Throughout Jewish history, the topic of intermarriage has been hotly debated: can intermarriage be condoned, or is it a step towards assimilation and loss of Jewish culture? Mel Leventhal was born in 1943 and grew up in Brooklyn in a large Jewish community. Both of his parents were Jewish, and he grew up practicing Judaism. He received both his undergraduate degree and JD from New York University in the 1960s. After graduating from law school, Leventhal moved from Brooklyn to Jackson, Mississippi, where he began to devote his life to the Civil Rights Movement.

In Mississippi, Mel Leventhal worked as an NAACP attorney fighting specifically for the desegregation of Southern schools. While in Mississippi, he worked on voter registration drives where he met writer Alice Walker. The couple got married in 1967, but after a tumultuous nine years, the two got divorced in 1976, having suffered “under the strains of an interracial relationship in an inhospitable land.” The “inhospitable land” refers to being a married interracial couple in a state where interracial marriage was illegal. The couple got married in New York because, in 1967, interracial marriage was illegal in Mississippi, the state they were living. They were one of the first legally married interracial couples in Mississippi. For some context, in Mississippi at the time, marriage was prohibited between white people and black people or descendants of black people through the fourth generation. Additionally, the penalty for intermarriage in the state was either a $500 fine or ten years imprisonment each, and the marriage was automatically considered void.

Like many Jewish parents, Mel Leventhal’s mother, Miriam Leventhal, was vehemently opposed to her son marrying someone who was not Jewish. According to Leventhal and Walker’s daughter’s memoir, her grandmother rejected Mel’s marriage to a black woman and often told her granddaughter, “Don’t ever forget… you’re a Jew! I don’t care what Mama and Daddy say.” Miriam Leventhal’s view on intermarriage is quite popular in the Jewish community. Rabbi David Einhorn, one of the most influential leaders of Reform Judaism in the United States from the mid-1800s, referred to intermarriage as “a nail in the coffin of the small Jewish race.” Around the time of Walker and Leventhal’s marriage, a shift was seen in how Jewish leaders began classifying Judaism. Many Jews began to see Jewishness as a racial identity rather than a religious identity to allow children from intermarriage to claim Jewish identity despite Jewish law. According to Jewish law, for a child to be considered Jewish, the mother must be Jewish; however, this shift in how Jewishness was viewed allowed more people to identify as Jewish and with the Jewish community. Despite her strong disapproval of her son’s intermarriage, based on Rebecca Leventhal’s account, Mel Leventhal’s mother still seemed to view Rebecca as Jewish and accept her, which would not have been the case a hundred years prior.

