James Dickey, born in 1923 in Atlanta, Georgia, was a well-known 20th-century poet known for his extensive body of work, including poetry collections, such as The Whole Motion: Collected Poems, 1945-1992 (1990) and The Eagle’s Mile (1990)1. Dickey, who coined his own style as “country surrealism,” crafted a unique literary style that combined the realms of unconscious and conscious thought, successfully conveying the decisiveness of reality and imagination2.

Dickey’s entrance into literature was preceded by his service in World War II as a member of the 418th Night Fighter Squadron, where he undertook over 100 combat missions3. His wartime experiences left an unforgettable mark on his writing, contributing to the raw and, at times, intense nature of his works, which have occasionally been labeled as controversial or violent. In an article titled “The Burden of James Dickey”, The Atlantic went as far as to characterize Dickey’s works as “Extremist” and referred to Dickey himself as “flawed” as the article explored the complex dynamics of Dickey’s life as described by his own son4.

In addition to his significant contributions to the world of poetry, James Dickey ventured into the realm of fiction, writing notable and influential novels, including the celebrated work Deliverance. The focus of this catalog, however, is on a lesser-known work from Dickey’s literary repertoire, the novel Alnilam. This artifact gives us a special look into how Dickey’s creativity developed and helps us better understand the many aspects of the author who wrote these words.

Alnilam (1987) was Dickey’s second novel, following 17 years after the publication of Deliverance in 1970. The title of the novel was derived from the belt of the Orion constellation. The direct translation from Arabic means “a belt of pearls.” Despite this delicate title, the novel is much more intense and takes from Dickey’s experience in the Night Fighter Squadron. The novel follows Cahill, a father, whose world is abruptly disrupted when he receives a telegram bearing the devastating news of his son’s tragic death in a training accident in the fictional town of Peckover, North Carolina. What makes this news particularly bewildering is that Cahill’s wife had left him 19 years ago, and he had no knowledge of having a son. Adding to the difficulty of his situation, Cahill has also lost his eyesight due to diabetes. The rest of the novel unfolds as it traces Cahill’s journey to bury his son’s remains. Throughout his travels, he is accompanied by Zack, a protective black wolf5.

Alnilam draws upon Dickey’s experiences during World War II to create a compelling narrative that challenges readers to untangle the themes surrounding warfare, blindness, and more. In particular, Dickey’s contrasting messages about flying, with one perspective casting a positive light and another referring to a plane as a “mutilation machine,” hint at a potential contradiction in Dickey’s recollections that made its way into the novel.

