Introduction

One Sunday I was in worship at Christ United Methodist Church in Franklin, TN watching our children perform the musical, “Moses and the Freedom Fanatics”. I wasn’t in the pews, but watching from the back until it was time for my then six-year-old daughter and I to perform the second plague from Exodus 7:25-8:15 in “The Dance of the Frogs.”

Later I began to reflect on how the very sanitized ways we begin exposing children to violent stories in the Bible don’t change all that much when we become adults. We may read past them because they make us uncomfortable, sometimes we dismiss them as not historically accurate or because most (though certainly not all) of these stories occur in the Old Testament. In some places in the church, we may even read these biblical stories and conclude that we are justified in committing acts of violence.

Violent episodes in the Bible are part of a larger story being told about the relationship between God and the world. However, in a world of action movies and 24-hour cable news, violent incidents tend to stand out more than other, arguably more important, aspects of the text. Most churches require pastors to have education that includes training in biblical scholarship, so we as pastors can and must do a better job of leading our people in deep engagement with scripture. This is not only for the sake of knowing these stories better, but so that our communities can be empowered to actively interpret scripture themselves and incorporate it into their ethical decision making.

In “Encountering Violent Texts in Scripture: A Study in Communal Hermeneutics,” I explore how pastors trained in biblical scholarship can expose lay persons to careful, accessible exegesis, focusing on putting a biblical text in context and exploring relevant features of a text can strengthen a congregation’s confidence in their ability to do the work of interpretation as a community.

Project Design

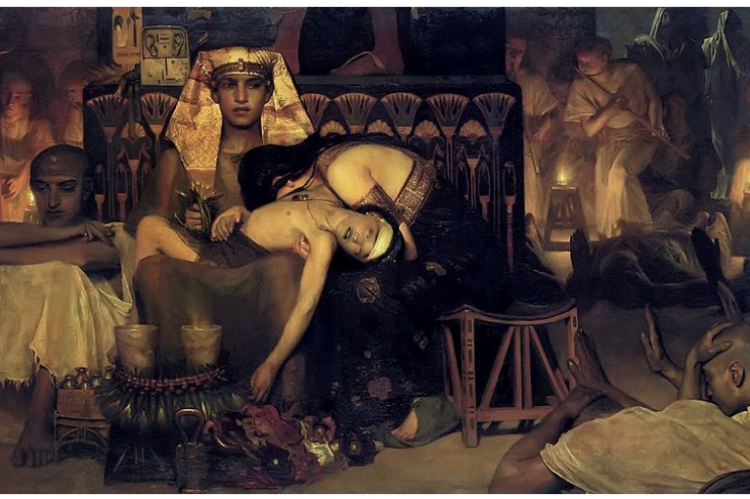

In the Fall of 2016 at Christ UMC, we combined several adult Sunday School classes for four sessions. Together we explored a sequence of violent events in Exodus, where first God, then humans, become violent actors. These are stories most people of faith know, but many modern people experience them first as films like The Ten Commandments and The Prince of Egypt, meaning that movies are our “text,” rather than the source material in Exodus. Over the four sessions we explored pericopes from Exodus 11 through 17, covering the death of the firstborn (Exodus 11:1-10 and 12:21-42), the parting of the Sea (Exodus 14:1-31), the Song of Moses (Exodus 15:1-19), and the battle with Amalek on the way to Sinai (Exodus 17:8-16).

In each session we defined violence as “physical, emotional, or psychological harm done to a person by an individual (or individuals), institution, or structure that results in injury, oppression, or death.1 We then identified three key questions that would guide our approach in each session: What is the Bible? How is the Bible authoritative for us? And how does the Bible participate in our process of making ethical decisions? We also noted that we would not solve these big questions once and for all, but that they would guide our study of the text and our work of communal interpretation.

In preparing these sessions I spent several months exploring these seven chapters of Exodus, aided by work from scholars such as Walter Brueggemann2, William H.C. Propp3, Jerome F.D. Creach4, and Millard Lind5. Since there are many different ways to approach these stories and many different features in them that can be explored, I wanted to keep a tight focus on exposing the people to, but no overwhelming them with, scholarly exegesis. The purpose was for them to feel more confident in interpreting these texts in community and applying their interpretation to issues of violence in our world. I concluded that this would be best served by focusing on putting the text in context and highlighting features in the text that were relevant to the modern issues we were considering.

