Stop Making Sense: A New Wave of Music

Introduction

The eighties get a bad rap for a lot of things culturally: the fashion, the music, the cheesy Rat-Pack movies. But a lot of people who are quick to label this period of time as tacky fail to recognize the innovations that catapulted the colorful era we remember today.

Politically, the eighties were a time of upheaval and counterculture much like its preceding decades, as young people longed to craft something uniquely their own, something against the tide of the social norm. New wave music is just one of many music genres that grew exponentially in the eighties, and it, in its own way, acts as a rebellion against the masses. New wave did not fit into any specific genre, and it rejected labels as often as possible as it transformed and evolved.

With the changing nature of technology, new wave music focused on experimentation in musical production and the changing sphere of visual production. In an attempt to analyze the impact of new wave music on the eighties and how it represents the culture at the time, I present some key objects pertaining to the American new wave band Talking Heads.

While they technically were formed in the seventies, Talking Heads grew to peak prominence in the eighties. They were a key band in the new wave movement because of their ability to break down barriers in terms of music and explore as many sounds as possible. Some sources that their music has drawn upon include West African polyrhythms and traditional Arabic music from North Africa, in combination with the psychedelic punk and disco funk music genres that were relatively new. David Byrne, the lead singer, was heavily drawn to musical inspiration from other countries while creating songs that dove into topics of politics, death, and love.

Talking Heads’ authenticity and openness in their music has inspired many artists of various backgrounds to this day. The musicians who have drawn inspiration from Talking Heads range from The Weeknd to to Vampire Weekend to Radiohead (whose name comes directly from a Talking Heads song!). The lasting impact of a group who started off with a bunch of lost college students is astounding, and the range that they existed and continue to exist in reflects their talent in innovation.

When MTV Really Meant MTV

MTV was an abbreviation of “Music Television” when it first came onto the scene in the early eighties. It was an ally to new wave music by allowing the transportation of sound through the TVs across households. Especially with the rise of music videos and the appeal of the aesthetic, bands were able to garner an audience through television. There was a “heavy emphasis on visual style,” which fans adored, but in combination “with [the bands’] lack of musical depth,” most of the MTV new wave bands did not last for long.

New wave music, in its lack of genre boundaries, also lacked any sort of political affiliation or movement. It was very apolitical as a music genre, which people either identified with or rejected. The new wave genre was “hopelessly white, middle class, and safe.”

While Talking Heads did not succumb to the tragic fate of many of their one-hit wonder contemporaries, they did share the advantage of MTV and television media in general. Their music video for Burning Down the House, one of their popular singles, often graced MTV. What made Talking Heads successful in comparison to the other passing artists lies in their ability to transform their sound, rather than aiming for commercial success and looks over substance. Talking Heads possessed both visuals and substance, and for this they were able to stay afloat during an uncertain time in the music industry.

Big Suits to Fill

“The actual suit hangs, barely touches your body. It’s got these giant webbed shoulder pads and a webbed girdle that you wear around your waist and pads inside that give you incredibly wide hips and no butt. So when you’re facing sideways you look normal and when you turn to face the front, you’re incredibly wide. Most of the suit isn’t even touching you; it’s just hanging from this scaffolding.” – David Byrne

3:00 – 3:45

David Byrne is the lead singer of Talking Heads, and during their concert film Stop Making Sense (1984), he wore a massive grey suit that would later become a huge part of his and his band’s identity. The suit was designed by Gail Blacker and she described it as “more of an architectural project than a clothing project.” There are various reasons given by Byrne himself as to why he designed this ridiculously sized suit. During a well-known interview for Stop Making Sense, in which Byrne dons a bunch of disguises to interview himself, he says that he constructed the suit because he “wanted [his] head to appear smaller and the easiest way to do that was to make [his] body bigger.” It did exactly what he wanted and more. Its dependence on its wearer allowed every movement and motion to be emphasized to a comedic effect. And with David Byrne as its wearer, the suit had more than enough dance moves to work with.

Looking back at artists that got their start in the 50s and 60s, such as the Temptations or the Beatles, it’s quite common to find them wearing formal suits when they perform on TV. This brings in the rules of respectability and professionalism of the time, and how dressing uniformly cultivated a brand image. However, with time, more and more artists broke free of the physical and cultural constructiveness of formalwear. Byrne took this idea and applied it in Postmodernist fashion. Postmodernism was part of a movement that contradicted and questioned the “artistic norms” established long ago. It often calls upon irony and satire to develop its message, and Byrne, taking an outfit that once constricted the artist and using it to actually show off the extent of his movements and dances falls right under the category of Postmodernism.

