debate, perhaps the most thunderous being the debate over the legal drinking age in the United States. In 1984, Congress passed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act, requiring states to have a minimum legal drinking age of twenty-one in order to receive full highway funding from the national government. The reasons for this action are grounded in and supported by science and research. Many people feel that the drinking age is too high, that it should be lowered to eighteen. A small few even feel the drinking age is too low, lobbying for a twenty-five year old drinking age. However, the twenty-one year old drinking age protects adolescents from brain damage, decreases the risk of alcoholism, and significantly lowers drinking related fatalities. Furthermore, the arguments pushing for a lowered drinking age generally lack scientific evidence and/or are grounded in myth or misinterpretation. It is for these reasons that the drinking age should remain at twenty-one.

Before discussing the literature on both sides, it’s important to understand what this argument is about and what it’s not about.

- It’s not about who is allowed to drink, it’s about who is allowed to purchase alcohol. The average age of first consumption is twelve however the drinking age is twenty-one.

- This is an argument meant for politicians and the uninformed public. Politicians are not scientists, however they are responsible for the laws governing the safety of US citizens. Many people form an opinion on this topic without access to appropriate studies and information.

- There is still much more research to be done. A lot of studies include speculation. A new finding could be published and completely alters the way we view alcohol.

Alcohol is a depressant and its mechanism of action involves the upregulation of the inhibitory neurotransmitter, GABA, and the down regulation of the excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate. This causes a depressive effect on the brain and body. In adolescence, the brain is still maturing, specifically the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center. Sure enough, when comparing the hippocampal volume between adolescent drinkers and adolescent non-drinkers, the drinkers’ hippocampus was significantly smaller (Ziegler et al., 2005, 27). In addition to being the brain’s memory center, a smaller hippocampus has been linked to depression. This damage to the adolescent brain is dangerous enough, but alcohol’s effects on adolescents do not stop there.

When considering the danger of a drug, it’s imperative to look at how addictive that substance is. Alcoholism is the most common drug addiction worldwide and can cause major damage to organs and organ systems. The shear nature of alcoholism is contentious. There has been evidence showing a genetic component to alcoholism, explaining why it runs in families (Borson, 1986). What’s possibly even worse than alcoholism is alcohol withdrawal. Due to the nature of the mechanism, once withdrawal begins, there is a bounce-back effect, which may result in death (Trevisan et al., 1998).

In terms of the legal age limit, those who support lowering the drinking age argue that alcoholics will be alcoholics no matter what. While this appeal to the genetics behind alcoholism may be factual, it has been proven that early use of alcohol, specifically in adolescence has been linked to later alcohol and drug abuse (Spear, 2000). With a lower drinking age, a trickle-down effect occurs. With a drinking age of eighteen, high school seniors could purchase alcohol for their younger friends, putting more youth in danger of developing dependencies later in life (Wagenaar & Toomey, 2002, p. 221).

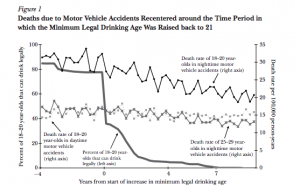

The item that comes up most often in the legal drinking age debate is the number of driving fatalities and other alcohol related deaths. It’s difficult to analyze data on this subject because we can’t perform an experiment of this kind. We can’t compare ourselves to other countries because we have different drinking habits and culture. So the most controlled way to quantify this data is to look at the years before and after the change of the legal drinking age nationally. In Figure 1, there is a downward trend in deaths of eighteen to twenty year olds in the years following the National Minimum Drinking Age Act.

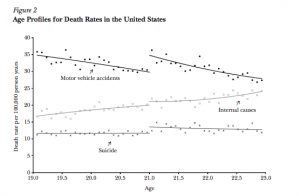

Unfortunately, the story doesn’t end in driving accidents. Alcohol is also a common tool in suicides. Current studies show an interesting correlation between age and cause of death.

What’s so interesting is that the data shows two regression lines for two separate age groups, suggesting that once people reach a certain drinking age, they are drinking and we see a discontinuity in death rate. Some suggest that lower the drinking age will not only raise the rate of motor vehicle accidents, but all alcohol related deaths, including suicide (Carpenter & Dobkin, 2011).

As stated in the beginning, there is a great lack of scientific support for lowering the drinking age. A very common plea is “I can fight in the military but I can’t drink?” The United States has many age restrictions (driving age, voting age, age of consent). The US military is searching for willing, healthy men and women, and has determined eighteen to be a suitable age to serve, whereas the twenty-one year old drinking age takes science into consideration and aims to protect lives.

Another common argument is “Lowering the drinking age will diminish the binge drinking in high schools and decrease crime.” While its true that eighteen to twenty year olds would no longer get in trouble for underage drinking, but due to that trickle-down effect, more adolescents will have access to alcohol, which is a strong contributing factor to dependence later on in life. As far as crime, there has been no evidence to show any true change in crime.

There are those who believe a higher drinking age of twenty-five might be the ideal solution. The thought behind this idea is that the brain is not fully developed until it is twenty-five (Courchesne, 2000). Until then, alcohol would interfere with its growth and development. This reasoning is sounded and rooted in scientific evidence, however, only very few people subscribe to this side of the argument and does not receive much support

While the legal drinking age debate is important, what’s even more important is alcohol education. Age is not the only factor contributing to alcohol-related deaths. The US has one of the highest legal BAC level. Teenagers are texting and driving more than ever. The current alcohol education programs in the United States are insufficient in providing students with factual information. It’s important to improve our education so that we can ensure our laws are supported by science and not by myth.

Works Cited

Bosron, William F., and Ting-Kai Li. “Genetic Polymorphism of Human Liver Alcohol and Aldehyde Dehydrogenases, and Their Relationship to Alcohol Metabolism and Alcoholism.” Hepatology6.3 (1986): 502-10. Web.

Carpenter, Christopher, and Carlos Dobkin. “The Minimum Legal Drinking Age and Public Health.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 25.2 (2011): 133-56. Web.

Courchesne, Eric, Heather J. Chisum, Jeanne Townsend, Angilene Cowles, James Covington, Brian Egaas, Mark Harwood, Stuart Hinds, and Gary A. Press. “Normal Brain Development and Aging: Quantitative Analysis at in Vivo MR Imaging in Healthy Volunteers1.” Radiology 216.3 (2000): 672-82. Web.

Spear, L.p. “The Adolescent Brain and Age-related Behavioral Manifestations.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 24.4 (2000): 417-63. Web.

Trevisan, LA, N. Boutros, IL Petrakis, and JH Krystal. “Complications of Alcohol Withdrawal: Pathophysiological Insights.” Alcohol Health and Research World 22.1 (1998): 61-66. Web.

Wagenaar, Alexander C., and Traci L. Toomey. “Effects of Minimum Drinking Age Laws: Review and Analyses of the Literature from 1960 to 2000.” Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement J. Stud. Alcohol Suppl. S14 (2002): 206-25. Web.

Zeigler, Donald W., Claire C. Wang, Richard A. Yoast, Barry D. Dickinson, Mary Anne Mccaffree, Carolyn B. Robinowitz, and Melvyn L. Sterling. “The Neurocognitive Effects of Alcohol on Adolescents and College Students.” Preventive Medicine 40.1 (2005): 23-32. Web.

Leave a Reply