Baez and Dylan – Two Different Voices for Change

The Civil Rights movement of the 20th century was a period of struggle for political and social equality for African Americans. During this time, both Black and White Americans struggled against state and local laws that enforced racial segregation, the mistreatment of African Americans by the legal system, and the gratuitous violence that African-Americans suffered from. Six pivotal moments within this period were the passage of Brown v. Board in 1944, Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus in 1955, the Civil Rights Act of 1957, Woolworth’s Lunch Counter sit-ins in 1960, Freedom Riders who rode buses into segregated southern areas in 1961, and the March on Washington in 1963. [1]

For this project, I’m going to focus on how two of the most well-known folk musicians of the 20th century – Bob Dylan and Joan Baez – participated in this movement through writing and performance. Both had illustrious careers that spanned decades. Baez released 25 studio albums, 15 live albums, and 35 singles [2], while Dylan performed hundreds of times, releasing 38 studio albums in total and receiving numerous awards, including nine Grammys and the Nobel prize for in literature in 2016 [3]. However, the two engaged in political activism very differently. While Baez refused to salute the American flag when she was fifteen, traveled to Vietnam with a peace delegation in 1972, and learned phonetic Czech to introduce Vaclav Havel on TV in 1989, Dylan’s “devotion to radical causes didn’t last more than the proverbial five minutes [4].” Still, his albums The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1973) and The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964) became hallmarks of the Civil Rights Era, and the beginning of his career will always be inextricably be linked to both Baez and the Civil Rights movement. (The two casually dated for a few years [5]; when Dylan’s tour manager eventually asked him why he married Sara Lownds and not Baez, he answered “Because Sara will be there when I want her to be home, she’ll be there when I want her to be there, she’ll do it when I want to do it. Joan won’t be there when I want her. She won’t do it when I want to do it.” [6])

There is much, much more scholarship on Dylan than Baez, despite the fact that Baez played a major role in the Civil Rights movement and activist causes more broadly. A search through Emory’s library only yields seven books about Baez but over a hundred on Dylan. Baez’ contributions to the Civil Rights movement and her beautiful voice shouldn’t be overshadowed by Dylan’s legacy, and I hope that within the following project I am able to write about both artists in a balanced way.

In 1963, Baez opened March on Washington with her rendition of “We shall Overcome,” a protest song that was used for political purposes in a strike against the American Tobacco Co. and subsequently by Pete Seeger, Guy Carawan, and the “Freedom Singers” organized under the SNCC [7]. The March was a historic moment in American history; it was both the venue for MLK’s “I have a dream” speech, what would become “one of the most famous orations of the civil rights movement, and of human history,” as well as the catalyst for The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and The Voting Rights Act of 1965 [8,9]. In her autobiography, Baez describes the performance: “In the blistering sun, facing the original rainbow coalition, I led 350,000 people in “We Shall Overcome,” and I was near my beloved Dr. King when he put aside his prepared speech and let the breath of God thunder through him, and up over my head I saw freedom, and all around me I heard it ring [10].”

It is striking to me that in the article I referenced above ([7]), which details the use of the song in America throughout the 20th century, Baez isn’t even mentioned. Again, I think the significance of her contributions to the Civil Rights movement has likely been undervalued in scholarly analyses. Below is a video of her chilling, powerful performance, and a copy of the transcript of the authorized recording of the event.

