Robert Penn Warren was born in Guthrie, Kentucky, in 1905. He attended Vanderbilt University, the University of California, and Yale University before crossing the Atlantic to attend Oxford University in 1928. In 1927, Penn Warren met his first wife, Emma Brescia, and the two secretly married in the summer of 1929. In 1951, Penn Warren and Brescia divorced, and he went on to marry Eleanor Clark in 1952. They had two children, Rosanna Phelps Warren and Gabriel Penn Warren.

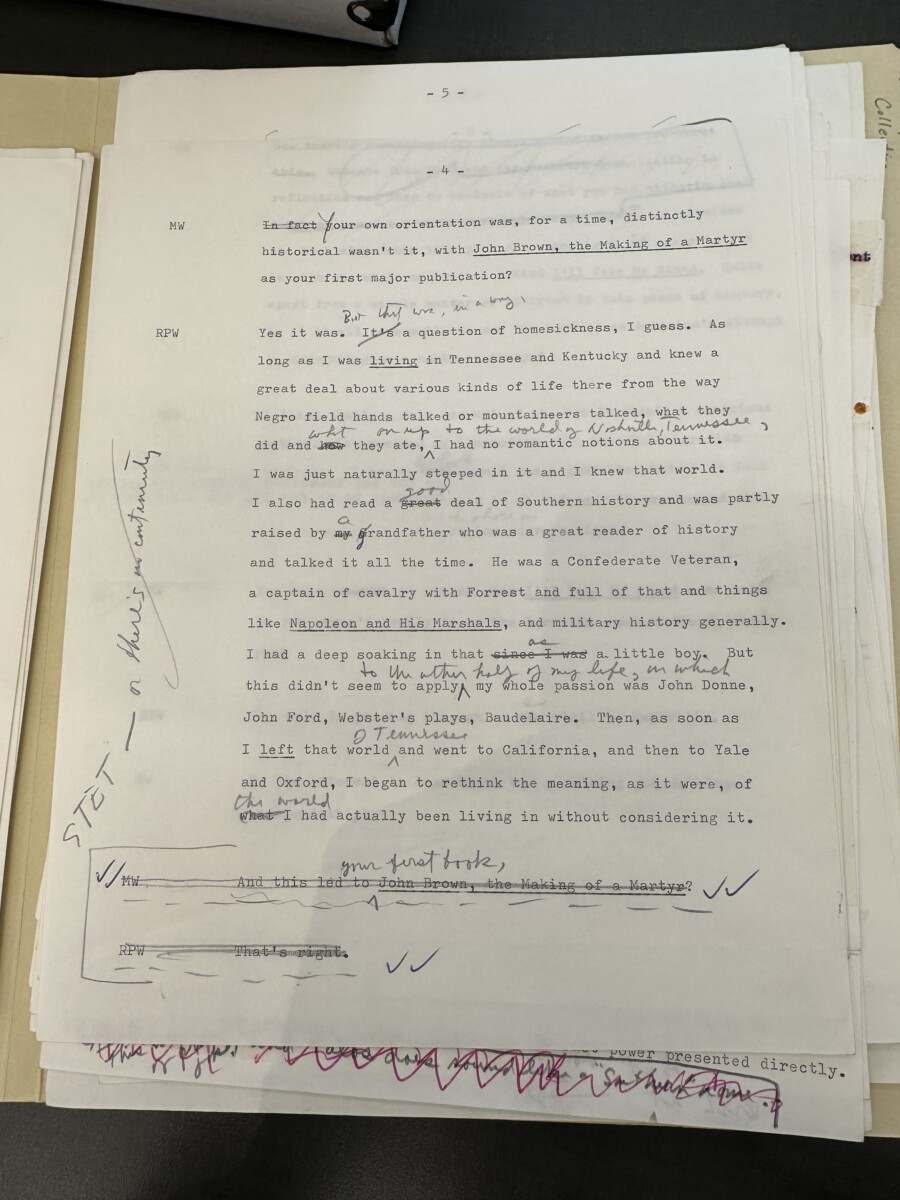

The specific artifact I want to discuss is labeled “Interview w/ Robert Penn Warren, typescript w/ corrections.” This artifact details Marshall Walker interviewing Robert Penn Warren, asking questions about Warren’s influences growing up and the influences on his most famous works. The interview consists of over 35 pages, all typed out using a typewriter, with corrections handwritten by either Walker or Warren on every page. Understanding who influenced Warren in his life is culturally important for Southern Literature, as he is one of the most influential Southern writers in the history of the United States, having won Pulitzer Prizes for both fiction and poetry. Within the artifact, Warren goes in depth about his most famous works, specifically All The King’s Men. This article details the findings in order of the interview and relevance to RP Warren.

