Overview

| Definition and Background. What is considered “Deviant”? |

| Social control |

| The “Deviant Making” process |

| Deviance in social change |

| Personal observation: Consumption of deviance in the media |

| Works cited and sources |

In the field of Sociology, the study of deviance is centered in the behaviors of individuals and groups who differ from the norms established by power structures. Deviance is therefore a broad concept that stands for a wide range of social conducts and outcomes in a specific setting that do not conform or even confront socially settled rules to different degrees.

Definition and Background. What is considered “Deviant”?

Sociologists have developed their theories over diverse definitions of deviance throughout the years as the notion and study of this discipline evolved.

The word deviance comes from the Latin deviare “To turn aside, wander off the way (via)”

Allison Schulnik

Prior to its emergence in the field of sociology, the word deviant was used to describe individuals who stood out in social settings for their non conformity to settled standards, mainly those established by religious and governmental entities. The first uses of the word “deviant” in this science began in the late nineteenth century, with Durkheim anomie theory in the study of social disorganization, in which deviance no longer meant a defect in the individual but rather a systemic phenomenon. For Durkheim, deviance was a necessary part of communal life, in which norms were tested, producing the reinforcement of these. Alternately, since deviation challenges the norm, it is also crucial in changing it. According to Durkheim, deviant behavior rises in the absences of concrete cultural rules and values, which in turn causes a state of disarray, reason why it becomes essential in the process of establishing social structures. Half a century later, the renowned American Sociologist Robert Merton proposed an anomie theory in which the individual deviated from the norm as a way of coping with the angst felt by his inability to achieve prosperity in democratic societies where access to economic resources were necessary to reach this goal.

Although they were groundbreaking observations crucial in the development of deviance, definitions of the word moved on from ideas that implied tangible and negative outcomes (such as harm and crime) into more abstract concepts with less clear limits as to what could be considered deviant.

Most sociologists agree on a division of deviant behavior: formal and informal. The latter would stand for all things considered to go against the actual law established by the legislative body of government, which is met with legal punishment such as incarceration, whereas the former refers to conducts not accepted by the overall majority of the group that do not cross the extreme, like for example stealing stationeries from work, face tattoos or not brushing one’s teeth. Social scientists also point out that deviance can work on a macro- or micro- level scale depending on the scope of the individual’s actions and the size of the reacting group. Someone can be considered “deviant” in their own family for not abiding to family customs, but normal in a societal context where the family tradition is not relevant, or they can be considered deviant by the whole of society, like for example a serial killer.

Erich Goode (2015) described deviance as ‘matters of degree’. Actions could be considered deviant according to a spectrum of indifference and outrage, seen in the reaction they caused in the group. This result will be shaped by the general moral enterprise and ethical ideal of the group, which will also determine the importance of the norm depending on its cruciality in the form of life pursued by the dominant group which in many cases makes up the majority. Deviance can be measured by its probability of causing censure or discomfort in a variety of social settings. Thus, the definition of what is deviant adapts to time and place, as many things that are considered deviant in some societies are not in other cultural settings, and can even change overtime. Goode provided some key elements on how actions earned their status as deviant:

(1) a rule or norm has to exist

(2) one or more individuals violate – or are thought to violate – that norm

(3) an “audience” that judges the normative violation to be wrong

(4) the likelihood of a negative reaction by that audience

Keith Mayerson

An example of something causing an extreme sense of outrage following these characteristics in a specific social and historic setting, earning the label of “deviant”, is what Patricia and Peter Adler (2006) noted after the 9/11 tragedy. This event changed the definition of what deviance meant in the US, as sentiments of islamophobia and xenophobia skyrocketed and they became the general feelings of the population. It changed the public view on Muslim and Arab people forever, to a point where it influenced politics and law enforcement in the entire world. Islam was seen as something that challenged “the American dream” (In this case, the moral enterprise of the majority) as the mass media tried to frame it as something that even intended to destroy it. Therefore it became dangerous to be Muslim or Arab. Before 9/11, belonging to any of these groups was not part of the American ideal belonging to the white majority, but after the terrorist attacks it became unacceptable. The existing law and structure were defied, the audience panicked, and they applied a punishment to what was now considered “deviant” because of the violation.