Postmodernist Production

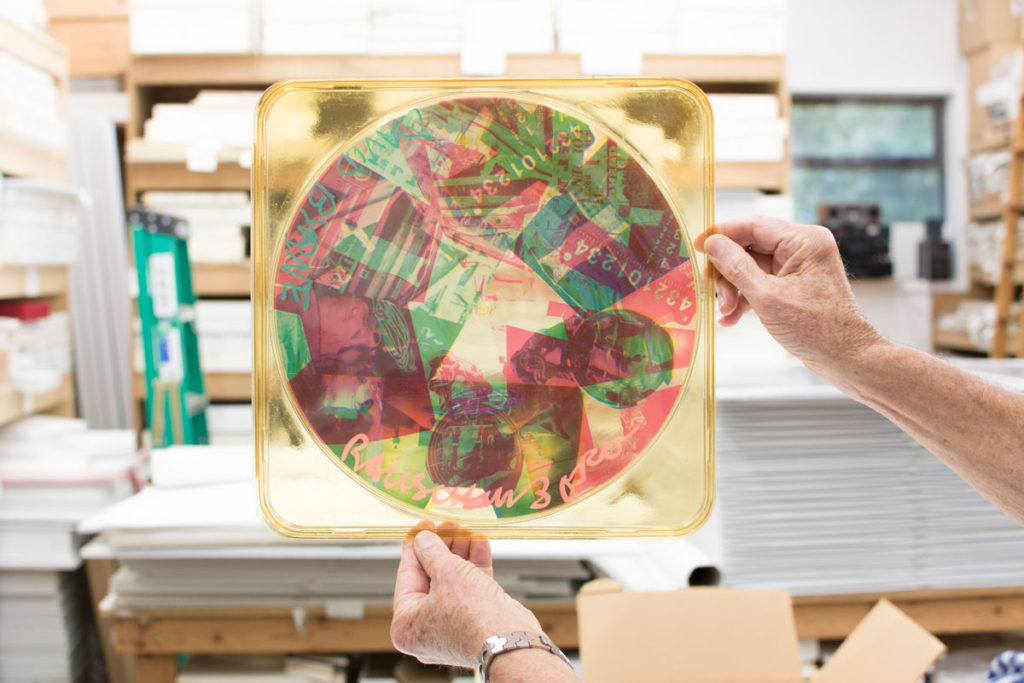

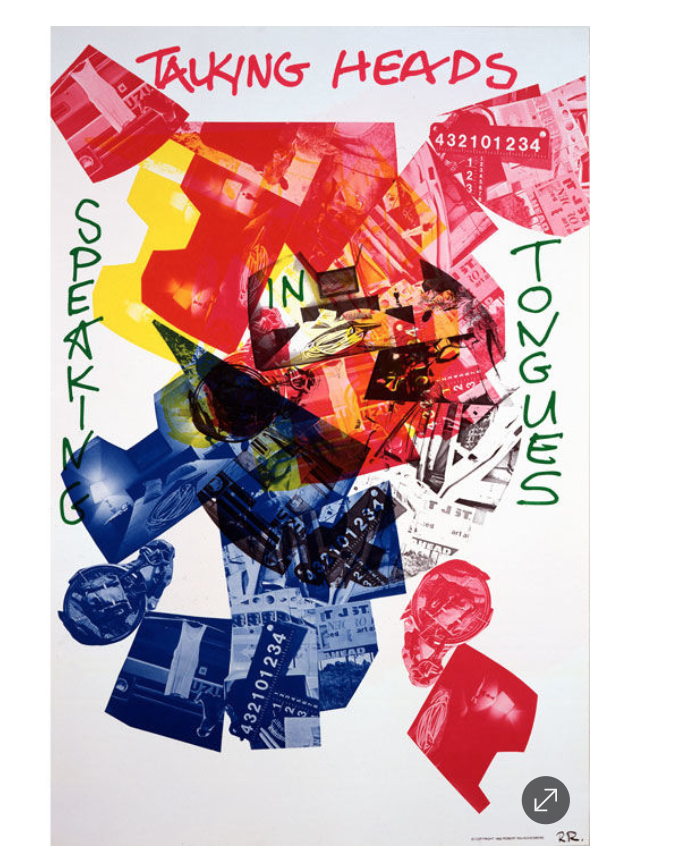

The Postmodernism movement intertwines itself with Talking Heads in more ways than one. David Byrne collaborated with Robert Rauschenberg, a prominent artist of the movement, who is said to have inspired John Cage’s 4’33” (1952), on art for the band. Rauschenberg agreed to help the band design the art of their fifth album, Speaking in Tongues. The art itself was actually inspired by sculptures that Rauschenberg had previously created from a series titled Revolver. The sculptures boasted bright colors and silkscreen prints. There were five circular Plexiglass discs that would rotate at the control of the viewer, changing its composition with each viewing.

Robert Rauschenberg and David Byrne

Revolver II, inspiration for the album art

Poster of the album art

The album art showcased Rauschenberg’s signature style of layering images, creating a collision of seemingly random objects. What proved most challenging was transferring this art to the vinyl medium. Reportedly, Jerry Harrison, guitarist and keyboardist of Talking Heads, struggled to find someone who could essentially transfer the art onto a clear vinyl LP. The difficulty in production led this particular vinyl design to be sold as “limited edition” with only 50,000 made. The record sold for $12.98 at the time, and 1,000 “deluxe editions” which were signed by both Byrne and Rauschenberg were sold for $100 through art galleries. Artist and friend Andy Warhol actually purchased an album in 1983. The interconnectedness of the art world was especially prevalent in the Postmodernism Movement, as many artists collaborated and worked with their contemporaries, sharing ideas and inspirations. This particular album art also shows how important visual aesthetics were to Talking Heads. Obviously, most artists like to convey a cohesive aesthetic in their work, but the visual experience of their listeners was almost as important as the musical experience to the band.

Qu’est-ce que c’est?

Created by Ikutaro Kakehashi, the Roland TR-808 drum machine came out in 1980 and was only manufactured until 1983. Despite this short window, it has made and continues to make a huge impact on music and pop culture. This machine was one of the first to simulate the sounds of the drum instrument. Many critics saw the machine as too artificial in its sound, and disparaged its abilities in the music industry. However, many artists saw this as something revolutionary, something accessible and customizable. One of these artists was Byrne, and in Stop Making Sense, the opening performance of “Psycho Killer” utilizes the drum machine, interplaying electronic drum beats with Byrne’s robotic, gawky dance moves.