Text in Context

In this study, one way of putting the text in context was to talk about how the violent episodes in Exodus all take place to advance the “covenantal liberation” of Israel. Brueggemann calls covenantal liberation the “core claim” of Exodus: the Hebrew slaves are liberated from oppression not only for their own sake, but so that they live as a people in covenant with YHWH. This community’s liturgical remembrance of what their God has done for them throughout the generations continually announces alternative possibilities to the oppressive structures of the world.6 The celebration of the Passover and the Feast of the Unleavened bread is “not just a historical commemoration but an actual reenactment” of what first occurred in Egypt.7 Liturgical remembrance is both memory of what has happened in the past and identity formation for the present community.8

Each session also emphasized the presence of very specific liturgical instruction that surrounds each violent act. If one was to determine which aspects of the text are the most important solely by counting words, liturgy would win in a landslide. Due to this word count ratio, Carol Meyers argues that the passages of liturgical instruction formed the way the narratives of violence were shaped.9 Moses’ first request to Pharaoh was for the Hebrews to have three days to go and worship YHWH (Exod. 5:3), and the request for universal manumission only comes after Pharaoh refuses (Exod. 6:6). Worship precedes freedom. Freedom is not an end unto itself, but Israel is freed for the larger purpose of entering into a covenant with YHWH and living as a people whose communal life demonstrates a drastic alternative to those of other societies. Their way of being community demonstrates to the world who their god is.10

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ab/1872_Lawrence_Alma-Tadema_-_Death_of_the_Pharaoh_Firstborn_son.jpg

Relevant Features of the Text

The other main theme in the exegetical presentations was highlighting features of the text that are relevant to the study. In several sessions we also explored the choices made in translating Hebrew to English (NRSV) to ask whether the actions of YHWH and humans are so fundamentally different it is difficult, if not impossible, to justify humans engaging in violent acts because “God did it in the Bible.” One example of this exploration is seen in the use of the Hebrew word for hand, yad. Many different characters are described as having physical or metaphorical hands: Moses, Aaron, “the enemy” (Exod. 15:9, specifically Pharaoh and his army, more broadly all of Israel’s enemies), and YHWH. Yet of all the “hand” references in the text, only YHWH’s yad is modified by the adjective chazaq, or “mighty” (Exod. 3:19; 6:1; 13:9; 32:11). Chazaq is also used to describe the wind that YHWH uses to part the Sea (Exod. 10:19), and the loud trumpet blast at Sinai (Exod. 16:9). Everyone has hands, only YHWH’s is “mighty,” suggesting a fundamental difference in the way YHWH acts in the story and how humans act, which leads modern communities to a certain interpretive caution. Just because God is portrayed as doing something in a text does not automatically mean that modern human communities have license to act in similar ways.

Small Group Discussions

What people got from these exegetical “deep dives” was revealed in small group discussion during the final fifteen minutes of each session, in surveys conducted at the beginning of the first session and the end of the last, and in follow-up interviews.

In the context of these discussions, I came to realize the necessity of balancing both the personal challenges that a scriptural text can give to individuals with any larger claims it may make on our public or communal ethics. Focusing too much on the public implications can allow individuals to ignore the personal challenges, simply expressing their opinions on what others should do. Likewise, focusing only on personal challenges does not allow for people to reflect on how people of faith should influence public life. This last part is particularly important for people of faith who are voting citizens in democracies where they can influence the actions of elected leaders.

This balance, while not achieved in every session, worked fairly well in some. In Session 1 we looked at the death of the firstborn of Egypt, where God acts violently on behalf of an oppressed group, but those who are harmed by the violent actions are non-combatants. The small groups considered how we might use this text in thinking about whether violent acts in defense of innocent people are acceptable when other innocent people might or even are guaranteed to be hurt. The example we used is the United States using bombs delivered via drone to take out leaders of the Islamic State, who are responsible for horrific war crimes, even though those leaders are residing among civilian populations who would be “collateral damage” of the drone strike.