Transcript of the Authorized recording of The March On Washington: We Shall Overcome

Dylan also performed at the March on Washington, singing “Only A Pawn in Their Game”). Only a Pawn in their game is a tribute song to Medgar Evers, a prominent civil rights activist who was killed in June of 1963 and was posthumously awarded the Spigarn medal by the NAACP [11]. In the song, Dylan doesn’t just criticize Evers’ killer, he also criticizes the “Southern politician who preaches to the poor white man ‘you got more than the blacks, don’t complain'” and “uses the Negro’s name (…) for gain.” Princeton historian Sean Wilentz characterizes the song as “not falling into the moral dramaturgy of the civil rights movement (…); (digging) a little deeper and making people think a little bit more [12].” I personally don’t agree with Wilentz’s characterization of (the conceptualization of) “righteous civil rights workers — black and white — against an obdurate segregationist system,” as “moral dramaturgy,” and I am skeptical of the presumption that Dylan’s lyrics about politicians engendering racial tension at the expense of both African Americans and poor whites substantively changed the narrative. Still, it is worth noting Wilentz’s response (which was published on the fiftieth anniversary of the March).

Lyrics from “Only A Pawn in Their Game”:

A bullet from the back of a bush

Took Medgar Evers’ blood

A finger fired the trigger to his name

A handle hid out in the dark

A hand set the spark

Two eyes took the aim (…)

A South politician preaches to the poor white man

“You got more than the blacks, don’t complain

You’re better than them, you been born with white skin, ” they explain

And the Negro’s name

Is used, it is plain

For the politician’s gain

As he rises to fame

And the poor white remains

On the caboose of the train

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their game

Dylan and Baez didn’t only perform alone – they also performed together, singing “When the Ship Comes in.” (Dylan allegedly penned the song when a hotel clerk denied him admission because of his disheveled looks) [13]. Below is the video recording of the event. Notice how Dylan doesn’t give a word of introduction before breaking into song, and neither does Baez, who quietly jumps in, joining him for a second verse. Dylan had very obviously positioned himself as a civil rights advocate before this moment, hence why “no introduction was needed.” Still, it seems like Dylan might have said at least a few words. His failure to do so might be attributed to his general shyness, to his eccentricity, or to his pretentiousness; in my combination, it was probably a combination of all three. (I will examine these assertions below).

It is also interesting to consider what Baez’s quiet entry into the song says about her self-positioning within the civil rights movement more broadly. Though she was a stalwart advocate for various social movements throughout the twentieth century, Baez is unassuming, humble, and almost demure – a stark contrast to Dylan [14]. In her autobiography And A Voice to Sing With, she talks about Dylan with sentimental remorse – she saw him as simultaneously brilliant and apathetic, a genius who would “go down forever in the history books as a leader of dissent and social change, whether he liked it or not [10].” Baez herself undoubtedly deserves the title she assumes (rightfully so) that the world will give Dylan.

