Kyle Painting

Race records- sound recordings of the early 20th century that were made exclusively by and for African Americans -Encyclopedia Britannica 1

The race record industry has always served as a focal point for debate among many scholars and historians alike. On one hand, race records provided a new platform for black artistic expression in America, allowing many new black genres to spread far beyond the confines of the rural south and a few Northern clubs, into the homes of Americans all over. This new booming industry paved the way for black music to become a staple of American popular music. However, race records also had a negative impact in the sense that they solidified, for some time, stereotypes of what black music should sound like. This duality of race records as both beneficial and harmful to black progress makes it difficult to reach a consensus about whether the ultimate impact that they had was for the better or for the worse.

Sophie Tucker and Early Representations of Black Music

Prior to the invention of the phonograph by Thomas Edison’s corporation in 1877, vaudeville and minstrelsy dominated the white American impression of what was considered to be musical blackness (Miller, Pg.1). During the late 1800s and early 1900s, many touring minstrel shows attempted to establish stereotypes of African American mannerisms, dialects, and sounds. When the newly established recording industry began to thrive, prejudices of the time lead to the exclusion of most blacks from the recording studio. Instead, white performers perpetuated earlier minstrel tropes through the creation of recorded coon songs, tunes which were marketed as being dead-on representations of black sounds and dialects. Marion Harris and Sophie Tucker were two especially famous white singers of the day who recorded these types of songs, along with ragtime, blues, and jazz renditions. These singers actively tried to uphold a sense of white perceived cultural accuracy regarding their music by claiming that they had been coached by black musicians (Brackett, pg. 79).

Here we see Sophie Tucker posing in blackface, as she would have appeared on stage for her minstrel acts. Although it is difficult to tell from the black and white photograph, the Ukrainian-born singer has covered herself in either burnt cork or shoe polish to assume the roll of a black female, complete with a stereotypical wig and dress of the time. In her touring minstrel shows, she would perform in this costume to white audiences. While she was on stage she would sing, dance, and talk in a way that was considered to be black, but in reality was a horrible comedic trope intended to make the audience laugh at the supposed behaviors and linguistic differences of blacks.

The Beginnings of Black Recording

RCA Victor began to introduce black artists to the recording studio in 1914, enlisting black composer James Reese Europe to direct the Castle House Orchestra in recording an album. RCA was not ready to admit to working with black artist just yet, leaving Europe’s name out of every advertisement for the record. Soon after, due to falling behind the competition, Columbia records began to actively recruit black performers. While they had previously worked with Bert Williams for over a decade, and Carroll Clark in the early ‘teens, Columbia now began to incorporate blues artist W.C. Handy, and ragtime/jazz artist Wilbur Sweatman. The main distinction between these early endeavors of record companies, when compared to later endeavors, is that the record companies only pursued working with black artists that they thought would sell well to white audiences (Sutton, pg.vii-viii). Consequently, much of the recording process was directed by white executives, who skewed the end product toward white taste. In order to overcome white musical direction and filtration within the recording industry, several key players would emerge within the black community who would attempt to provide recording platforms for their own people.

Contrary to popular belief, Harry Pace’s Black Swan Records was not the first label created and owned by an African American. In 1919, George W. Broome created the Broome Special Phonograph company, which specialized in recording black concert artists. Broome advertised in Crisis magazine, taking an all new approach of marketing to a solely African American audience. Broome’s first release was a recording of Harry T. Burleigh singing “Go Down Moses.” Broome went on to record artists such as R. Nathaniel Dett, Clarence Cameron White, Edward H. Boatner, and Florence Cole-Talbert (Sutton, pg.1-4). In the image above, we see a pressed recording of “Villanelle” by Florence Cole Talbert, one of the most prolific black sopranos of the early 20th century. The significance of this record, along with others commissioned and sold by George W. Broome’s label, is that everything, from the creation process to the marketing material, was directed entirely by blacks. When considering that these records were intended for a black audience, it becomes obvious that Broome had pioneered the first race record business.

Mamie Smith: Crazy Blues

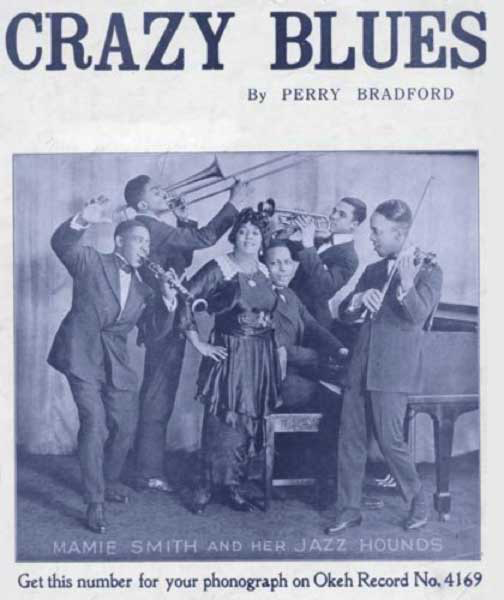

In February of 1920, Perry Bradford, a Vaudevillian and pianist from Alabama, succeeded in convincing Fred Hager, recording manager at Okeh Records, to meet with him about having Mamie Smith sing his music on record. During this meeting, Bradford sold Hager on the idea of creating a blues record, sung by a black female, and marketed to blacks and whites alike. Shortly after a deal was struck between the two of them, Bradford brought Mamie Smith into the Okeh studio to record his songs “That Thing Called Love” and “You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down.” Accompanying her was the Rega Orchestra, an all-white studio band, which was marketed as being all-black.