The TR-808 is important in symbolizing the changing atmosphere of music production at the time, with more and more technological advancements allowing for more and more experimentation. Eighties music is usually thought of in an upbeat tempo, with an excessive use of synthesizers, and catchy but repetitive melodies. It also highlights something often discussed with the historical impact of new wave music and Talking Heads: whiteness. The demographics of new wave artists and fans were dominated by white people, usually male. As previously stated, new wave music relied on artificial instruments and it embraced the growing technological landscape at the time. With all the discussions of what’s “real” and “authentic” in terms of music, new wave artists often translated the artificiality of their music into their personas. New wave music was all about experimentation, and a lot of new wave artists experimented with themes of humanness. Artists like Devo, Tears for Fears, and Depeche Mode exhibited a sort of “nervousness” and mechanization in their music and movements. This robotic theme contrasted greatly with the “natural” expression that cultivated in rock and blues music, shown both through the movement of blues music and the unbuttoned shirts and long hair that most rock stars donned at the time. Through abstractions involving deep discussions of Freudian psychology and human nature, the robotic persona became associated with whiteness. The white middle class of the 70s and 80s was seen as uptight, high strung, and the “loose” music that surrounded them was seen as a counterculture, a rebellion against these societal norms. Byrne took this identity and shows through his jerky, unnatural dance moves how he chooses to break free from the consciousness of expression and motion that constricted people at the time. In new wave’s rejection of the uninhibited freedom associated with the more diverse genres of blues and rock music, it finds its own freedom by embracing its identity and awkwardness.

This Must Be The Place

But I guess I’m already there

I come home, she lifted up her wings

I guess that this must be the place

I can’t tell one from the other

Did I find you or you find me?