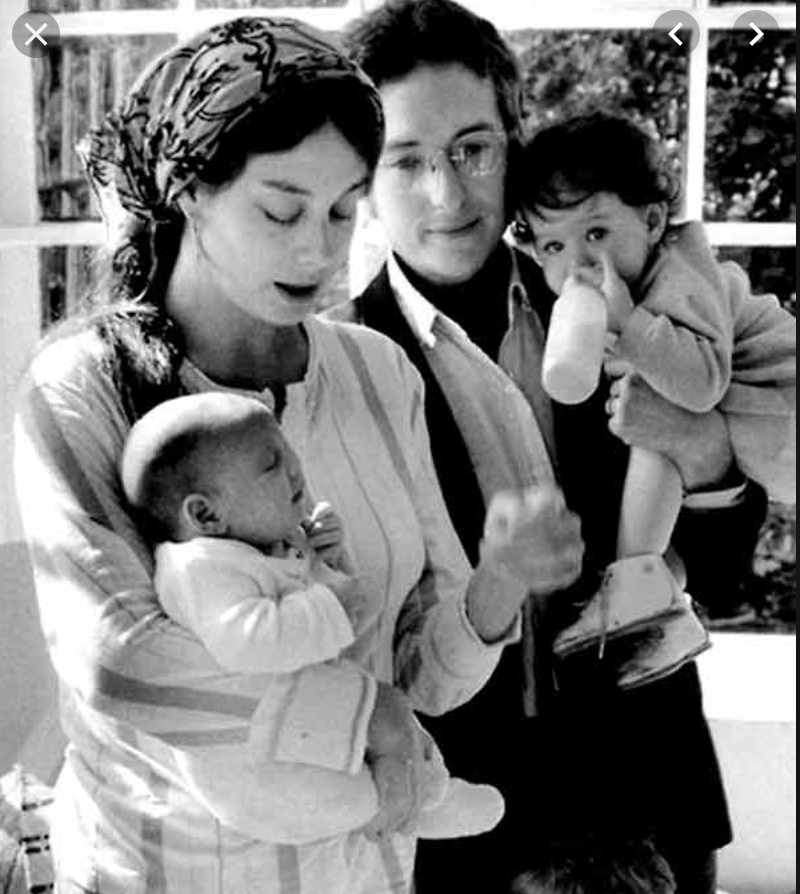

Baez and Dylan, March on Washington

Dylan’s persona:

In the following press conference from 1965, Dylan stares in an almost hostile way at the interviewers and the fans in the room; his expression is broken only by his almost imperceptible smiles at his own jokes. When one interviewer asks him how his “folk-rock” is coming along, Dylan stops him and says “I don’t play folk-rock (…) I like to think of it more in terms of vision music, mathematical music.”

The moment (~3:19) is unquestionably hilarious – why no one in the audience bursts into laughter at Dylan’s nonsensical, unabashed statement is beyond me. It certainly says something about how others generally perceive him. Beyond its comic value, the encounter is important still for a different purpose – at the moment when Dylan is given the opportunity to define his music and his brand, he defers, only really offering “the words are just as important as the music; without the music, there would be no words.”

Dylan’s remarks might be odd, but they are somewhat unsurprising. Dylan was a remarkably uppity, eccentric, and bold character, and this is evident from Baez’s autobiography. In the autobiography, she describes numerous events that seem ludicrous: Bob telling her that she could keep his wife’s blue nightgown, him staring at a girl from across a restaurant so “imploringly” that she ended up at a table with Baez, her sister, and her sister’s husband, and him directing an acting scene with Sara (his wife), Baez, and himself “in a creative frenzy.[10]”

Prior to march on Washington, Dylan had performed benefits with the SNCC, or Student Nonviolent coordinating committee, which organized itself around the principle of ‘radical, nonviolent confrontation of white supremacy.'[15] Furthermore, he sang “Blowin in the Wind” at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival [16]. However, his foray into politics didn’t last long, and he quickly became disenchanted with his position within the Civil Rights movement. He “felt co-opted by white movement leaders,” and shoved into a role that he was reluctant to play [15]. At some point, he remarked ‘I wasn’t going to fall for any kind of being a leader,’ and ‘Don’t follow leaders watch your parking meters.'[16] In 1963, he gave an infamous speech after receiving the Tom Paine award by the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee [15]

Text from Paine Speech: “And they talk about Negroes, and they talk about black and white. And they talk about colors of red and blue and yellow. Man, I just don’t see any colors at all when I look out. I don’t see any colors at all and if people have taught through the years to look at colors – I’ve read history books, I’ve never seen one history book that tells how anybody feels. I’ve found facts about our history, I’ve found out what people know about what goes on but I never found anything about anybody feels about anything happens. It’s all just plain facts. And it don’t help me one little bit to look back.

I want to accept this award, the Tom Paine Award, from the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee. I want to accept it in my name but I’m not really accepting it in my name and I’m not accepting it in any kind of group’s name, any Negro group or any other kind of group. There are Negroes – I was on the march on Washington up on the platform and I looked around at all the Negroes there and I didn’t see any Negroes that looked like none of my friends. My friends don’t wear suits. My friends don’t have to wear suits. My friends don’t have to wear any kind of thing to prove that they’re respectable Negroes. My friends are my friends, and they’re kind, gentle people if they’re my friends. And I’m not going to try to push nothing over.

The speech alienated much of the audience, and by 1964, Dylan had largely stepped out of activism.

