Alice Zheng

61st Street in Sunset Park, charter bus stop to casinos and Asian Pop Concerts.

Brooklyn, NY.

The Asian American Movement in 1970s New York formed upon inspiration from the Black Power Movement and anti-war sentiments primarily by second and third generation Asian Americans. The movement aimed to claim America as the Asian American’s legitimate home. This dissociation with foreign born Asian Americans reveal the generational gaps between immigrants of Asian descent (first-generation) and American-born Asians (second-generation and onward). This exhibition focuses on this inter-generational gap through musical production from activist oriented music by American-born Asians and non-western music by foreign-born Asians.

The American-born Asians in New York City dominated the Asian American Movement. In the context of New York Chinatown, the movement was a period of organizing for rights as well as a time to create a “coherent” Asian American culture. This urge to define oneself granted the creation of the pan-ethnic identity, Asian American. The term was created upon a shared history of oppression and resistance in the United States. Though meant to encapsulate the entirety of Asians in America, the movement itself was led by American-born Asians.

Thus, there is no defined genre of Asian American music. However, through the medium, Asian Americans reconcile an identity, display solidarity with other social movements, and bring the music of their ancestors to the United States.

Stephen Cheng

Stephen Cheng’s career started when he moved to Hawaii from Shanghai, China in 1948. Shortly after raising a family, he moved to New York to attend Columbia and then Juilliard for voice lessons. Cheng is known for his performances on Broadway in The World of Suzie Wong (1958) and Flower Drum Song (1994).

Cheng’s ability to sing in different languages granted him to travel abroad. As he later states in The Tao of voice: a new East-West approach to transforming the singing and speaking voice (1991), Cheng thought music was a way to reach people outside the Chinese community. He was a foreign born Asian-American that used music as a way of communication between racial and ethnic lines. When traveling to the West Indies, he sang in both Mandarin and English. Cheng had mixed rocksteady beat with dramatic Chinese Opera for the Chinese-Jamaican immigrant population. His hit song, Always Together (1967) propelled him back to New York to start a band called the Dragon Seeds. As the 1971 MoMA press release claims, Cheng supposedly formed the group in the “spirit of ‘unity and world peace.’”