The release did well enough to convince Hager to take another chance with Smith, and in August later that year, Smith recorded “Crazy Blues”. This time Bradford made sure to enlist the help of the Jazz Hounds, an all-black studio band, to accompany Smith in the recordings. Contrary to Mamie’s first record with Okeh, “Crazy Blues” was a smashing success. Estimates place sales within the first year within the ball park of a million copies, which was enough to alert industry executives all over (Horton, pg.16). In the wake of “Crazy Blues”, Columbia Records signed Edith Wilson and Mary Stafford, hoping to cash in on the coming blues craze. Edison and RCA Victor were hesitant to join in, and remained observant parties.

Lyrics sample: Crazy Blues

“Now I can read his letters

I sure can’t read his mind

I thought he’s lovin’ me

He’s leavin’ all the time

Now I see my poor love was blind

Now I got the crazy blues

Since my baby went away

I ain’t got no time to lose

I must find him today”

Crazy Blues quickly brought the entire genre of blues to the forefront of American pop culture, creating an opening for black female artists to join the ranks of the most successful musicians around. However, Crazy Blues set a precedent for these artists to stay within the boundaries of blues. Lyrics focused on sorrow and on good for nothing men ingrained negative images of black men in the minds of Americans, which would continue to be perpetuated as the blues craze was capitalized upon.

Beginning of The Race Record Boom

The advent of the blues craze was seen a beacon of hope for many black musicians. The Chicago Defenderissued articles discussing the promise of this burgeoning popular genre. All was not positive however, as Okeh’s marketing ploys to white audiences often featured minstrel characters with exaggerated features and comedic lines.

. Okeh Phonograph Corporation, to 1930, 1930. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200049069/.

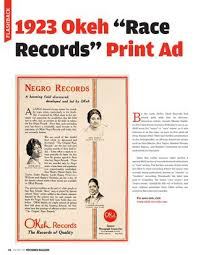

Mamie Smith’s music had become a driving force behind a new popular genre of blues, one that didn’t resemble its folk origins, one that became increasingly influenced by white record company executives. In 1921, Okeh created a new 8000 series catalogue featuring solely black artists. Labeled as the “Colored Catalogue”, Okeh hoped this new series would be able to capitalize from their new black audience.

This catalogue was not market to black and white audiences, as Mamie Smith’s records had been before, rather it was focused solely on the black consumer. A year later Okeh changed the name of the 8000 series to “Race Records,” thus the term that would ignite an entire industry was born (Sutton, pg.30-31). The Image above is an ad of one of Okeh’s early race records.

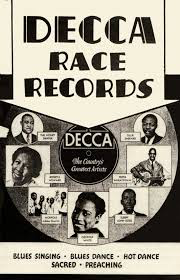

Race Record Boom

In the wake of Okeh’s race record success, many record companies were interested in the idea of releasing their own race records. Many talent agents, such as Joe Davis, saw an opportunity to package blues singers and sell them to eager white-owned record companies that had no idea how to produce race records of their own. Davis came to manage a slew of vaudeville-blues singers and accompanists, who he readily packed into whatever combination suited each record company’s taste. Pathe, Vocalion, and Brunswick readily shelled out cash in order to capitalize on the growing race record trend.

A new industry player in the form of Ajax Records came to the attention of Davis, who, given his recent failure to market to Victor and Edison, was ready to secure a new slew of deals. Ajax was the brainchild of Herbert Berliner, who formed the record company to market race records almost exclusively. Together, Herbert Berliner and Davis put together a series of race records that reached a whole new level of commercial success. Eventually the larger record labels gave-in, and established their own race record catalogs (Sutton, pg.70-77,84-87).

Expansion

Soon the race record industry expanded to incorporate new kinds of recordings focused on black Americans. During the mid 1920s, Columbia, Okeh, Victor, and Paramount all began to release race records featuring religious songs and sermons by African American pastors. In 1925, Reverend Calvin P. Dixon recorded a sermon with Columbia records, becoming the first to do so on a major race record. While Dixon’s recordings didn’t receive much commercial success, they set the stage for more religious recordings by the likes of Reverend A.W. Nix, Leora Ross, and J.C. Burnett, whose records went on to sell extremely well (Walton, pg.207-208).

These religious records went on for decades, as evidenced by the prolific career of Reverend James M. Gates, who recorded over 220 sermons during his lifetime (Martin, pg. 15).