In Molly Jobe’s presentation today, she proposed some ways to promote maternal-fetal attachment. These included Talk with Me Baby, Centering Pregnancy, and Kangaroo Care. All of these are very low cost and research has shown that they are very effective. In fact, Kangaroo Care, is much more effective than other more expensive/invasive options such as incubators. From a global perspective, I think these would be excellent interventions to promote as they are relatively simple, cheap, and effective! It would just require widespread education, and for Centering Pregnancy it would require some basic equipment like a scale and blood pressure cuff. I think its interesting to note that a form of Kangaroo Care is actually carried out in many cultures like in sub-Saharan Africa, where babies are carried most of the time snug on their mother’s back with kikwembes (cloth wraps). Funny how before new technologies were invented (like incubators and formula and C-sections that are now used extensively in many countries), people used more natural methods (like kangaroo care, breastfeeding, natural births) – and research is now showing these to actually have better outcomes.

Monthly Archives: November 2014

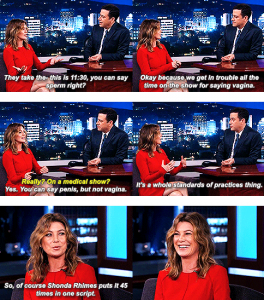

Sex Education and the Acknowledgement of Female Sexuality

On a recent episode of Jimmy Kimmel, actress Ellen Pompeo of Grey’s Anatomy fame commented on the fact that even on medically themed show, the word vagina is seen as inappropriate and borderline obscene. It’s this intrinsic stigma against the female body that must be considered when constructing sexual education programs. Most people are intimidated by the unknown, and the female body, especially in its sexuality, is largely unexplored. When educating young students about the mechanics of sex, there is no room to shy away from one half of the biological population. Providing honest, unbiased data is difficult when there is a significant lack of research into the specifics of the female sexual experience. This information gap, however, should not hinder open and honest sex education. It merely requires us as educators to acknowledge what we do not know and encourage healthy and safe exploration. We have taken the comfortable path regarding sex ed over the past couple of years, and clearly, it leaves much to be desired. It’s time to step outside the comfort zone, acknowledge women as the sexual beings they are, and provide students with the tools needed to have healthy sexual relations.

Community Mobilization

“Dr. Jim Kim, anthropologist, clinician, and former WHO advisor has commented that anthropologists have a long history of providing ‘moral witness to human suffering’. What is needed now, he argued, is ‘moral witness to human possibility'”.

The readings for this week on community mobilization for safe birth provide two different examples of how human possibility and morality can improve public health – in this case, maternal and child health.

The community-based participatory research study in the Dominican Republic found that both men and women were dissatisfied with the maternity services in the hospitals. While the Dominican Republic is a relatively developed nation, there are substantial socioeconomic inequalities. Although 97% of births occur in health facilities, an optimistic number compared to some other areas of the world, the MMR is high, at 150-160/100,000 live births. A main issue identified by the communities involved in the study is a delay in accessing care. The researchers aimed to determine why women delayed going to the hospital amidst complications.

The findings were unfortunate. The community recognized pregnancy as a vulnerable and fragile time for a woman. However, they did not receive adequate, compassionate care at health facilities. “No me hace caso” – “they pay no attention to me” – became a recurring theme throughout the study. Wait times for appointments and even surgeries were absurdly long, even though the commute was manageable. Doctors were not comforting women and their families when they were anxious. The women felt that nobody was there for them or taking care of them, and procedures and outcomes were not explained properly.

This project shows that when a team of researchers, professionals, community members, and hospital staff come together, a common goal can be reached. Since the maternity service providers have now been made aware of the dissatisfaction of the community, steps can be taken to improve the quality of care. It is unsettling that while the backbone of a potentially successful maternal health system exists, that something like staff attitudes have an impact on MMR. Hopefully, the future of maternal health services is bright in those communities.

In Humla, Nepal, a project was done by the PHASE Nepal foundation to change a harmful cultural practice – keeping a new mother and her baby in a cowshed after delivery for one month. This is very dangerous, given the high possibility of infection, in addition to uncomfortable living conditions. However, the researchers knew that changing engrained beliefs is difficult, and did not want to appear as judgmental outsiders. They came up with the idea to provide useful incentives – new clothes for the mother and baby – in exchange for a safer area for the mother and newborn to live postpartum. Another part of the initiative was increasing skilled birth attendance. The project had a successful outcome, with 50% of births being attended by skilled birth attendants and almost 100% of families accepting the clothing for safer postpartum living spaces.

This project demonstrates that changing a cultural belief is possible, when the community understands what the problems are and how to adhere to their beliefs in safer ways (i.e. separate room of the house dedicated to mother and baby, room restrictions, or a small guest house).