While Bob Dylan’s political involvement waned, Joan Baez’s never faltered. Here, in 1966, she is pictured as the only woman in a crowd of African-American men and children that includes MLK himself; the group is leading a group of children to their newly integrated school in Granada. Her position is poignant – while she is in the center of the photograph, she’s not leading the group, holding a sign, or otherwise making herself the center of attention. Her quiet presence is a metaphor for her perpetuity in “social and political matters throughout the years” – unlike Dylan, her activism didn’t burn and fizzle out, and throughout the decades she continued to “lend her voice to many concerns for a variety of causes [17].

In 1987, Joan Baez published her autobiography called A Voice to Sing With. Within the autobiography, she details her initiation into the Civil Rights movement, saying “In 61′ I was barely aware of the Civil Rights movement (…) I did discover, however, that no blacks were allowed at any of my concerts, and would not have been allowed in if they had come.[10]” Subsequently, she details how she won over a Black audience in Birmingham with her rendition of “Let Us Break Bread Together on Our Knees.” In an earlier paragraph, she describes her performance at March on Washington and her experience with the danger of being jailed when participating in the Civil Rights movement.

Baez’ political involvement wasn’t limited to the Civil Rights movement. In 1964, she wrote a letter to the IRS saying that she wasn’t going to give sixty percent of her income tax to armaments. When pressed, she said that she would rather be a good person than pay for napalm to “dump on children.[10]” She continues speaking in this vein about her difficulty maintaining her position as a social rights advocate with the following lines, and her experience on talk shows during the Vietnam war:

“The average scenario went like this: I’d be invited out after a Teflon display or a quilting bee or a talking dog contest, and the interviewer would ask me something about my position on the war (You’ve been a real activist. You must feel pretty strongly about this . . .), and before I could get a sentence out he’d say, “Oh, just hold it a minute, we’ve got Bonzo Gritt here fresh from filming on the set of ’Forever America’ and he’d like to give his opinion,” and Bonzo Gritt would sit down and say “Well, Miss Buyezz, I’ve always admired your singing very much, but personally, I’m not gonna sit back and let the red plague creep across Indochina and around the world to our shores and swallow me up,” and the interviewer would say, “Thank you, Bonzo, and we’ll be back in a minute, after this message, …” and there I’d sit. And then, after we came back on, I’d light into them like a cheetah, telling Bonzo that if he were committed he wouldn’t be sitting in that chair, he’d be “over there” fighting on the front lines. Then I’d appeal directly to the roomful of middle-American mothers who had been on a six-month waiting list to see this show, asking them if they thought their boys wanted to go to Vietnam, and if those busses that and were there only because they’d gotten a letter in the mail telling them they had no choice. And the moms wouldn’t know whether to clap or boo, and then I’d sing, and no one would know what to think.

Finally, Joan Baez spent years studying non-violence at a school that she paid to create with the help of Roy Kepler and Holly Chenery. When forced to evacuate before they’d been up before the board of county supervisors, the “students” of the school held meetings everywhere from a local park to Baez’ house (which, for some reason, was technically illegal to use) [18]. Here she is in 1976 discussing her involvement with the school:

Ultimately, I hope that my presentation gives you insight into who Bob Dylan and Joan Baez were as people and how they contributed to the Civil Rights movement (and Baez to 20th-century social change more broadly). While Bob Dylan’s eccentricity makes him an interesting subject of study, and his lyrics are certainly compelling, Baez’ contribution to the movement shouldn’t be overlooked. She details in her autobiography how, at the inception of Dylan’s career, she “dragged my little vagabond out onto the stage,[10]” and how audiences that weren’t familiar with him tried to boo him off. Still, as Baez remarks, “Bob Dylan’s name would be so associated with the radical movements of the sixties that he, more than all the others who followed with guitars on their backs and rainbow words scribbled in their notepads, would go down forever in the history books as a leader of dissent and social change.” Her next sentence is telling of how ironic this is; she says: “I gather he doesn’t much care one way or the other [10].” In contrast, Baez certainly cared about her political and social legacy: her role within the Civil Rights movement, her founding of a school for non-violence, her public interviews, and her autobiography are all indicative of this Perhaps more perpetual and meaningful than Dylan’s, her legacy should be remembered as such.

