Colombia’s Cultural Landscape in the 19th and Early 20th Century: Women’s Contributions

Colombia’s cultural landscape during the 19th and early 20th centuries was shaped by its turbulent political history, marked by frequent civil wars, shifting regimes, and the search for a cohesive national identity. Within this environment, cultural production became a crucial tool for intellectuals and artists to navigate and respond to national challenges. Women, despite societal constraints, increasingly became active participants in this cultural sphere, contributing through literature, journalism, and the arts.

Women’s Education and Literary Engagement

During the 19th century, women’s access to formal education in Colombia was limited, particularly outside urban areas. However, the establishment of schools for girls in cities like Bogotá, Medellín, and Cartagena provided elite and middle-class women with opportunities to engage in intellectual pursuits. This access was critical for fostering a generation of female writers and thinkers who began to assert their voices in national and regional cultural dialogues.

Soledad Acosta de Samper was one of the most prominent figures of this period. As a novelist, essayist, and historian, Acosta de Samper explored themes such as religion, patriotism, and women’s education, often addressing her works to a female audience. Her prolific contributions to literature and journalism, including her work with La Mujer magazine, positioned her as a central figure in Colombia’s cultural life, advocating for the intellectual and moral upliftment of women as essential to nation-building.

Participation in Journalism and Periodicals

The rise of print culture in 19th-century Colombia provided women with an avenue to participate in public discourse. Female intellectuals contributed to and edited magazines and newspapers, using these platforms to address social issues, promote educational reform, and comment on the political turmoil of the era. Publications like La Mujer and El Mosaico featured women’s writings that reflected their growing awareness of gender inequality while often reinforcing traditional moral values.

These periodicals also served as spaces for women to build intellectual networks, exchange ideas, and influence public opinion. Although these writings frequently aligned with the Catholic Church’s emphasis on virtue and morality, they also began to challenge women’s exclusion from public and intellectual life.

Contributions to Art, Music, and Theater

While women’s participation in literature and journalism is more widely documented, their contributions to other cultural fields were equally significant. In the realm of music, Colombian women played a vital role as composers, performers, and patrons of the arts, though their contributions were often confined to private or religious settings.

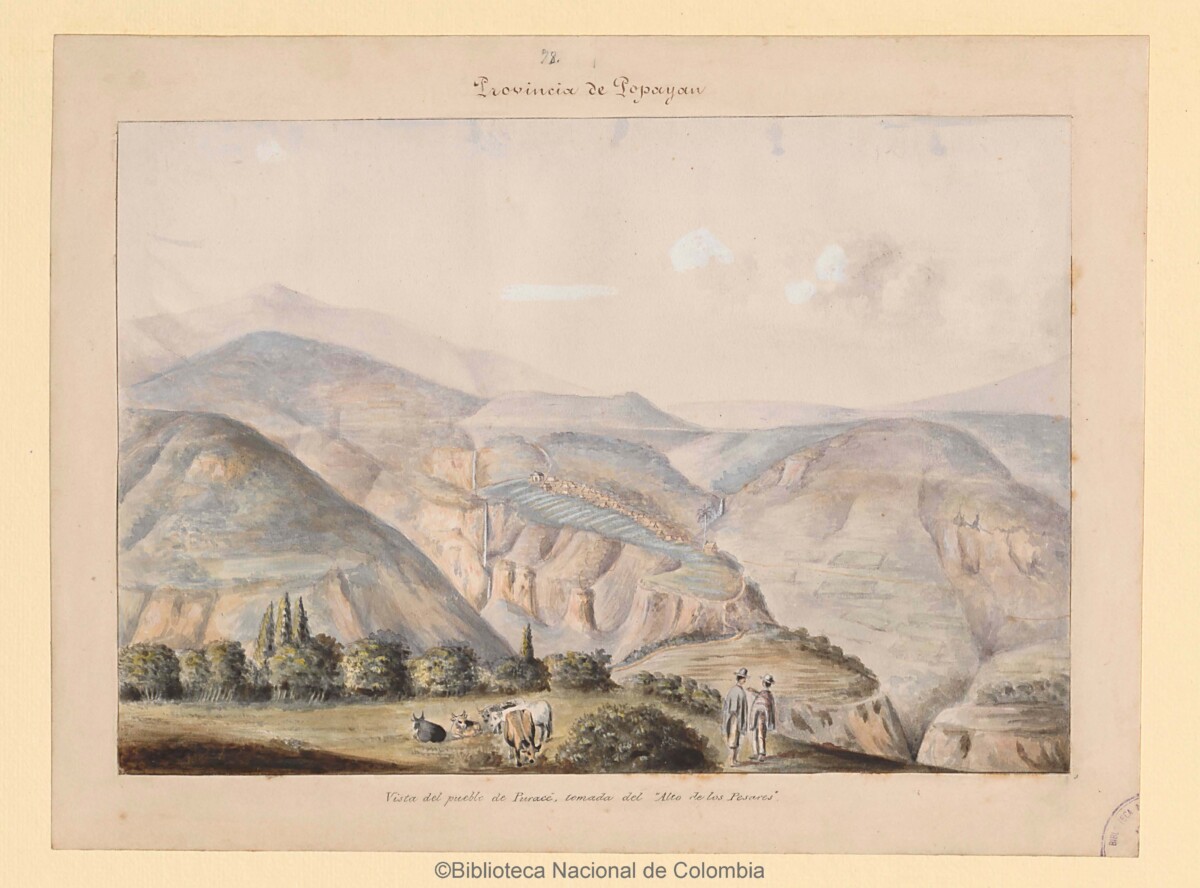

Women also began to participate in theater and visual arts during this period, albeit in limited capacities. These artistic expressions were often tied to nationalist themes, reflecting broader efforts to define Colombia’s identity amidst regional and political fragmentation.

Nation-Building and the Role of Women

As Colombia transitioned from a colonial society to an independent nation, women’s cultural contributions were frequently framed within the discourse of nation-building. Writers like Acosta de Samper emphasized the importance of women’s moral and intellectual roles in shaping a virtuous and cohesive society. This framing both reflected and perpetuated the era’s gender norms, positioning women as moral guides while restricting their participation in overtly political or public spheres.

At the same time, the intellectual and artistic work of Colombian women revealed subtle acts of resistance to these limitations. By engaging in cultural production, they expanded the boundaries of acceptable female behavior, laying the groundwork for later feminist movements.

Race, Class, and Exclusions

As in Brazil, Colombia’s cultural sphere was marked by exclusions based on race and class. Afro-Colombian and Indigenous women were largely marginalized from the elite cultural networks of the period. Their cultural expressions, rooted in oral traditions and community practices, were often overlooked or dismissed by dominant narratives. However, these contributions remain vital to understanding Colombia’s diverse cultural heritage.