This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

January 1921: Prana-Film has a grand vision of the future of horror. Films they planned to create included Hollentraume (Dreams of Hell) and Der Sumpfteufel (The Devil of the Swamp).

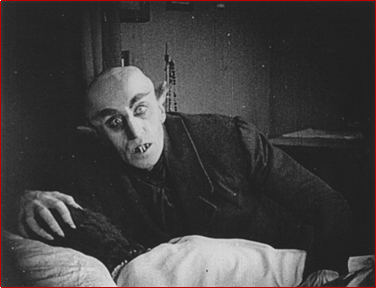

The only titled they created, however, was Nosferatu.

Perhaps Albin Grau, the film’s producer and a famed occultist, should not have drawn such inspiration from Dracula. Renaming Jonathan to Hutter, Mina to Ellen, and Dracula to Orlok does not a fair use claim make.

Perhaps Prana-Film, who never sought approval from the Stoker family, should not have stated it was “freely adapted” from Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Most importantly, perhaps Prana-Film should not have underestimated the fury of the still-living widow of Bram Stoker: Florence Stoker (Skal, 1990, p. 79).

April 27th, 1922: Florence Stoker officially joins the British Incorporated Society of Authors, intending for the society to sue on her behalf (Skal, 1990, p. 77).

February, 1925: Stoker, realizing she will not be receiving any money from this rapidly collapsing film company, argues for the destruction of all copies of Nosferatu—a film she has never seen (Skal, 1990, p. 77)..

July 20th, 1925: The owners of the assets of Prana-Films give in. Withdrawing their appeal, there is nothing to stop Nosferatu from being destroyed.

There is no confirmation it actually is destroyed (Skal, 1990, p. 96).

October, 1925: Florence Stoker is invited to join a newly formed organization, the Film Society, dedicated to preserving and showing important films. This group included the likes of playwright G.B. Shaw and H.G. Wells. On the docket for their first screening?

Retitled “Dracula by F.W. Murnau”, after the film’s 6’4, gay director, it was Nosferatu (Skal, 1990, p. 98).

Florence again attempted to pursue another legal battle, this time against Ivor Montagu, organizer of the film society. Montagu, a vegetarian communist who would go on to work with Alfred Hitchcock, claimed that the showing would be free, and private, on top of the fact that the film had no monetary value in London. And indeed it didn’t. An importer attempted to show the film at several theaters, and censors deemed Nosferatu “too horrible”. And so Nosferatu was shown, preserved, and made its way, like the vampire it was based on, around the world (Skal, 1990, p. 100).

It should be noted that Skal’s sourcing comes from letters in the British Library Archives and Manuscripts, so he tells the piece from her perspective. In his book, The Nosferatu Story, Rolf Giesen goes into great detail regarding Prana’s financial problems and mismanagement, so the blame for the studio going under cannot be placed on Stoker. Her lawsuit, however, is indeed what caused the film’s negatives to be order to be destroyed (Giesen, 2019, p 88).

Sources:

Giesen, Rolf. (2019). The Nosferatu Story: The Seminal Horror Film, Its Predecessors, and Its Enduring Legacy. McFarland and Company, Inc. Publishers.

Skal, D. (1990). The English Widow and the German Count. Hollywood Gothic : The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel to Stage to Screen. (pp. 77-102). New York: Norton.