Although the details of what makes something “deviant” can vary depending on which conviction is held about deviance according to its setting, there’s a general consensus that all things deviant are born out of an individual or communal defiance of an explicit or implicit law, reason why the term deviance can be applied in many instances where actions and rules considered to be a part of social stability are challenged.

Social Control

Social control is a necessary concept in the understanding of deviance. By social control, it is understood as the systemic maintenance or order, displayed and enforced by the dominant culture/group. It is with social control that the superior or governing part of society imposes its ethical desire on the other side and expects subordination.

Francis Bacon

Control can be manifested and applied in many different ways. As Costello (1997) explains, the violation of a norm is always associated with a reaction, which is usually met with a sanction that varies according to the situation. In Foucault’s conception, punishment is the cultural reconstruction of the subject (Kurzweil, 1997). The norm, therefore, implies a need for social reinforcement of positive and negative affirmations that serve the purpose of remarking the expected attitude of the individual. If there is no social reinforcement, then, there is no need to qualify that behavior as a norm. It does not conform an essential element of the ethical ideal of the presiding group. It is because of this reason that the label of deviant in the norm becomes so important in this operative, as it is what determines what is to be punished or sanctioned and allows the disempowerment and submission of the weaker group.

The oppressive group must make it clear to the subordinated group that some conducts are forbidden. According to Goode, there are 2 types of sanctions the dominant group can apply depending on the setting: social and situational. Social sanctions are usually related to the punishments applied by communal consensus regardless of the circumstances in which the violation of the norm was committed or in situations where the norm is always in place. Formal deviance for example is dealt with by social sanctions such as fines and imprisonment. On the other hand, situational sanctions are applied in circumstances in which the action was wrong in a certain context but it would have not been in another. Nobody wears colorful shorts to a funeral, but they might if they attend a Holi party. Both of these sanctions enforce social control, as they mark the limits as to what is acceptable depending or not on the situation and time. Those that carry with the deviant label serve as an example of what can happen to subjects that defy the desired moral enterprise. Punishment can be direct or indirect and correspondingly come in the form of condemnation and legal persecution or disapproval and marginalization (Costello, 1997). The importance of the norm in social stability is what decides if the digresser of it signifies a potent danger in society or if it can be simply ignored and be put aside from social life.

The “Deviant making” process

Konstantinos Koufogiorgos

As Goode explains in The Handbook of Deviance, there’s a general agreement between sociologists about a “cause and effect” principle in most anomie theories about social disorganization. This principle attributes the infinite variables in social structures and the subject’s relationship with its peers to the outcomes labeled as deviant. For example, in deviance theory, one of the main causes linked to deviant behavior is poverty, as in many cases it leads to individuals having to appeal to illegal forms of profit to sustain their lives. This way, in very simple terms, poverty would be the cause and crime the effect. Costello (1997) quotes Hirschi and Gottfredson’s work and claims that the root of non normative behavior in social settings is “a natural consequence of human nature” as “we are inclined to take the quickest and easiest means to satisfy our desires, which is often through deviation.” There’s a reaction towards the objectives of the majority, where the minority rarely fits. Cultural values and social organization always act as the trigger in deviant behavior, since in many instances it positions itself as a barrier between the individuals and their goals to fit into the structure, and it becomes a trend in a group after this pattern is repeated within a community, where said conduct will no longer be considered deviant but rather an expected outcome of stratification. Although the action will be seen as neutral in the eyes of the minority, it will not be in the eyes of the dominant group.

Costello lays out the following characteristics of the “deviant making” process:

1) values vary without limit (or at least to the same extent that crimes vary)

2) only social reinforcement motivates behavior

3) behavior is determined by an individual’s associations

From this description, it is understood that the “deviant making” process largely depends on the individual’s conformity or nonconformity with the rule imposed upon them, which will earn them the label of deviant unless the individual belongs to a group or community where their actions are neutral and even part of everyday life.