There was a time before we were born

If someone asks, this is where I’ll be, where I’ll be…”

“For a band rarely given to addressing issues of the heart head-on, ‘Naive Melody’ remains an unexpected and peerless achievement.” -Winston Cook-Wilson in a Pitchfork list of the best songs of the 1980s

“In a lot of the songs David’s lyrics didn’t have any personal significance for him. They were from things he heard or read. But in this case it sounded as though he really meant it.” – Chris Frantz, drummer of Talking Heads

“This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody)” is one of Talking Heads’ most popular songs…today. Upon its release, it was not disliked, but it was definitely overlooked by critics at the time in regards to production and content. In a 1983 Rolling Stone review of the track’s album, Speaking in Tongues, an album described as one that “finally obliterate[d] the thin line separating arty white pop music and deep black funk,” “This Must Be the Place” is never mentioned or acknowledged as a memorable track.

This is surprising because out of all Talking Heads songs, this would seem to resonate most with people because it was their only love song. Most of their other songs consisted of fictional storylines, made up narratives from the mind of Byrne. “Psycho Killer” is written from the viewpoint of a fictional serial killer, their popular hit “Burning Down the House” follows no narrative but offers vivid imagery, and so on. There were songs featuring “ironic faux-sincerity” and “songs about buildings and food,” but there lacked a category of song that pervades through all genres. Then came “This Must Be the Place,” which describes how someone can feel like home, a common trope in love songs and stories, and something very human that Byrne himself acknowledges he previously avoided due to his shy and private nature.

The (Naive Melody) part of the title stems from the literal melody of the song. The bassline and guitar part keeps a steady G-A-B-A chord progression for the duration of the song. During commentary of the concert film Stop Making Sense, Byrne stated that a lot of professional musicians would not play a song as simple and repetitive as this, and that is what makes the music “naive.” It is interesting that both the melody and the meaning of this song is so simple, yet it was not as critically-acclaimed as other, more experimental songs of the band. Perhaps its simplicity made it fall short in the eyes of critics, but to the general public, this song has remained a classic love song.

Works Cited

Anderson, Pete. “Making Sense of David Byrne’s Big Suit.” Put This On, 20 Dec. 2017, putthison.com/making-sense-of-david-byrnes-big-suit-the-tom/.

Cain, Abigail. “The Story behind Robert Rauschenberg’s Iconic Talking

Heads Album Cover.” Artsy, 18 Aug. 2016, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-the-story-behind-robert-rauschenberg-s-iconic-talking-heads-album-cover.

Cateforis, Theo. Are We Not New Wave? : Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s. University of Michigan Press, 2011.

Cateforis, Theo. “Performing the Avant-Garde Groove: Devo and the Whiteness of the New Wave.” American Music, vol. 22, no. 4, 2004, pp. 564–588. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3592993.

Cohen, Scott, and Glenn O’Brien. “Talking Heads: Our 1985 Cover Story.” Spin, 21 July 2019, www.spin.com/featured/talking-heads-david-byrne-june-1985-cover-story/.

Frances, Elle. “DAVID BYRNE’S ‘BIG SUIT’: POSTMODERNISM, POWER AND PROFESSIONALISM.” DAVID BYRNE’S “BIG SUIT”: POSTMODERNISM, POWER AND PROFESSIONALISM, 1 Jan. 1970, ellefrances.blogspot.com/2014/02/david-byrnes-big-suit-postmodernism.html.

Fricke, David. “Speaking In Tongues.” Rolling Stone, 25 June 2018, www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/speaking-in-tongues-188876/.

History.com Editors. “The 1980s.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 23 Aug. 2018, www.history.com/topics/1980s/1980s.

Murray, Noel. “‘This Must Be The Place’ Was David Byrne’s First Love Song.” Music, Music, 23 Aug. 2017, music.avclub.com/this-must-be-the-place-was-david-byrne-s-first-love-s-1798243973.

“New Wave Music.” St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, Encyclopedia.com, 10 Dec. 2019, www.encyclopedia.com/media/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/new-wave-music.

Songfacts. “This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody) by Talking Heads – Songfacts.” Song Meanings at Songfacts, www.songfacts.com/facts/talking-heads/this-must-be-the-place-naive-melody.

“This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 12 Dec. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/This_Must_Be_the_Place_(Naive_Melody).

Verini, James. “The Talking Heads Song That Explains Talking Heads.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 19 June 2017, www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-talking-heads-song-that-explains-talking-heads.

Wolff, Daniel. “Same as It Ever Was.” Grand Street, vol. 6, no. 3, 1987, pp. 175–183. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25006997.