Sources:

[1] •Editors, History com. “Civil Rights Movement.” HISTORY, https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/civil-rights-movement. Accessed 6 Dec. 2019.

[2] “Joan Baez Discography.” Wikipedia, 18 Aug. 2019. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Joan_Baez_discography&oldid=911436033

[3] “Bob Dylan.” Wikipedia, 12 Dec. 2019. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Bob_Dylan&oldid=930374973

[4] Ryan, Patrick. “Netflix Documentary ‘Rolling Thunder Revue’ Gives Intimate Look at Bob Dylan and Joan Baez’s Relationship.” USA TODAY, https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/music/2019/06/10/bob-dylan-joan-baez-relationship-heart-scorseses-netflix-documentary/1410315001/. Accessed 6 Dec. 2019

[5] Ray, Sanjana. “How Bob Dylan Changed the Course of History through His Music.” YourStory.Com, 24 May 2017, https://yourstory.com/2017/05/music-of-bob-dylan.

[6]“Bob Dylan: The Secret Life and Loves of a Musical Icon.” Independent.Ie, https://www.independent.ie/life/bob-dylan-the-secret-life-and-loves-of-a-musical-icon-35664688.html. Accessed 6 Dec. 2019.

[7] “The Inspiring Force Of ‘We Shall Overcome.’” NPR.Org, https://www.npr.org/2013/08/28/216482943/the-inspiring-force-of-we-shall-overcome. Accessed 8 Dec. 2019

[8] University, © Stanford, et al. “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.” The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute, 6 July 2017, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/march-washington-jobs-and-freedom.

[9] Editors, History com. “March on Washington.” HISTORY, https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/march-on-washington. Accessed 12 Dec. 2019

[10] Baez, Joan. And a Voice to Sing with: A Memoir. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2009

[11] “Medgar Evers.” Biography, https://www.biography.com/activist/medgar-evers. Accessed 12 Dec. 2019

[12] “Bob Dylan’s Tribute To Medgar Evers Took On The Big Picture.” NPR.Org, https://www.npr.org/2013/06/12/190743651/bob-dylans-tribute-to-medgar-evers-took-on-the-big-picture. Accessed 10 Dec. 2019

[13] Songfacts. When The Ship Comes In by Bob Dylan – Songfacts. https://www.songfacts.com/facts/bob-dylan/when-the-ship-comes-in. Accessed 10 Dec. 2019

[14] Swenson, Kristin, et al. “The Prophetic Joan Baez.” HuffPost, 12 June 2013, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-prophetic-joan-baez_b_3428665.

[15] Hughes, Charles. “Allowed to Be Free: Bob Dylan and the Civil Rights Movement.” Highway 61 Revisited: Bob Dylan’s Road from Minnesota to the World, edited by Colleen J. Sheehy and Thomas Swiss, NED – New edition ed., University of Minnesota Press, 2009, pp. 44–60. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv2n1.8.

[16] Dylan, Ben Corbett Ben Corbett has 20 years of experience as a music journalist focusing on American counterculture He has written extensively about Bob. “A Closer Look at Bob Dylan’s ‘Protest’ Songs.” LiveAbout, https://www.liveabout.com/bob-dylan-and-civil-rights-movement-1322012. Accessed 6 Dec. 2019.

[17] “Joan Baez | Biography, Music, & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Joan-Baez. Accessed 13 Dec. 2019

[18] Wallace, Kevin. Non-Violent Soldier. Sept. 1967. www.newyorker.com, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1967/10/07/non-violent-soldier