The Dragon Seeds, Jazz in the Garden, Museum of Modern Art concert series, 1971

Photograph by Leonardo Le Grand

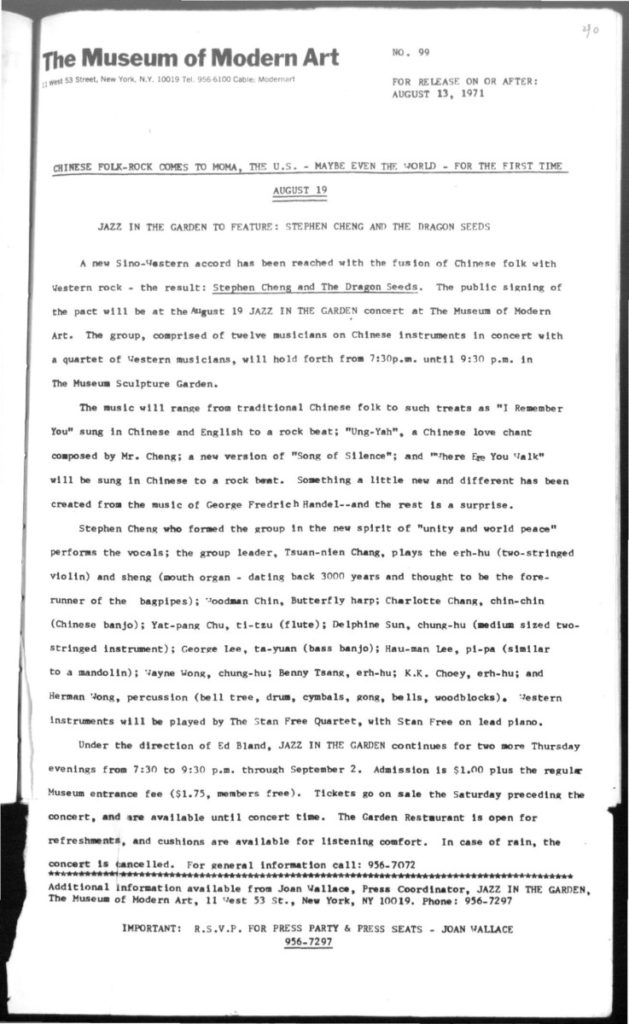

Press Release on Stephen Cheng’s Performance in August 1971 at MoMA

The band was invited to perform at Jazz in the Garden at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. These performances have been running since 1948 to today; reiterations are now called Summergarden. Presenting jazz and classical music, the concert series in the 1970s have highlighted “legends of jazz, blues, and Latin music such as Elvin Jones, Odetta, Big Mama Thornton and Mongo Santamaria.” Cheng and the Dragon Seeds seem to be among the few musicians of the 1970s MoMA performances whose work has yet to be archived extensively. It was not until 2018 that his family was contacted and asked to contribute Cheng’s audio files to the Museum of Chinese in America.

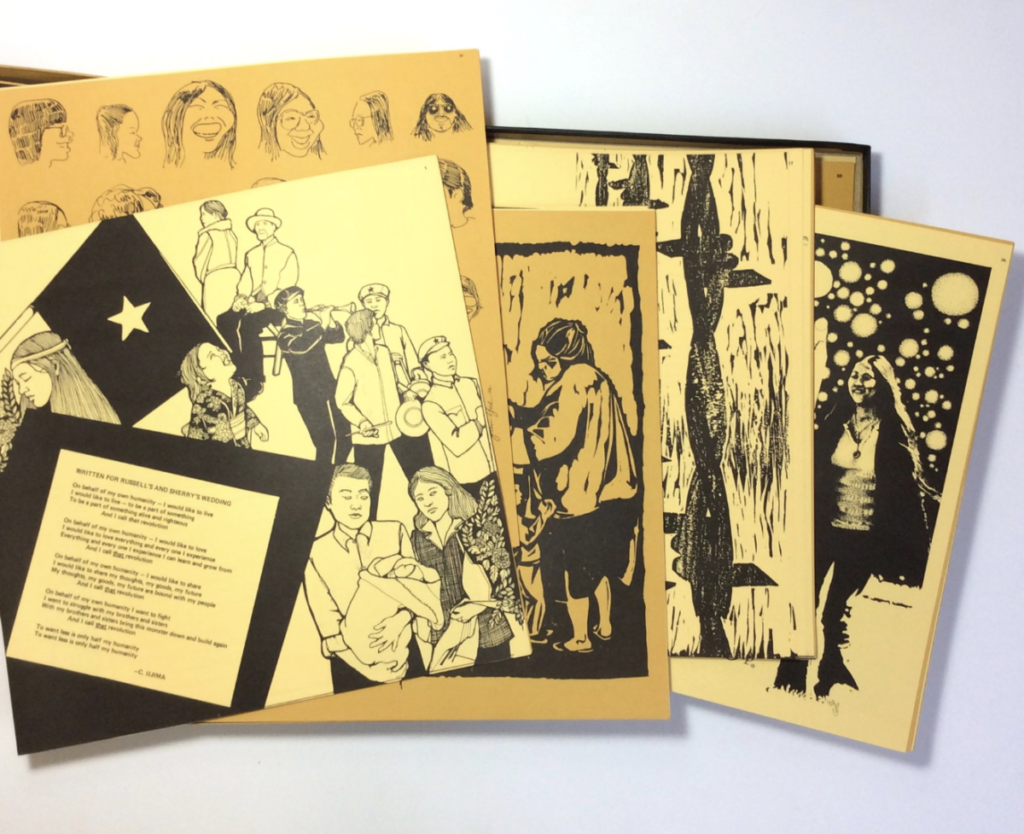

Basement Workshop,

Yellow Pearl, 1972

The Basement Workshop was a political arts organization in New York City active from 1970-1986. In their later years, Basement Workshop turned into an umbrella organization for Asian American arts. They became Asian American Dance Theater, Godzilla Asian American Arts Network, Asian American Arts Centre and Museum of Chinese in America (Asian American Arts Centre and Museum of Chinese in America are still active non-profits both serving in Manhattan Chinatown).