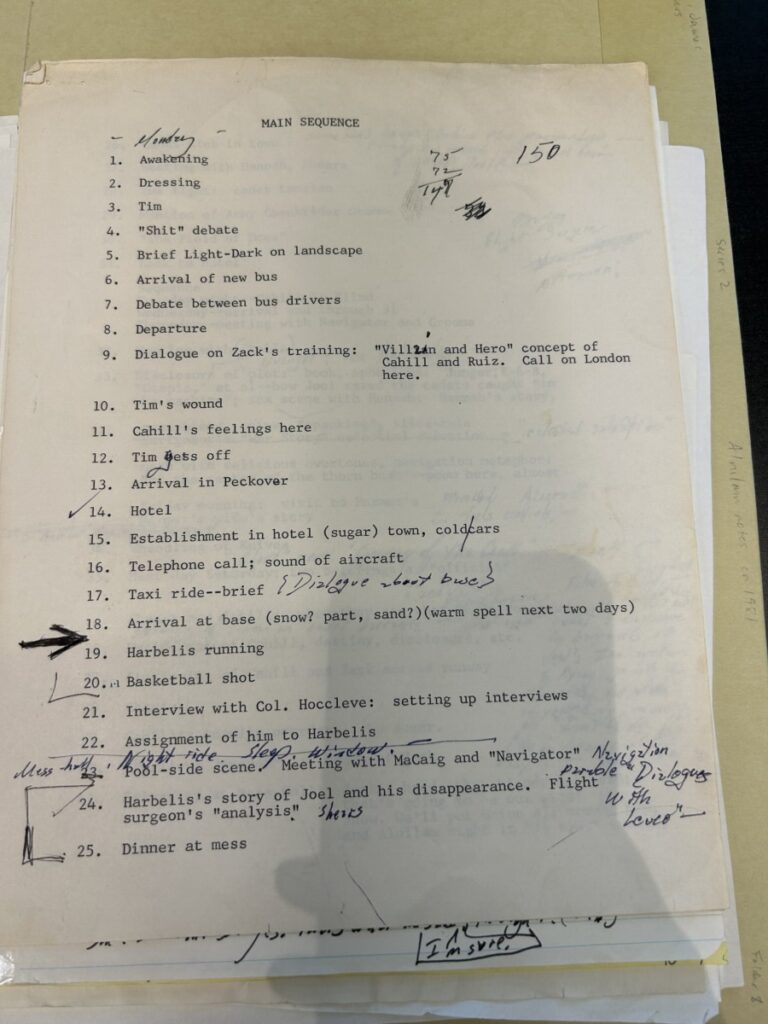

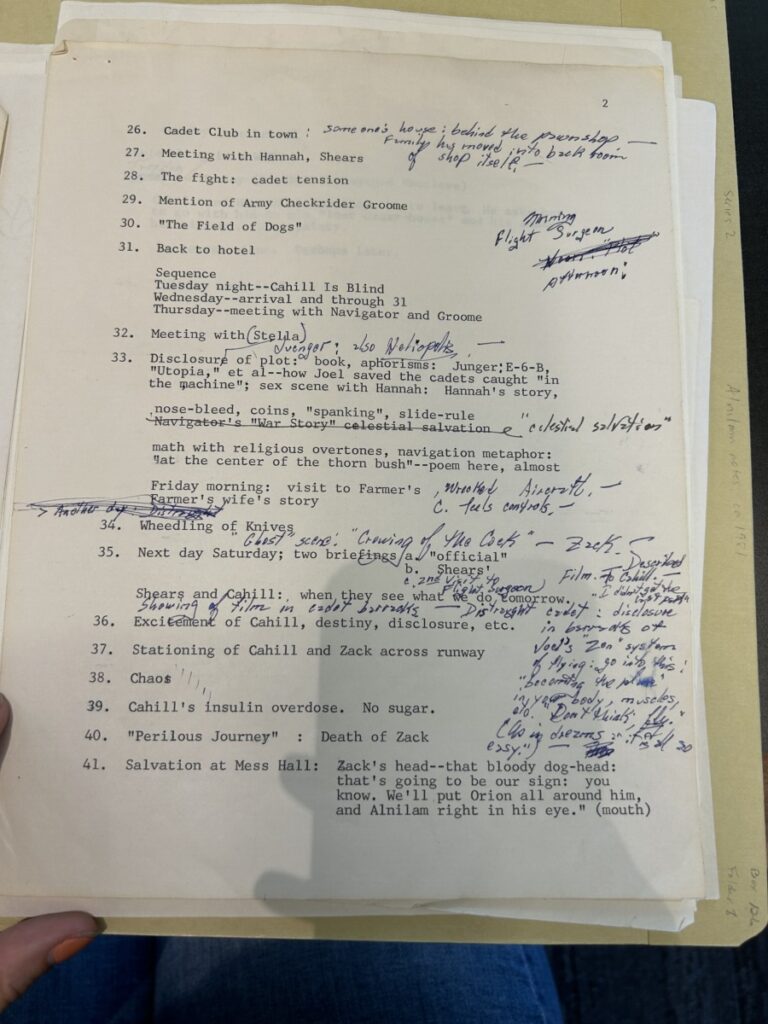

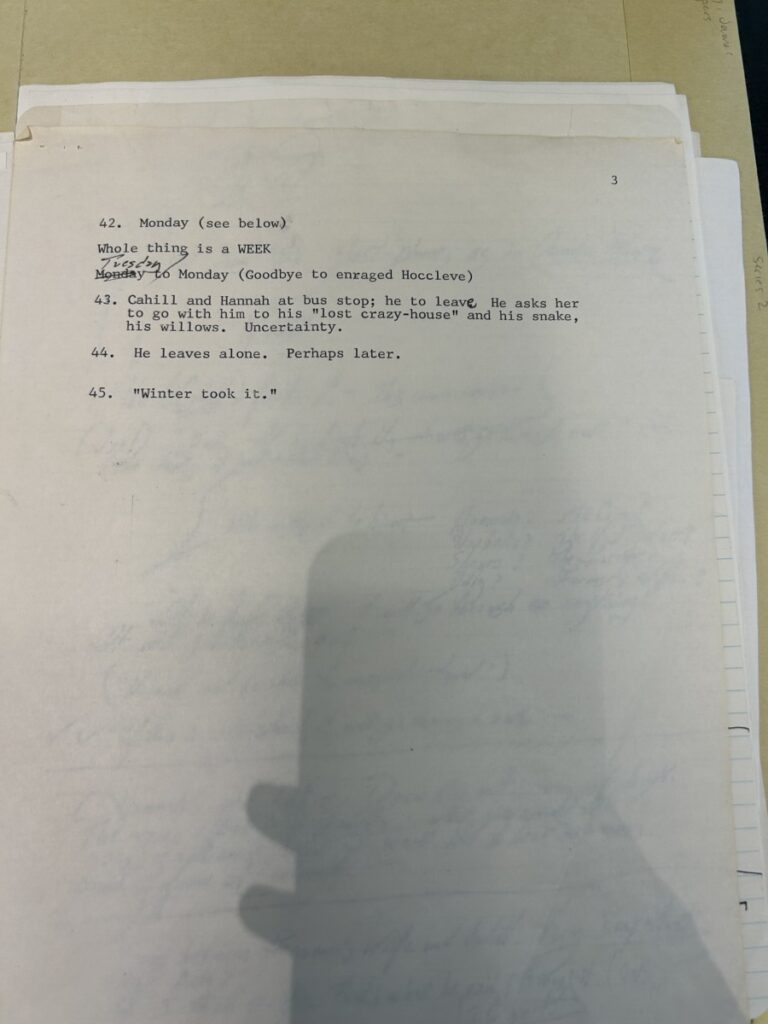

As evident in the three artifact images, James Dickey carefully crafted a “Main Sequence,” as he titled the first page6. In this sequence, Dickey outlined the 45 key events of the novel, assigning titles to each, like “Hotel” or “The Flight: Cadet Tension.” In a narrative filled with intricate subplots and conflicting dialogues, this outline serves as a testament to the invaluable aid it provided during the novel’s composition.