Deviance in social change

Iron thumbscrews, head squeezers, stretching racks and interrogation chairs with spikes were amongst the countless forms of torture used as penalties for non Catholics in Spain during the Holy Inquisition. Today more than half of the population openly identifies as atheist.

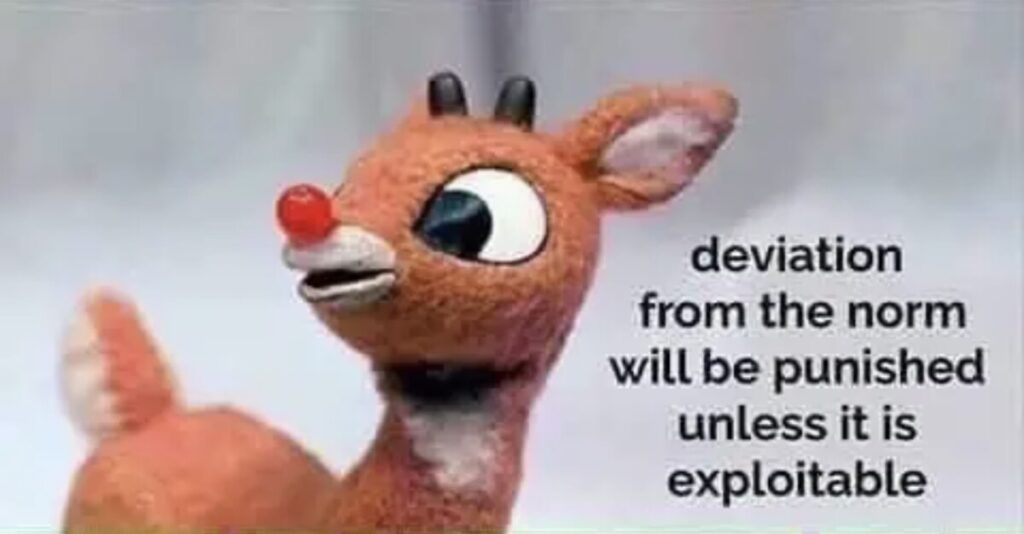

“Progress is impossible without deviation from the norm”- Frank Zappa

Durkheim attributed this shift in social norms to the disruptiveness of atypical ideas some members of the general public hold compared to those of the majority. Something stops being deviant when the ruling group can no longer oppress it (punishment is no longer viable) or marginalization is impossible (the deviant must become an integrated part of society). Thus, the quantity of people who engage in the “deviant” behavior is essential in this process, as it is in the amount of individuals who support and participate in the rebellious activities that change its status in the process of normalization. The transgression of the norm involves a disruption in cultural stability that forces the governing body to “re-think” its established laws, as ignoring or condemning the deviant activities becomes unattainable. The “deviants” are incorporated and the quality that used to make them stand out starts to be tolerated by the majority progressively over time.

A great example of social change arising from a “deviant” group is the case of the LGBTQ+ community in the last century. According to a 1965 study by J.L Simmons, the most common answer people had to the question of “What is deviant?” was “Homosexuality”, as the people who engaged in this lifestyle “deviated” from the heteronormative form of sexuality and were seen as a threat to the traditional model of family. Although still isolated and oppressed in many sectors of society, the LGBTQ+ collective made impressive advancements in the last century, gaining rights and changing the overall public view on same-sex attraction and different forms of gender identity. Today, 34 countries recognize same-sex marriage and more than 20 allow their citizens to go under gender transition. Visualization was crucial in this change, as historical events like the AIDS crisis uncovered from the shadows the lives of individuals that had been secluded from communal political life and demanded from the majority the acceptance of their existence. The majority was forced to stop turning a blind eye when it came to LGBTQ+ rights, as with time it became unviable.

