Flannery O’Connor was a novelist and writer of short stories who frequently drew from her own life and experiences to produce her creative work. Born in Georgia in 1925 as the daughter of two Catholic parents, both O’Connor’s Southern background and her spirituality frequently worked their way into her writing, often in tandem with her grotesque writing habits.1 O’Connor’s short story Good County People is a paragon of her Southern and spiritual obsessions in her writing. The title of the story itself points to its Southern origins; set in Georgia, Good Country People deals with the stereotype of the goodheartedness of country people, a stereotype O’Connor likely grew up all too familiar with. This stereotype is materialized in the form of Mrs. Hopewell, who represents the shortcomings of broadly attributing a quality to a certain group of people, believing that “good country people” embody the values of Christianity. Further, the story not only draws from O’Connor’s Southern background but also her religious background, dealing closely with the pitfalls of Catholicism and a central focus on Joy, a character with a committed devotion to nihilism.2

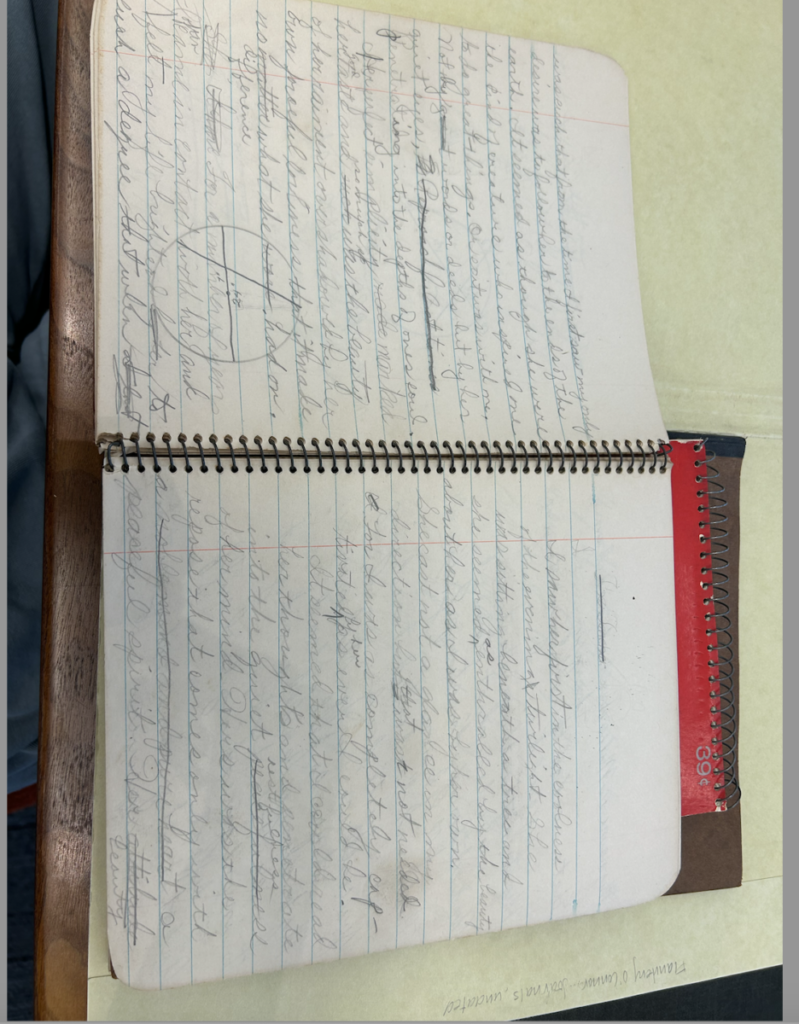

Good Country People is just one of many examples of how O’Connor often turned to her own life to inspire her creative work. O’Connor’s writing could not exist outside of the very specific context of her life experience, which is why it’s especially interesting to analyze her journals, as these scrawls of feelings and ideas could be the very things that inspired some of her most famous works. One notable journal is a spiralbound collection of writing, drawings, French, and even arithmetic. Oftentimes, there is no separation between these different types of journal entries; O’Connor will begin writing a story right on top of what seemed once to be a geometry assignment, or she’ll write around a drawing in the middle of the page. While this likely was just a tactic to conserve space, it can’t help but appear representative of the ways in which O’Connor was unable to extricate her writing from the other aspects of her life.

One particular drawing of note features a person sitting at a desk, typing on a typewriter. Lines drawn around the person’s body, hands, and the typewriter itself seem to point to the frantic quality of writing. The simple pencil sketch emits the feeling of being unable to get one’s thoughts out quickly enough. The close ties between O’Connor’s writing and her life suggest that she was constantly collecting inspiration for her writing with everything she did and experienced, which might lead to a frantic need to get everything written down. Additionally, the picture points to how frantic O’Connor may have been to put this specific feeling to paper; instead of writing about it, she wanted to quickly convey this frenzied feeling and did so in a drawing.

The journal also acts as a testimony to O’Connor’s writing process. One can identify O’Connor crossing out certain choices in pursuit of the perfect word (“Down the quiet hallways valleys desert sands”). Many initial grammar and spelling mistakes can also be observed (“wierd” instead of “weird”; “stareing” instead of “staring”; “gastly” instead of “ghastly”) which indicate that O’Connor’s revision process likely dealt as closely with grammar as it did with content. This is especially interesting to note alongside O’Connor’s report cards in grade school, which show her lowest grades to be under the spelling and grammar sections; while O’Connor’s grades rarely dropped below the 80s, marks as low as 70% can be observed in her spelling and grammar grades. It’s jarring to realize such an esteemed writer struggles with the more technical aspects of the English language, but this fact is also evidence that these technical skills are not at all what truly makes a talented writer.

One may also point out that this journal proves that O’Connor was inspired not only by her own life but from the lives of others. One page begins, “My name is John Alden, and I’m in a pickle.” While it does not seem that much came from this idea, it’s clear that the Mayflower crew member struck some sort of inspiration in O’Connor, who, like a sponge, seems to soak up inspiration from just about anything. Even notes within the journal that don’t specifically deal with creative writing further this point. For example, at one point O’Connor makes extensive notes about the functions of political cartoons. While these notes are very technical in nature – one may assume they are notes for a class – the point must be returned to that everything in a journal is, by nature, inextricably bound. The placement of these notes between drafts of O’Connor’s stories attributes a creativity to them that O’Connor may not have intended, but cannot be ignored. Perhaps as O’Connor sifted through her journals in search of inspiration, she not only turned to her creative drafts, but also to her academic notes.

While the above paragraph identifies evidence of O’Connor’s branching out and writing about topics more unfamiliar to her, this journal still also provides some solid, clear-cut examples of how she worked with the obsessions seen so frequently in her writing. As stated earlier, O’Connor’s work is often marked by Southern, Catholic tendencies. One example of how this manifests in her journal is a page marked at the top with the words “Writing as a Christian” succeeded by the following bullet points: “felix culpa”, “the radical opportunity”, and “truth resisting classification”. O’Connor appeared very intentional about the themes and ideas she wished to introduce in her writing through the lens of Christianity. Another moment that stands out is when O’Connor writes, “The reality of death has come suddenly upon us and the power of God has broken our complacency like a bullet in the side”. This line attests to O’Connor’s tendency to approach big, abstract topics such as death in the context of religion.

Overall, to read Flannery O’Connor’s journal is to gain a deeper understanding of her writing process. While most are only ever able to encounter O’Connor’s polished, final drafts, this journal demonstrates that there was an extensive process O’Connor had to go through in order to get her writing to this place.