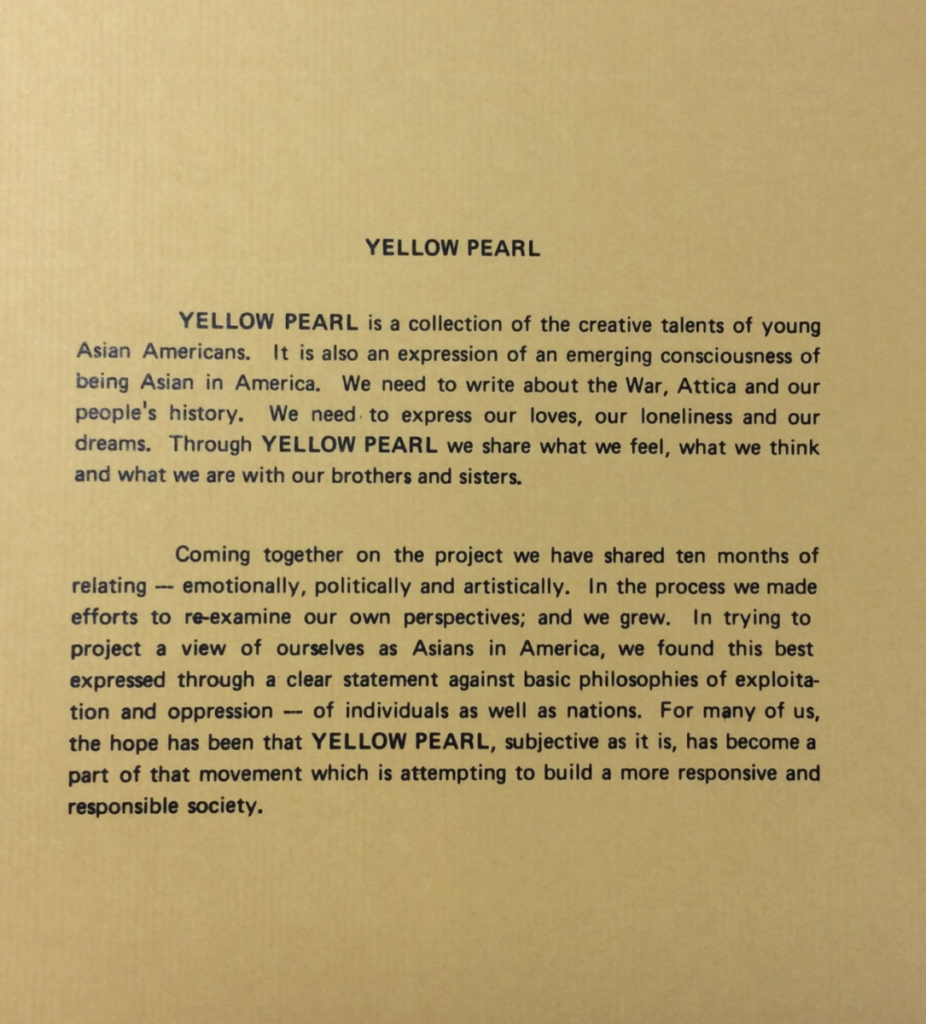

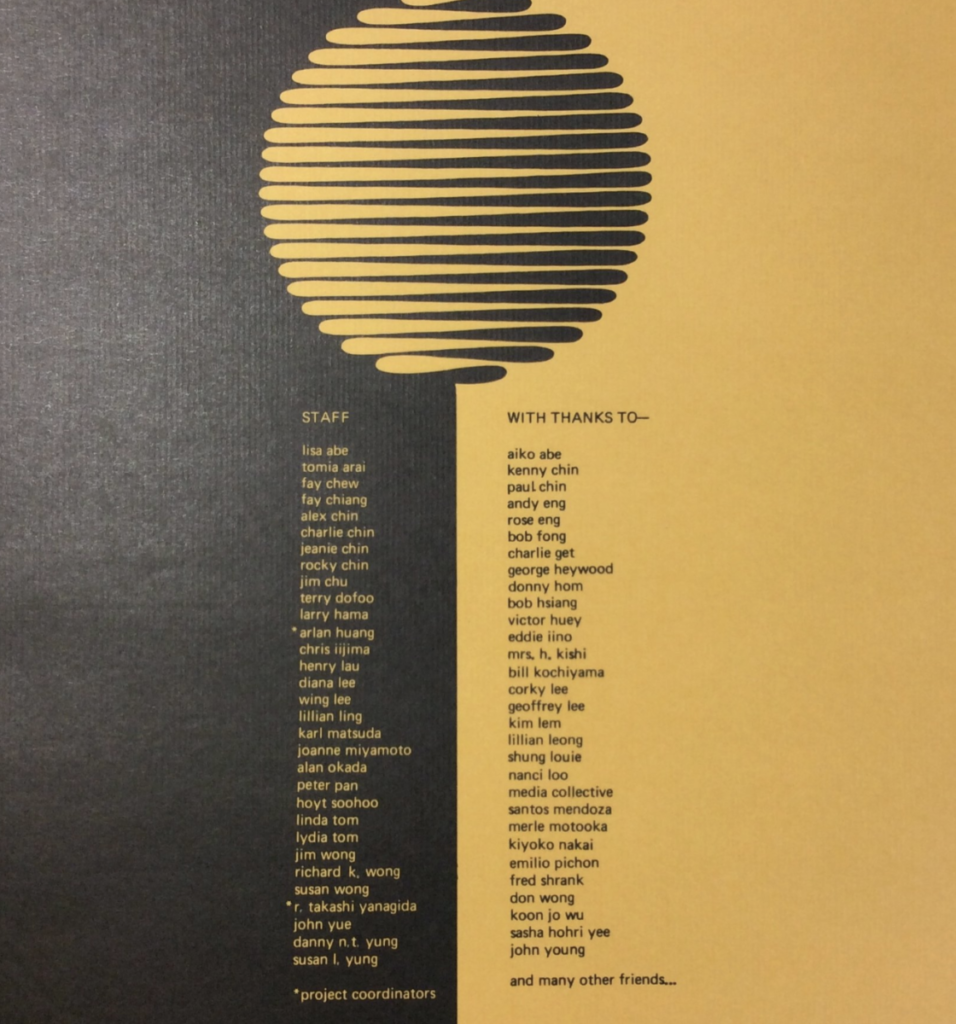

Yellow Pearl is a published arts book that was initially meant to showcase the music of Chris Iijima, Nobuko Miyamoto, and Charlie Chin before the three became the band, Grain of Sand. However, the project grew to encompass writing, art and music by over thirty Asian American artists.

Basement Workshop and Amerasia Creative Arts Program, Yellow Pearl, 1972

Serve the People at Interference Archive, Brooklyn, NY, on Saturday, March 15, 2014. Photograph by Andrew Hinderaker

The portfolio states, “YELLOW PEARL is a collection of the creative talents of young Asian Americans. It is also an expression of an emerging consciousness of being Asian in America. We need to write about the War, Attica and our people’s history. We need to express our loves, our loneliness and our dreams, through YELLOW PEARL we share what we feel, what we think and what we are with our brothers and sisters.” The collection, in most cases, described artists’ feelings towards New York Chinatown and the awareness of their identities as second and third generation Asian Americans. It is important to note that Yellow Pearl mostly defined “Asian American” as American-born Asian, excluding the immigrant generation.