Personal observation: Consumption of deviance in the media

If one were to put all commonly-known forms of deviance and marginalization into a 7 season series, the ending result would most likely be something similar to “Orange is the new black”, thought to be the first hit show on any streaming service and arguably what launched these into popularity. A show about a female prison where all main and secondary characters are women, people of color or part of the LGBTQ+ collective (with many of them having intersectional identities belonging to more than one of those demographics) apart from carrying with the obvious label of criminal, was the main sediment of the multibillion dollar company that is known as Netflix.

In “The Deviance Society”, Patricia and Peter Adler discuss Dotter’s conceptualization of deviance in the media. In movies, tv shows and many other forms of content, a “deviant” matter becomes the main plot. All of these interpretations of deviance are based on the deviant act itself and the reaction from the general public, which is then defined and reconstructed to offer a certain interpretation which leads to an idealized social control narrative. Most of the cases which follow this principle are war and crime movies, where the protagonist-antagonist relationship between characters is clearly defined by the villain carrying the obvious deviant label.

Lori Love Penland

However, this does not seem to be what happens in “Orange is the new black”. The show portrays incarcerated women as people that despite their circumstances they have not lost their humanity, in a successful effort to blur the line of what is deviant and what is normal, even rational at times. Although these women are thought to have become irredeemably “deviant” by the felonies they committed or their attitudes to others and the law, all of the events that led them there were the unfortunate but inevitable result of a system that put them in situations where transgression of the law was necessary for survival. Many of the characters were isolated from the world the moment they were born, as many dealt with intersectional oppression derived from their race, gender identity, sexuality, neurodiversity, and socio-economic status, whereas others encountered said difficulties and more (such as sexual and drug abuse) that shaped the course of their lives. “Orange is the new black” asks the viewer to question the morality of crime in a realm of empathy that is central to the answer.

But is the answer genuine?

While the characters impersonated in the show are praised and loved by fans, the real women facing unjust sentences and treatment in US the justice system are ignored and belittled on a constant basis, as many of them find reinsertion in society extremely difficult and have to deal with the same difficulties that lead the there (such as poverty, drug abuse and gender violence) once their time is over, which leads to a massive reincarceration rate that only keeps growing with time1. The difference is, the latter produce millions of dollars to a media giant, whereas the former demand actual action that cannot be commercialized or profited from. Deviation is capitalized off of in the first instance, perhaps in a way in which the viewer not only blissfully consumes the content, but the idea that consciousness about the situation liberates people in those situations of the deviant label. However, the attitude the general consumer has towards actual imprisoned women rarely lives up to this standard. Our observations of the message transmitted by the show and the reality faced by millions of women in the US leave us questioning the content we are consuming. Is it a powerful cry for change, or a strategy to make us believe that this will happen by itself? Is it the actors and actresses that then go on to elegant premiers where the actual women who they portray would not be allowed to attend? Or are we all just selfishly enjoying the exploitation of deviance?

Works cited and sources

Abrams, Dominic. “Deviance | Sociology.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 26 Nov. 2018, www.britannica.com/topic/deviance.

Adler, Patricia A., and Peter Adler. “The Deviance Society.” Deviant Behavior,vol. 27, no. 2, 2006, pp. 129-148. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/devbh27&i=125.

Costello, Barbara. “On the Logical Adequacy of Cultural Deviance Theories.” Theoretical Criminology, vol. 1, no. 4, November 1997, pp. 403-428. HeinOnline https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/thcr1&i=377

Goode, Erich. The Handbook of Deviance. Hoboken, Wiley-Blackwell, 2015. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy.library.emory.edu/doi/pdfdirect/10.1002/9781118701386

Kurzweil, Edith. “Michel Foucault: Ending the Era of Man.” Theory and Society, vol. 4, no. 3, 1977, pp. 395–420. JSTOR,https://www.jstor.org/stable/656725

Nickerson, Charlotte. “Deviance in Sociology: Definition, Theories & Examples.” Simplysociology.com, 31 Aug. 2022 https://simplysociology.com/deviance-examples-sociology.html

- “Vera Institute of Justice.” Vera, 2014, www.vera.org/research/overlooked. ↩︎