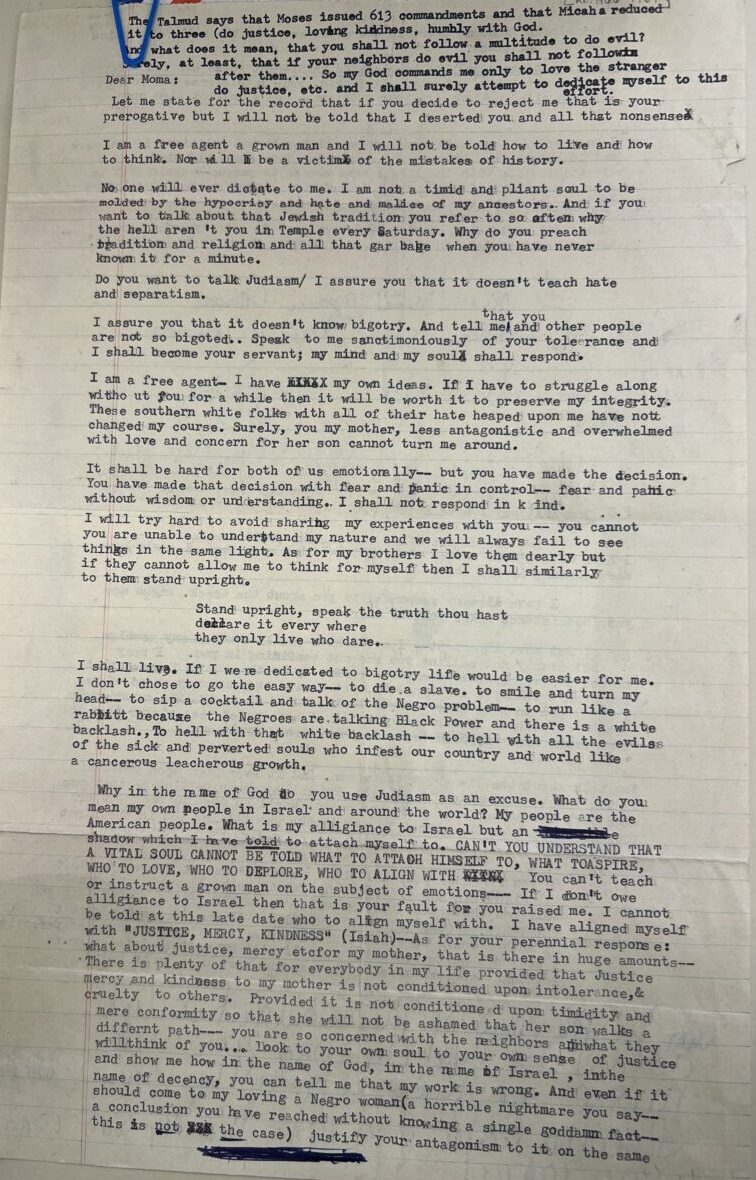

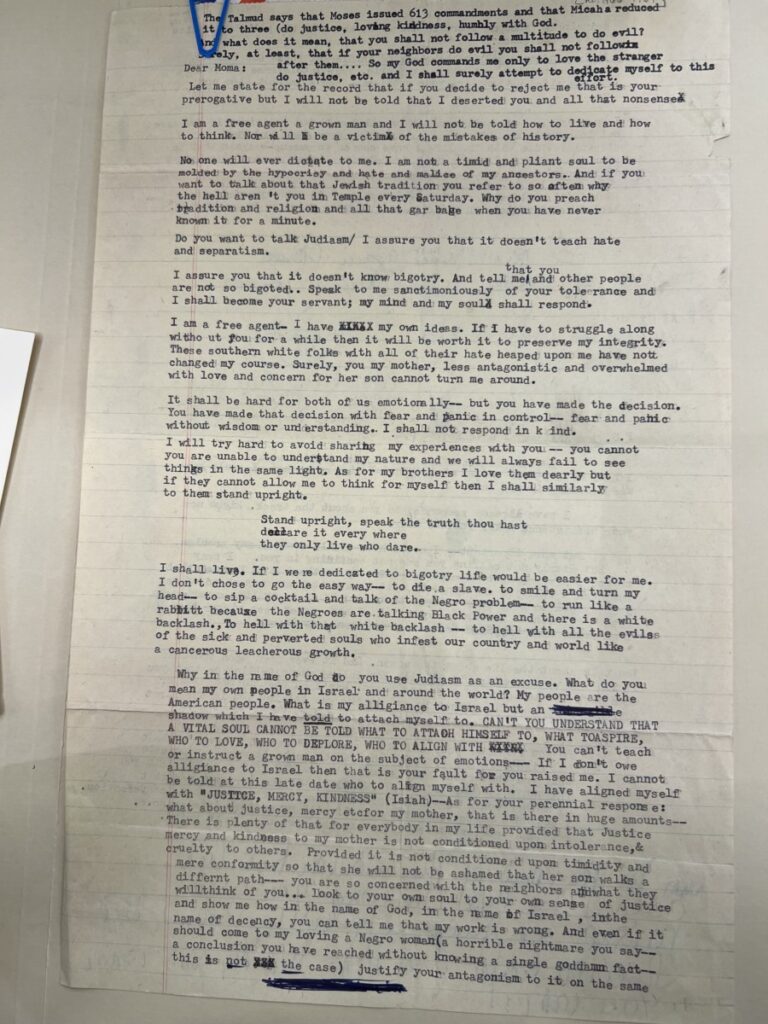

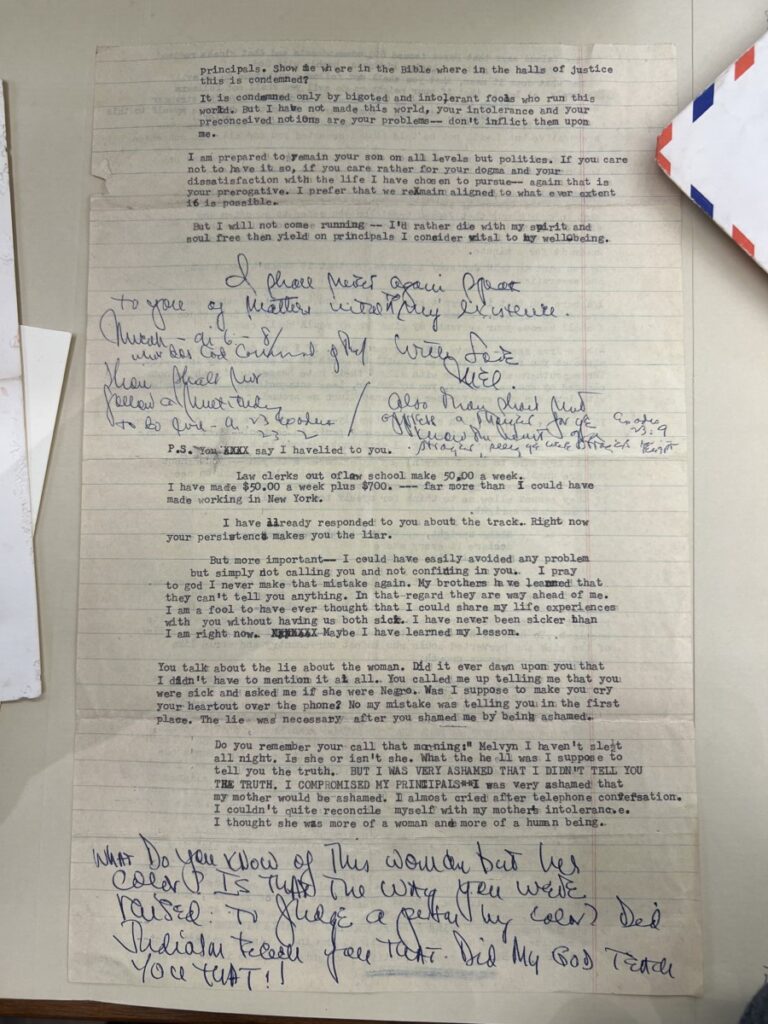

Now, with the proper background on Mel Leventhal and Alice Walker’s relationship and the Jewish perspective on intermarriage, it will be simpler to understand the letter that Leventhal wrote to his mother during his relationship with Walker found in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University in the Alice Walker papers. While the letter is undated, it is safe to assume that it was written at some point in the mid-60s during the beginning of his relationship with Alice Walker. Mel Leventhal wrote this letter to his mother, Miriam Leventhal, and delves into Jewish thought and the growing rift between Mel and his mother over his relationship with Alice Walker, a black non-Jewish woman. The two-page letter was written on a typewriter, has words crossed out with exes, and also has pen in the margins and between lines added later.