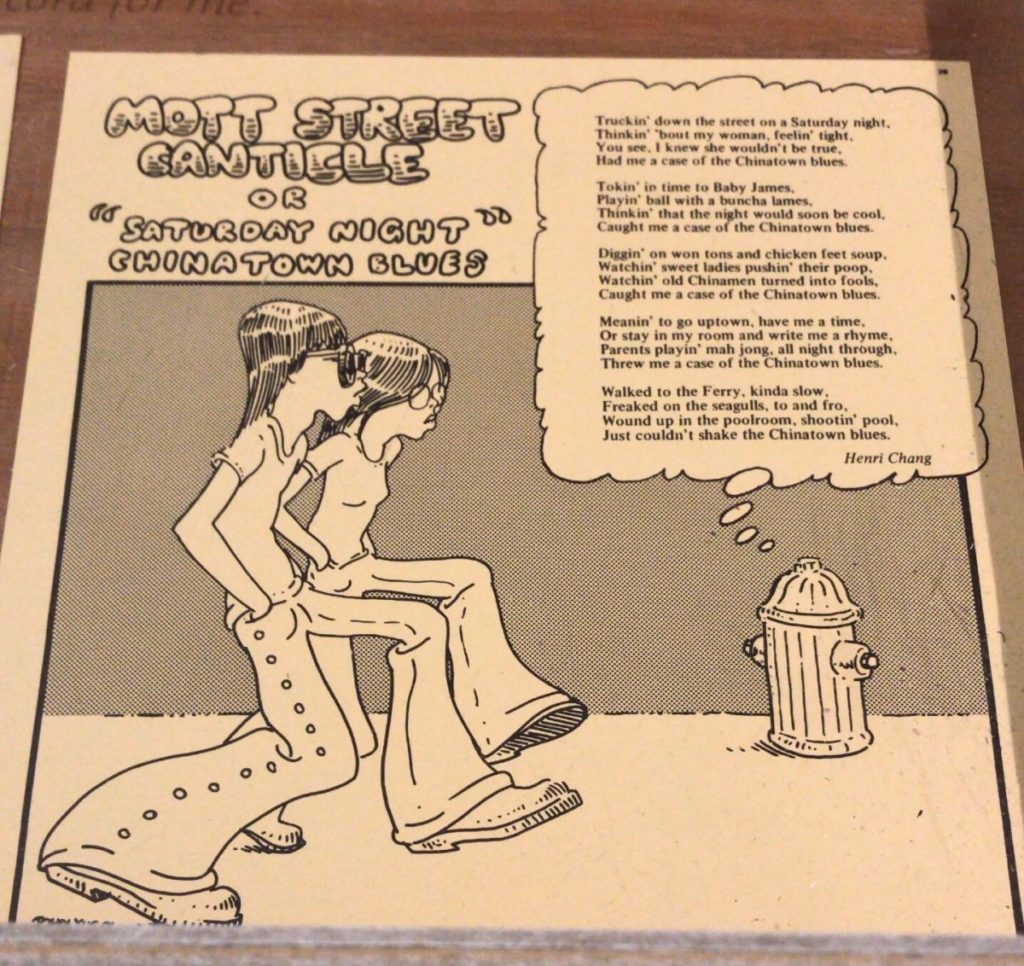

Henri Chang, “Saturday Night” Chinatown Blues

“Diggin’ on won tons and chicken feet soup,

Watchin’ sweet ladies pushin’ their poop,

Watchin’ old Chinamen turned into fools,

Caught me a case of the Chinatown blues.”

Thus, Yellow Pearl served as one of the first culminations of second and third generation Asian American artists. The name intends to reclaim “Yellow Peril,” a term used to describe laborers of Asian descent as the white working class feared job loss in 1870s California. Later, the name Yellow Pearl was reused as a song title in the album, A Grain of Sand: Music for the Struggle by Asians in America.

A Grain of Sand,

We are the Children, 1973

We are the children of the migrant worker

We are the offspring of the concentration camp

Sons and daughters of the railroad builder

Who leave their stamp on America.