The title and numbered sequential events are typed on typewriter paper with handwritten notes throughout. Notably, several of the event headings are accompanied by additional typed notes. For instance, event #9, titled “Dialogue on Zack’s Training,” features this additional note off to the side in the margins: “‘Villian and Hero’ concept of Cahill and Ruiz. Call on London here.” This type of annotation appears periodically throughout the sequence of events.

Of greater interest, however, are the handwritten notes in pen that line the pages. At the top of the first page, Dickey scribed the word “Monday”, a subtle yet necessary detail. The typed details of event #42 further explains the significance of this note, revealing that the entire book unfolds within the span of just one week. The second page of the sequence is filled with pen markings, adding details not covered in the typed text. Dickey’s penmanship appears rushed, often messy, and occasionally smudged, hinting at an urgency as he recorded his ideas and revisions on this typed outline. These handwritten notes not only contribute to the clarity of the storyline but also provide additional information for certain events that were not initially typed.

Another interesting facet of these annotations is the use of two different ink colors. While the majority of handwritten edits are in blue, scattered throughout all three pages, there are additional notes written in black ink. The differing ink colors suggest the possibility that Dickey revisited this sequence multiple times for further note-taking or, less likely, engaged someone else in this early editing process. The consistently, however, in handwriting between the two ink colors leans towards the former.

James Dickey employed the method of outlining and editing on a “Main Sequence” document while working on his novels following the success of Deliverance. This approach is seen again in the notes for his novel, To the White Sea (1993), outlining the pivotal events to prepare for a more thorough outlining and editing process7. Dickey’s consistent use of this method, as exemplified in both Alnilam and To the White Sea, showcase the deliberate and thoughtful approach he brought to his creative process.

While less renowned than Dickey’s acclaimed novel Deliverance, critics were eager to engage with Alnilam upon its late-1980s release. Similarities between these first two novels of Dickey’s are few with a stark difference in writing style and accessibility to readers. Alnilam was published as a dense 682 page novel with an occasional use of experiential writing forms, understood only by a very dedicated reader8. While both novels share the common theme of a man struggling to survive, the approaches are markedly distinct. Alnilam delves into the theme with a greater degree of nuance, weaving dual realities and narratives into the pages.

Alnilam remains one of just three works of long fiction James Dickey published in his lifetime. In this exploration into James Dickey’s thought process of outlining Alnilam, we gain insight into the meticulous approach he applied to his writing. It serves as both a testament to Dickey’s evolution as a writer as well as the distinct narrative style he expressed in this novel that has challenged readers and literary experts alike.

References

Batchelor, John Calvin. “JAMES DICKEY’S ODYSSEY OF DEATH AND DECEPTION.” Washington Post, May 24, 1987. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/entertainment/books/1987/05/24/james-dickeys-odyssey-of-death-and-deception/655732a5-1c72-4e1f-8f52-a16e2c6fe241/.

Davison, Peter. “The Burden of James Dickey.” The Atlantic, August 1, 1998. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1998/08/the-burden-of-james-dickey/377173/.

Dickey, James. “Alnilam Notes, ca 1981.,” n.d. MSS 745. James Dickey Papers. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University Libraries, Atlanta, GA. Accessed October 20, 2023.

“To the White Sea, Holograph Notes [Some on Napkins], Outlines & Related Correspondence.,” n.d. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University Libraries, Atlanta, GA. Accessed October 20, 2023.

Foundation, Poetry. “James L. Dickey.” Text/html. Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, October 27, 2023. Https://www.poetryfoundation.org/. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/james-l-dickey.Mambrol, Nasrullah. “Analysis of James Dickey’s Novels.” Literary Theory and Criticism, May 30, 2018. https://literariness.org/2018/05/30/analysis-of-james-dickeys-novels/.

- Foundation, “James L. Dickey.” ↩︎

- Foundation. ↩︎

- Foundation. ↩︎

- Davison, “The Burden of James Dickey.” ↩︎

- Batchelor, “JAMES DICKEY’S ODYSSEY OF DEATH AND DECEPTION.” ↩︎

- Dickey, “Alnilam Notes, ca 1981.” ↩︎

- Dickey, “To the White Sea, Holograph Notes [Some on Napkins], Outlines & Related Correspondence.” ↩︎

- Mambrol, “Analysis of James Dickey’s Novels.” ↩︎

I have an uncorrected proof of Dickey’s ‘Zodiac’ which is full of the same type of notes and corrections he penned throughout and the last two pages are full of his notes