With the risk of sounding cultural insensitive, the underlying problems in both articles remind of me Sue Ellen Miller’s Ted Talk, when she said that women are “discriminated to death”. In both of these articles, we see that change is often needed in areas besides access to medicine and equipment. These initiatives both dealt with cultural issues, which with the right plan, can be altered to benefit not just mothers and infants, but the entire community.

Sustainability of the Behavior Change Initiative in Nepal

As with any intervention that includes a distribution of goods or service, I always bear in mind the sustainability of the project. Although a certain program may have many beneficial short term outcomes, how can we be sure that the program will sustain these outcomes? In the Nepal program that we read about for this week, the idea of distributing clothing to mothers who give birth in the presence of trained health workers was presented. Although the authors cited many incredible outcomes, including that fact that over half of all births in the region were attended by trained health workers, I wonder about the long-term effects of the program. The authors stated that a private donor was needed to fund the buying and distribution of the clothes. What will happen when, inevitably, that donor decides to stop funding the project? What if the NGO is unable to acquire sufficient funds to buy clothes for the mothers? I worry about how this project can be sustained for the near future.

The key to providing a sustainable project would be finding a different incentive to have mothers change their behaviors towards maternal health that could be implemented by community members rather than NGO workers.

Uruguay–Abortion Decriminalized, Now What?

In Kayley’s presentation a few weeks ago, we discussed all the different barriers to abortion. In some countries and states, abortion is legal, or decriminalized in Uruguay’s case, but not without barriers. Some barriers include limiting training for providers, cost, age requirements.

Yonah’s presentation regarding decriminalization of first trimester abortions in Uruguay made me think about what we sometimes take for granted here in the US. While much of our government here in the US and Georgia is trying to restrict women’s reproductive freedom, Uruguay seems to be going the opposite direction slowly. Barriers Yonah mentioned include requiring 4 visits for an abortion. I can’t remember if this was medical or surgical, though. In the US, it is typically 2, sometimes 3, visits–one or two for the procedure, one for a follow up. Although I am happy to see that it is decriminalized, it makes me sad to hear there are still barriers.

What should reproductive freedom fighter Uruguayans focus on next? Should they focus on expanding abortion services to a later gestation (second trimester)? OR should they focus on breaking down current barriers for this first trimester abortion? Obviously, real life has many shades of gray and is not an either/or situation. If I had to choose one main focus, I would probably focus on breaking down current barriers. Once a first trimester abortion becomes more of a surgical or medical procedure and less of a moral action, then maybe activists can begin to convince people that second trimester abortions can head the same way.

Here is a good short, less recent piece on Uruguay that I found: http://popdev.hampshire.edu/projects/dt/77

Community Mobilization

What actually improves health outcomes and services in the long-run? One huge way is through community mobilization. But how can this be carried out successfully? The PHASE project in Maila and Melchham in Nepal provides a great example. In 2008, women in Nepal were giving birth in cowsheds and then spending their first month postpartum there with their baby. This was due to cultural traditions that considered new mothers (and menstruating women) unclean, but considered cows to be holy and clean – so what better place for the new mother to reside? This is a great example of the tremendous impact culture and beliefs have on health practices. The two are integrated and can’t be dealt with separately. Anyhow, cowsheds led to high levels of infection and a very high maternal mortality rate, with the adjusted UN estimate 850/10,000 in 2007. The four PHASE health workers involved the community in their entire process. First, they went house to house getting to know the community and conducting surveys, and held community meetings and called together the Female Volunteer Health Workers who were trusted members of the community and thus could have a large impact. Once some of the key issues were identified, such as the cowsheds, much discussion was held among themselves, with the FVHWs, with the community, and looking at how other parts of Nepal had dealt with this issue. In the end, they decided to give women the incentive of a new set of clothes if they went to a primary care center to give birth and agreed not to live in the cowshed. This came about after many discussions with the community about alternatives for where the mother spent her first month postpartum, and accepted the variety of options proposed, such a lean-to, or one room in the house. Now, half of births there are attended by a skilled health worker and almost 100% agree not to live in a cowshed. This is tremendous change, and it happened from the level of the community, and thus will be sustainable. Imagine is the PHASE health workers had simply gone in without extensively consulting the community and set up a birthing center. Would it have been successful? I don’t think so. Likewise, I think this lesson needs to be applied to so many other projects in many parts of the world. Using, there is a story behind resistance to change, and this needs to be explored and worked with! I think this could even be very applicable to the situation with ebola in West Africa right now. Just as one example, if the initial perception was that white people were bringing in the disease, then how likely is it that people would go to them when they got sick?