Sing a song for ourselves.

What have we got to lose?

Sing a song for ourselves.

We got the right to choose.

We got the right to choose.

We got the right to choose.

We are the children of the Chinese waiter,

Born and raised in the laundry room.

We are the offspring to the Japanese gardener,

Who leave their stamp on America.

…

Foster children of the Pepsi Generation,

Cowboys and Indians — ride, red-man, ride!

Watching war movies with the next door neighbor,

Secretly rooting for the other side.

…

Chris Kando Iijima, Joanne Nobuko Miyamoto, and William Chin are the three artists behind the album, A Grain of Sand: Music for the Struggle of Asians in America. Released the 1973 by Paredon Records, the trio intended to sing songs relating to efforts of the Asian American Movement in the 1970s. Inspired by the Black Panthers and in the style after Peter Seeger’s folk song group, A Grain of Sand directly resisted the marginalization of Asian Americans and expressed their aspirations to politicize their belonging in the United States.

However, their song, We are the Children does not directly address the second generation Asian American experience. Instead, the song describes the American-born Asian’s experiences in relation to the immigrant generation. Iijima, Miyamoto, and Chin claim an identity that cannot be defined without the first-generation. They are the “offspring of the concentration camp” and the “daughters of the railroad builder,” referring to their ancestry and family’s migration to the United States. By claiming such titles, A Grain of Sand attempts to re-contextualize the history of Asian Americans. This history, usually hidden by the self-righteous attitudes towards achieving the “American Dream” and economic stability, is pronounced in this song. The trio of A Grain of Sand represent second generation Asian Americans who attempt to establish their identity as political. They attempt to build solidarity outside of racial lines. As in the song, they lyrics say, “Cowboys and Indians — ride, red-man, ride!/ Watching war movies with the next door neighbor/ Secretly rooting for the other side.” This stanza reinforces an alliance between the colored people living in the United States–in this case, with Native Americans. On the same note, A Grain of Sand performed many of their songs in Spanish, especially because of their associations with many Latinx activists and organizations in New York. Eventually, these relationships resulted in song recordings with the Puerto Rican Movement singers Pepe y Flora.

Fred Ho, the Afro-Asian Music Ensemble & Third World Unity

Afro Asian Music Ensemble performs free concert at Hampshire College 2015.

Fred Ho is a Chinese-American musician, writer, and activist who is known for his work in mixing jazz with Chinese folk music. In his lifetime, he was highly involved in Afro-Asian politics and building the so called “Third World Alliance,” a notion that Black, Latinx, and Asian Americans should band together and fight for the causes of people of color in the United States. Ho identified as a Marxist and his writings often question power: “how is oppression reproduced, and what will take to overturn it? How do social relations under patriarchy and racial capitalism actually shape cultural and artistic production?”

In the 1970s, Fred Ho claimed to have his “identity awakening” as an Asian American through recognizing the struggle of black Americans. At this time, he thought of creating a band and in 1982, he started the Afro Asian Music Ensemble in New York City. The band’s name was inspired by the Bandung Conference, where newly independent countries of Africa, Asia, Central and South America and the Caribbean came together to discuss how the Third World should unite to fight the oppressive powers of the First and Second world. Interestingly, the Bandung Conference did not address the issues of Asians in America. In fact, it was mainly an interaction between Third World Countries, the U.S. itself was not present. However, a few African-American journalists like Richard Wright attended the conference. Whether or not this is false optimism, Ho and Wright claimed to have found a connection to the “colored people of the world.” In Wright’s words, “‘I’m an American Negro; as such, I’ve had a burden of race consciousness. So have these people. I worked in my youth as a common laborer, and I’ve a class consciousness.”