Robert Penn Warren was among the last members of a major Southern literary movement, The New Criticism, shortly after World War I. He developed this style as a member of the Fugitives, a group of Vanderbilt teachers and students who discussed trends in American life and literature, and later as a member of the Agrarians, former Fugitive members who reunited in the late 1920s to extol the virtues of the rural South. Throughout his career, Warren’s main focus was on poetry and fiction, with a slight preference for poetry. In the interview, Marshall Walker states, “Warren began as an enlightened conservative Southerner. Like his close associates, John Crowe Ransom, Donald Davidson, Allen Tate, and Andrew Lytle, he was acutely aware of the gulf widening between an America moving further into material progress and a minority of artists and intellectuals who saw themselves as custodians of traditional values.”

Warren’s earliest published novel, “Night Rider” (1939), focused on the tobacco war (1905-1908) between small tobacco growers and large tobacco companies. His first set of poems, “Thirty-Six Poems,” was released in 1936. Warren revealed his poetry was deeply influenced by Thomas Hardy, stating, “Hardy’s influence was the notion of fate, as fatalism was deeply ingrained in the Southern mind. In the interview Warren brushes off any questions regarding his past as Warren’s early writings reveal a close relationship between his early political and literary ideologies, including his racist thoughts. Warren even attacked his former colleague, Thomas Mabry, who had taken a job at Fisk, the historically black university in Nashville, repeatedly using offensive language in his attack on both Mabry and the article writer, C. Hartley Grattan.

Robert Penn Warren’s most famous novel, “All the King’s Men,” can be seen as representing the great American tradition of Populism. Marshall Walker informs Warren the novel is “the most widely read and most highly regarded of your novels but also the story that has occupied you the longest.” Warren acknowledges that the time it took to complete the final play version, nearly 23 years, is embarrassing. He credits his dissatisfaction with the play as the reason for writing the novel. Warren reveals that his influences for the play include Machiavelli, Guicciardini, William James, and Dante. His long immersion in Dante is evident in the play, with characters like the usurer and the great banker straight out of Dante’s Circle.

In Warren’s novels, there is a clear emphasis on what Walker refers to as “the vitality of Southern history.” Much of Warren’s subject matter drew inspiration from narratives, ballads, and folk legends he encountered while growing up in Kentucky and Tennessee. Warren underwent a difficult phase of self-discovery when he began traveling the world, as he revealed to Walker, “Yes, it was. It’s a question of homesickness, I guess… I was partly raised by a grandfather who was a great reader of history and talked about it all the time. He was a Confederate Veteran, a captain of cavalry with Forrest… as soon as I left that world and went to California, and then to Yale and Oxford, I began to rethink the meaning, as it were, of this world I had actually been living in without considering it.”

Warren’s style of The New Criticism gained prominence in the 1930s and 1940s as a reaction to what many critics saw as the limitations of earlier forms of literary analysis, including historical and biographical criticism. Several key figures are associated with the New Criticism movement, including John Crowe Ransom, I.A. Richards, Cleanth Brooks, R.P. Blackmur, and Allen Tate. These scholars and critics played a significant role in shaping the movement and its principles. New Critics advocated for close reading of a text, examining it in great detail, paying careful attention to language, imagery, symbolism, and other elements within the text itself. They rejected the idea of the “intentional fallacy,” which argued that a text’s meaning could only be understood by considering the author’s intentions. Instead, they believed that a text should be analyzed independently of the author’s intentions.

This idea of the “intentional fallacy” is reminiscent of the 19th-century poet John Keats, who coined the term “negative capability.” Keats described the idea that great artists, like Shakespeare, have the ability to embrace and even revel in the uncertainties and mysteries of life and human experience. Rather than seeking clear-cut answers or absolute truths, they are comfortable with the unresolved and the contradictory. This capacity allows them to explore the full range of human emotions and experiences in their creative works, producing truly profound and emotionally resonant art.

Bibliography:

Interview w/ Robert Penn Warren, Typescript w/ Corrections, Box 1, Folder 14, MSS 682, Robert Penn Warren Collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library (MARBL), Emory University.

Millichap, Joseph R. “Robert Penn Warren’s West.” The Southern Literary Journal, vol. 26, no. 1, (1993): 54–63. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20078084.

Sillars, Malcolm O. “Warren’s All the King’s Men: A Study in Populism.” American Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1957): 345–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/2710534.

Spears, Monroe K. “Robert Penn Warren.” The Sewanee Review 94, no. 1 (1986): 99–111. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27544554

.

Szczesiul, Anthony. “The Conservative Aesthetic of Warren’s Early Poetry.” Style 36, no. 2 (2002): 222–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.36.2.222.

Warren, Robert Penn. “Pure and Impure Poetry.” The Kenyon Review 5, no. 2 (1943): 228–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4332404.