The sunrays glide across the pond with grace as you take your weekend stroll. It is a bright, pleasant Sunday morning. As you kneel near the rose bushes, you close your eyes and take a deep breath — and the stench of your younger brother’s dirty socks envelop your senses instead. What can explain this phenomenon?

Parosmia is an olfactory dysfunction where the perceived quality of the odor is different from the actual odor stimulus. It is a condition that I have unfortunately experienced in the past, along with dysgeusia, altered or distorted taste sensation (Allis 20121). Olfactory dysfunctions are seldom a popular subject of concern, as the sense of smell is often considered a “hidden” sense. And surely, as the years have gone by since my condition, I had slowly forgotten to appreciate its presence as well. However, olfactory dysfunction has the ability to impair one’s gustatory functions, or taste, greatly as well due to the two senses being intimately linked. These two dysfunctions amount to abnormality in two of our five basic senses, and experiencing prolonged gustatory dysfunction can be especially dispiriting and frustrating. When we studied Escoffier’s passion to perfect his dishes, the imagery of one’s taste buds as “little keyholes into which our chewed food might fit” (Lehrer 2012, p. 582) led the frustrated middle schooler in me to recall the times I would picture fried chicken particles diving head first into my taste buds wishing to taste fried chicken again. I had merely caught the common cold, but it was no common cold. Three months after I had recovered from all other symptoms, I still smelled and tasted the funk of my middle school cafeteria with each ‘stimulus’ taste and smell, and I never understood the reason why.

Though it felt like it at each family dinner, I was not alone. Olfaction disorders affect up to 4 million people in the United States and have two known general causes. The first cause, usually treatable, is with a conductive component and includes nasal obstructions that anatomically block the olfactory cleft or its surrounding structures to disrupt nasal airflow. Nasal disorders such as allergic edema and chronic rhinosinusitis cause this (Allis 20121). The second, on the other hand, has a sensorineural component that concerns neural losses following upper respiratory infections. The decrease of airflow during a viral infection may result in permanent olfactory loss due to the apoptosis of olfactory neurons, or as recent research added, damage to higher cortical processing. Conditions that distort perception of taste and smell such as parosmia and dysgeusia are often linked to this cause as well (Allis 20121).

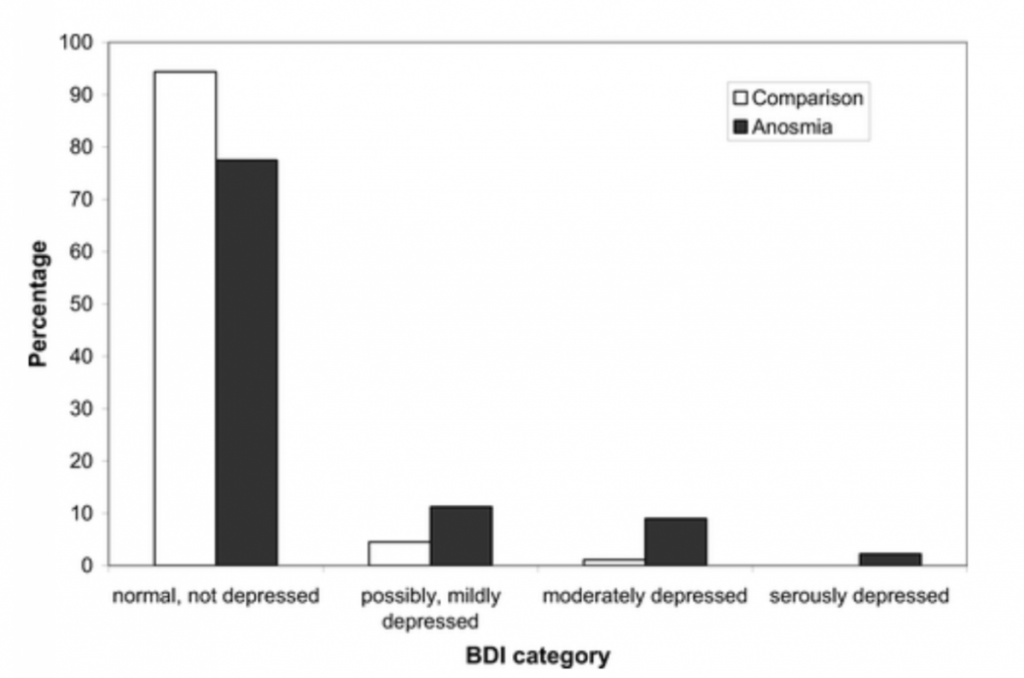

At the time I experienced parosmia and dysgeusia, I was shocked at how drastically it negatively impacted my quality of life. Olfactory and gustatory function impairment has proved to be a powerful way to generate fear of hazardous events, lower appetite, and decrease personal hygiene (Gopinath et al. 20113). In longterm cases, it can weaken social relationships and even trigger depression and anxiety symptoms (Sivam et al. 20164). To research the effects loss of smell has on emotional stability, a study in the Netherlands was conducted with members of the anosmia patient organization in 2008 to test the levels of depression of those with anosmia, a loss of smell, when compared to those with regular olfactory functions. 90 members of the organization were compared to a comparison group of with similar sex composition and an age average of 58.8 years. In a survey beforehand, 73% of those with anosmia stated that they experienced loss of taste along with their loss of smell, and a few among them also tasted and smelled foul tastes and smells that were not there. Furthermore, 77% of the members from the anosmia patient organization have been suffering from this condition for more than two years. Following the survey, the BDI, or the Beck Depression Inventory, was administered to the members and the comparison group to answer a questionnaire that is the most widely used instrument to detect depression. Though median scores for both the members and the comparison group were “normal, not depressed”, or 1.0, the scores were not normally distributed and people with anosmia scored significantly higher on the BDI (Smeets et al. 20095).

The results of the study surprised me and made me realize what a crucial part of our daily life it is to smell and taste things around me. When I lost the capability to smell and taste accurately, I felt isolated from the world I was living in because I was deprived of two of our five senses that connected me to the world, a feeling that the patients with anosmia in the study probably experienced as well. In hindsight, I was very lucky that my sense of smell and taste eventually returned after a few months, and it was a great reminder that I should definitely stop and smell the roses on my next walk.

Bibliography:

1. Allis TJ, Leopold DA. 2012. Smell and taste disorders. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 20(1):93–111.

2. Lehrer J. 2012. Proust Was a Neuroscientist. Prestonpans, Scotland: Canongate Books.

3. Gopinath B, Anstey KJ, Sue CM, Kifley A, Mitchell P. 2011. Olfactory impairment in older adults is associated with depressive symptoms and poorer quality of life scores. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 19(9):830–834..

4. Sivam A, Wroblewski KE, Alkorta-Aranburu G, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Pinto JM. 2016. Olfactory dysfunction in older adults is associated with feelings of depression and loneliness. Chem Senses. 41(4):293–299..

5. Smeets, Monique A. M., Veldhuizen, Maria G., Galle, Sara, Gouweloos, Juul, de Haan, Anne-Marie J. A., Vernooij, Jesse, Visscher, Floris, Kroeze, Jan H. 2009. A. Sense of Smell Disorder and Health-Related Quality of Life. US : American Psychological Association; [cited 2021 March 2] Available from: http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=e74e7fc8-5fdb-4c01-8030-7448af687a20%40sdc-v-sessmgr01&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#db=pdh&AN=2009-22297-007&anchor=c35.