In relation to these Third World Alliance sentiments, many of Fred Ho’s songs are about his political views. Titled very explicitly, most of these songs relate to his anti-capitalist views, Chinese ancestry, and Afro Asian unity. In Wicked Theory, Naked Practice: A Fred Ho Reader, Ho talks about his influences from the Black Arts Movement and he acknowledges the invisibility of Afro Asian unity in schools and media. He says, “The only mass-media image of yellow-black unity today for both APAs and African Americans is probably the Jackie Chan-Chris Tucker collaboration in the Rush Hour movie series…” Though his music is not lyrically based, Ho’s song titles relate to his political ideologies. Ho also reflects on his ancestry. The title, For the Golden Mountain Warrior, evokes Songs from the Gold Mountain anthology of Cantonese folk poems from laborers in San Francisco. This anthology includes poems carved on the wall of cabins on Angel Island where laborers were first kept. Like A Grain of Sand, Ho explicitly refers to the first generation. Fred Ho, in many ways, calls on the American-born Asians to politicize their presence.

Jon Jang, Pledge of Black Asian Allegiance, May 21, 2018

Jon Jang, though based in San Francisco, expresses similar motives as of Fred Ho. In Pledge of Black Asian Allegiance, Jon Jang and Asian Improv Arts commemorate Afro Asian solidarity through the relationship of Yuri Kochiyama and Malcolm X. Kochiyama is known for working with Malcolm X and being present at his assassination. However, she was also a Civil Rights organizer on her own, especially for the Japanese American community.

This 2018 performance has Jon Jang on the piano as well as a spoken word artist. The spoken word artist recites,

“When Malcolm came to Yuri in 1964, she was a tiny woman integrationist but not yet a revolutionary.

Integrate, in-te-grate, assimilate, as-sim-mil-late, all into whiteness…

She was surprised, he shook hands with everyone…”

The poem depicts an Afro Asian solidarity where Kochiyama is supposedly not radical until she meets Malcolm X. They continue with,

“Yuri saw the truth not the lie, she saw the self taught leader who talked about Japanese and Chinese national struggles…

He touched each person…

one by one…

Each survivor of the atomic bomb…of whiteness…

Then Yuri started to see that integration was the gate to whiteness, under whiteness from the center of whiteness…”

It is important to note the varying narratives of Afro Asian unity, especially those surrounding the urge to define Asian American history through African American history.

Chinatown buses to Casinos & Chinese Pop Concerts

Current day, the inter-generational gap between foreign-born Asians and American-born Asians is still readily prevalent. From Cantonese and Peking Opera, foreign born Chinese Americans attempted to resettle their cultural legacies by recreating such entertainment in the U.S. since 1850. Today, charter buses bring the Asian immigrant communities to casinos and cities like Mohegan Sun (CT) and Atlantic City (NJ) respectively, where the first generation can gamble and attend Asian Pop Concerts.

Since the 1970s, Asian Pop artists like Teresa Teng have come to the U.S. to perform, bringing the Chinese immigrant community their pop music. Most of the time, these artists sing both in English and Chinese. Teng was famous for performing The Moon Represents My Heart (1977) as well as Frank Sinatra’s New York New York (1981). Concerts like Teng’s were mostly marketed for Chinese immigrants in the United States; casinos like Mohegan Sun have made websites specifically for their Chinese customers. A Facebook page called “Asian Concerts in USA and Canada” publicizes concerts where Asian singers and actors from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong come to North America. Both charter buses and accommodating websites provide services specifically catered to first generation Asian Americans.

http://chinese.mohegansun.com/home.html

Hong Kong celebrities Roger Kowk and Linda Chung Concert in Atlantic City. Posted by Facebook Page, Asian Concerts in USA and Canada.

These instances reveal the dichotomy in “Asian American” music. Though Iijima, Miyamoto, and Chin of A Grain of Sand are often seen as the creators of the “first Asian American album,” the ways of defining Asian American music have not been established. As Asian American movement was run primarily by second and third generation Asian Americans, the resettlement and assimilationist views of the first generation present at the same time. The contrasting narratives of redefinition by American-born Asians and resettlement by foreign-born Asians reveal the distinct interests between the different generations of Asians in the U.S.