Lack of Incentives for Health Personnel

http://http://www.spyghana.com/coalition-unpaid-nurses-midwives-threatens-court-action/

This is an example of the poor treatment that trained health care personnel receive, and the lack of infrastructure in place to provide for them adequately. Thoughts on how to solve this issue?

Birth in War Settings

How can birth outcomes be improved in regions plagued with sexual violence, mass killings, and low levels of security? In countries such as Liberia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), war has consumed the nations for past several years. Maternal mortality rates are among the highest in the world and many women are not able to seek medical care immediately after experiencing sexual and/or war-related violence. So many of the citizens in these countries have limited socioeconomic resources and therefore are unable to seek assistance in times of despair. Aiding those most in need in these countries should be a top priority in the field of maternal care.

Establishing clinics like in the Liberia case study seems to be a very promising solution, however, I worry about the fees placed by Ruth on her patients. I understand the need to provide income to sustain the clinic and supplies, but I worry that many individuals, especially in times of war, would not be able to afford any type of medical care. Would there be any effective way of running a clinic like Ruth’s without having to charge patients with a fee for goods and services?

Role of Mobile Clinics

We’ve touched on utilizing mobile clinics a few times in the course. For the most part, we discussed it in a US context, but this could hold true for other areas of the world that have the quality of infrastructure that is required for an automobile.

In Beatrice’s presentation, we talked about utilizing mobile clinics on the reservation for American Indians. The wide and vast acres of land in AZ may require providers to meet women in their location for prenatal visits. An Emory alumna once told me that she likes to “meet patients where they’re at”. She meant this in terms of knowledge about their health, but I think this is equally as important in the literal sense. In Eric’s presentation of urban vs. rural care, we saw that mobile clinics can be helpful as well. I believe the example we saw was primary care provided to a rural W. VA community. In our MCH Safe Motherhood Malawi example, it was important for the nurse to gather in the village so the women could ask questions. Another example of mobile clinics–my best friend from college does breast screenings on a bus that also provides mammograms to women in 4 boroughs of NYC. In all these cases, you are bringing necessary care to the people that need it.

With respect to birth, I think prenatal visits are completely feasible and realistic for these American Indian populations or anyone else who may live in a very rural area. Similar to what we saw in Eric’s video, the visits can include disbursement of medication like prenatal vitamins and such. Mammogram and screening type appointments are also appropriate. What is the solution, though, when a woman gets further along in her pregnancy? What if complications occur between visits? Whose responsibility is this/shoulders does this fall on? In our society of finger-pointing, I think having mobile clinics can actually be very risky. I would hate to see the provider saying s/he left the woman in good condition and the woman saying why didn’t s/he catch this problem when s/he saw me? Also, what if the mobile clinic is bringing important medications to people and doesn’t make it out to the community for some reason? That can be life-threatening. I know IHS currently only collaborates with certain pharmacies, but perhaps getting a contract with a company like Express Scripts who delivers to the door might help and decrease gaps in medication.

Obviously, the best idea would be to build a clinic in these communities and convince healthcare providers to be there 2-3 or even 5 days a week, but what can we do in the interim that is not so risky? And in the interim with our mobile clinic prenatal visits, what would happen when it comes time for a woman to deliver? I’d like to see what people think out there, because I have been contemplating on this for weeks now and still haven’t brainstormed of any good ideas.

Training and Incentives

Like we’ve discussed in class, the terms “midwife” or “skilled birth attendant” mean different things in different cultures. They differ in terms of levels of education, authority and skill. I thought about having it mandated that all midwives worldwide have a certain skill and education level, but then I thought about the midwives and skilled birth attendants in places like Mali and how Monique was one of the only trained midwives in her location. Besides not having the infrastructure to train these individuals, I thought about wars and other obstacles that may prevent training or would make them reluctant to even go through the training process. From the case study that was done in Liberia, one of the issues that was mentioned was a shortage of midwives as well as a shortage of doctors. In cases where there is a shortage of midwives and other health professionals what are the options left for people who need medical care? and how can this shortage problem be solved? Nowadays in a lot of African countries, individuals receive their training in foreign countries and continue to practice in the country where they received training. They usually leave with the intention of returning but the incentives/benefits of having these degrees and certificates in most of these countries do not reflect their level of training. This summer in Nigeria, a lot of the doctors went on strike because they were not receiving their salaries. Like we also discussed in class, rural areas are less likely to be staffed with TBAs and TTMs because of distance and other factors. People would be reluctant to live so far from the city. I know for rural northern Nigeria, it was difficult for the National Primary Health Care development center to gather volunteers and midwives to relocate there. In addition to training more midwives and healthcare professionals, how can conditions in these rural locations be modified to make living easier so that these trained individuals would choose to stay.