One of the journal prompts that we received in class was about the different methods we had used to learn about the structure of the retina. I found this topic to be particularly interesting because it made me think about how the process of learning can be achieved through multiple mediums; and different mediums can often tend to work differently on different individuals. In trying to understand the structure of the eye, one could simply look at a scientific diagram that has been drawn to scale and get a fair idea of the number of different structures that make up the organ. Additionally, one could also do a combined analysis, as we did in this class, of both artistic and scientific representations of the same structure. In doing the latter, I found that I was able to gain both a quantitative as well as a qualitative impression of the matter. While science gave me a sense of perfection and austerity, art gave me a sense of imperfect brilliance: sensory stimulation in the retina is indeed dependent on wavelengths, reflections, and refractions; but the neurones are not all that well lined up like the assembly of troops for a march-past. They come in different shapes and sizes and they cannot possibly detect every single stimulus that comes their way. They are certainly very complex in their design and they form an intricate network to transfer signals at an incredible speed. Yet, we are limited in our abilities of sight, and we even have a blind spot. In fact, imperfections capture the very essence of evolution!

As someone who grew up in a Montessori classroom for almost eight years, I experienced most of my learning through engaging all five of my senses: sight, tactile, auditory, smell, and taste. By working with different kinds of materials, those that differed in shape, colour, texture, and size, I was able to form a mind-body connection every time I learnt something new. While looking at an artistic impression of the retina and then actually painting my own interpretation of what I saw by using different colours to represent different regions, I was taken back to my early days in the Montessori classroom. I was reminded of how this process activated a motor-skill oriented understanding of something and enabled one to form a long-term memory of it. The entire act allows for one to actually get a “feel” of what they are learning and this can be more beneficial than merely memorising a fact and expecting the brain to hold on to it forever.

An old picture of me working with Movable Alphabets- a Montessori Material.

It involves identifying pictures and then naming them. The vowels are blue and consonants are pink.

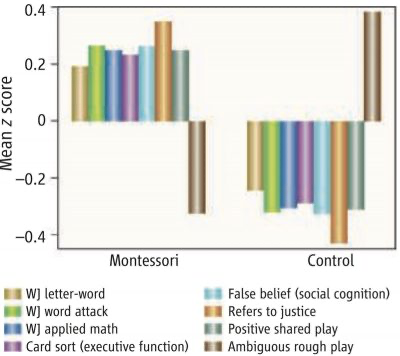

In a paper I came across recently on Montessori Education, a certain study revealed that Montessori children obtained higher scores on both academic and behavioural tests as compared to children from other non-Montessori systems of education. (Lillard et al. 2006). The authors of the paper also speak about how the Montessori method of using different learning materials that encourage the development of multiple sensorial abilities allowed Montessori students to outperform students from other backgrounds by demonstrating superior social cognition and executive control. Learning about these results made me think about the magnitude of the impact that such pedagogies can have on the intellectual development of a person. The concept of a hands-on approach to learning through the use of materials encourages the development of multiple areas of the brain at the same time, and this phenomenon can be especially beneficial in the early years of life. To give an example in context of the Montessori Method, the child, while tracing out different geometric shapes, is unwittingly practicing their fine-motor skills. This process will enable them to pick up the art of writing at a much faster pace than the average child. (Gobry, 2018). Montessori once said, The hand is the instrument of intelligence. The child needs to manipulate objects and to gain experience by touching and handling.” (The 1946 London Lectures). What Montessori observed back then, in an age where technology wasn’t as advanced as it is today, has gained a great amount of backing in modern research about the benefits of taking hand-written notes, for example, over notes on a computer. The tactile and kinaesthetic aspects of writing offer significantly greater memorisation and recollection abilities, ultimately giving rise to better performance in academically challenging situations. (Stephens, 2016).

As we look ahead into the future and see advanced technologies and artificial intelligence taking over many of the roles previously performed by human beings, I think that it’s interesting to recognise the fact that many of these roles (such as the mechanical acts in manufacturing industries) were fundamentally dependent on the effective use of our motor abilities. The acts of screwing a door onto a car or stitching together fabrics with a needle in order to produce a piece of clothing, for example, certainly require a decent level of dexterity and fine-motor skills. But as machines now perform roles such as these and many more with great speed and efficiency, and human beings are allowed to assume more passive roles that involve monitoring this technology, it will be interesting to see whether motor skills start to become relatively inferior in future generations.

References

Gobry P.E. 2018. Montessori schools are exceptionally successful. So why aren’t there more of them? Washington, D.C.: (America, The Jesuit Review). Available from: https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society/2018/06/29/montessori-schools-are-exceptionally-successful-so-why-arent-there-more

Lillard A, Else-Quest NM. 2016. Evaluating Montessori Education. Virginia, USA: University of Virginia: (Science). Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6785327_Evaluating_Montessori_Education

Meinke H. 2019. Exploring the Pros and Cons of Montessori Education. Bloomington, Minnesota, USA: Rasmussen College. Available from: https://www.rasmussen.edu/degrees/education/blog/pros_cons_montessori_education/

Stephens A. 2016. The Benefits of Hand-Written Versus Digital Note-Taking in College lectures. Virginia, USA: James Madison University. (Lexia: Undergraduate Journal in Writing, Rhetoric & Technical Communication; vol. V). Available from: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1056&=&context=lexia&=&sei-redir=1&referer=https%253A%252F%252Fscholar.google.com%252Fscholar%253Fhl%253Den%2526as_sdt%253D0%25252C11%2526q%253Dbenefits%252Bof%252Btaking%252Bnotes%252Bby%252Bhand%252Bvs%252Bcomputer%2526btnG%253D#search=%22benefits%20taking%20notes%20by%20hand%20vs%20computer%22