Firstly, there is a short bit of text at the top of the first page that seems to have been added later using darker typewriter ink that provides a strong thesis for the letter. In this text, he mentions the commandments from the bible and the prophet Micah’s condensing of them into three commandments: do justice, loving-kindness, and walk humbly before God. The mention of Micah’s three commandments acts as support for his argument that his mother’s disapproval of his relationship with a black woman goes against Jewish belief and is built on bigotry and hypocrisy. In only the third paragraph, Leventhal angrily writes, “If you want to talk about that Jewish tradition you refer to so often, why the hell aren’t you in Temple every Saturday. Why do you preach tradition and religion and all that garbage when you have never known it for a minute.” He raises the point that his mother uses religion as an excuse for not approving of his life choices but barely engages with religion in her own life. Throughout the remainder of the letter, he delves into why Judaism should support his decision, quotes bible verses, and explains the divide he feels forming between him and his mother.

In Mel Leventhal’s letter to his mother, he does not mention that his mother may disapprove of his relationship because of Alice Walker’s religion, only her race. Leventhal explains that Judaism does not teach hate or separatism but rather fosters love and community. In the letter, he quotes the bible a few times in pen. The bible verses he cites are “do not follow the crowd in doing wrong” Exodus 23:2 and “do not oppress a foreigner” Exodus 23:9. These quotes help Leventhal make his point that Judaism does not condone bigotry. The final point that hits the nail on the head is encompassed in this quote where Leventhal says for the first time that he loves a black woman and exposes his mother’s intolerance:

“Look to your own soul to your own sense of justice and show me how in the name of God, in the name of Israel, in the name of decency, you can tell me my work is wrong. And even if it should come to my loving a Negro woman (a horrible nightmare you say – a conclusion you have reached without knowing a single goddamn fact – this is not the case) justify your antagonism to it on the same principals. Show me where in the Bible where in the halls of justice this is condemned?”

Finally, Leventhal explains the shame he felt telling his mother about being with someone that she would disapprove of and indicates that his relationship with her would be different from now on unless she decides to support him.

Ultimately, Miriam Leventhal got what she wanted in the end. Leventhal and Walker got divorced in 1976, and Mel Leventhal ended up getting remarried to a Jewish woman. After the divorce, they decided that their daughter Rebecca would switch off between them and their extremely different worlds every two years. Mel Leventhal moved up to New York and started a more suburban life, while Alice Walker moved to a more cosmopolitan world in San Francisco. Leventhal’s relationships matched a 1970s study about the divorce rate of Jewish intermarried couples. In the study, it was found that the divorce rate was 4.7% when both partners were Jewish, but when only the husband was Jewish, the rate rose to 25%. From this data, it is evident that while this letter is technically about Mel Leventhal and his relationship with his mother after deciding to be in a relationship with someone who is not Jewish, it is also a letter about the generational divide within Jewish communities about intermarriage and how this divide affects families.

Bibliography

Barnett, Larry D. “Anti-Miscegenation Laws.” The Family Life Coordinator 13, no. 4 (1964): 95–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/581536.

Ellman, Israel. “Jewish Intermarriage in the United States of America.” In The Jewish Family: A Survey and Annotated Bibliography, 25–62. University of Toronto Press, 1971. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctvfrxm66.7.

Goldstein, Eric L. “‘Different Blood Flows in Our Veins’: Race and Jewish Self-Definition in Late Nineteenth Century America.” American Jewish History 85, no. 1 (1997): 29–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23885595.

Lester, Julius. “Review: Black, White and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self Rebecca Walker.” Shofar 22, no. 1 (2003): 136–37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42944619.

Mehta, Samira K. “You Are Jewish If You Want to Be: The Limits of Identity in a World of Multiple Practices.” In Beyond Jewish Identity: Rethinking Concepts and Imagining Alternatives, 17–35. Academic Studies Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1zjg2x1.5.

Mel Leventhal Letter to Miriam Leventhal, Undated, Collection No. 1061, Box 33, Folder 2, Alice Walker Papers Collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University.

Review of Alice Walker’s Love Stories, by Alice Walker. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 31 (2001): 132–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/2679210.

Whitfield, Stephen J. “The Braided Identity of Southern Jewry.” American Jewish History 77, no. 3 (1988): 363–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23883313.