The groups reported that, among other things, they agreed that it was difficult to draw a straight line between God’s violent actions on behalf of an oppressed people and our own. When human beings engage in violent action, they are somehow “playing God” in deciding who is harmed and who is not, even though such action may be the “lesser evil” where no good option, inaction being complicity in oppression, is on the table. One participant pointed out that being a “non-combatant” does not necessarily mean that a person is innocent. As was mentioned above, the children of Egypt benefited from the structural oppression of Hebrew slaves. They as individuals may not have actively participated in perpetuating the slave system, though it is likely many of them would have later in adulthood. Several groups also reflected that human beings are “tribal” and prone to conflict, and they believed Jesus came along later to redefine how human beings understand what constitutes our “tribe.”

Post Course Surveys and Interviews

At the beginning of the first session and the end of the fourth, class participants were asked to complete brief surveys, numerically indicating their confidence in forming an opinion on what a biblical text means for themselves and expressing that opinion to others. Participants were also asked to indicate how often they took scripture into account when making ethical decisions for themselves and for the community. Lastly, they were asked to state their beliefs about violence in scripture and violence in the world, with the opportunity to write in comments. Asking about people’s perceived ability to form and opinion on what a biblical text means, on a scale of 1 to 5, the average on the pre-course survey was 2.93, and on the post course survey was 3.15. Likewise, the people’s confidence in expressing their views on what a text means went from 2.55 to 3.4. While these questions are inherently subjective, expressing their feelings numerically shows that the method met with some success.

Several participants consented to post-study interviews. Here we see one participant, “Melinda”, reflect on her experience and her belief in the importance of doing scriptural interpretation in community.

But just because people feel more confident in their ability to interpret scripture does not mean they are no longer in need of pastoral guidance. As Rein Bos argues about sermons, which I would argue also applies to teaching, “when a sermon has nothing more or nothing else to offer than a kind of popularized scholarly exegesis, it fails completely the task and calling of preaching.”11 There must be some end goal in mind. Without expecting everyone to come to the exact same conclusion, a pastor must focus on some basic values they want to impart in their teaching. Reflecting on people’s feedback is essential, especially when we are attempting to connect people’s faith journeys to the way they relate to the world around them.

What’s Next

Going forward I would like to see how this method of exploring scripture with lay persons is received in different cultural contexts. A congregation with mostly affluent, educated white people is very receptive to exegetical deep dives, but what shape would these sessions take in rural contexts, urban contexts where gang violence, not war, would be the primary violence issue on people’s minds? I would also like to see how this method plays out in non-American settings. I have had conversations with a colleague who is a missionary educating clergy in Central America about doing this study with their students. I will need to improve my Spanish quite a bit for that to come to fruition.

These types of studies and conversations are important ways to deepen discipleship and connect people’s faith with the issues in the world around them. Pastors should not be afraid to expose lay persons to scholarly exegesis, because doing so will empower them to be readers and interpreters of scripture in community.

(Big thanks to Professors Joel LeMon and Brent Strawn for their guidance and support for this project.)

Bibliography

- Eric A. Seibert, The Violence of Scripture: Overcoming the Old Testament’s Troubling Legacy (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012) 9.

- Brueggemann, Walter. The Book of Exodus: Introduction, Commentary, and Reflections. in The New Interpreter’s Bible Commentary, vol 1. Nashville: Abingdon Press. 1994.

- Propp, William H.C. Exodus 1-18: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. The Anchor Bible vol. 2. New York: Doubleday. 1999.

- Creach, Jerome F.D. Violence in Scripture (part of Interpretation: Resources for the Use of Scripture series). Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. 2013.

- Lind, Millard C. Yahweh is a Warrior: The Theology of Warfare in Ancient Israel. Scottsdale, PA: Herald Press. 1980.

- Brueggemann, NIB, 1:771.

- Propp, Exodus, 1:427-8.

- Lind, 54.

- Meyers, Exodus, 70.

- See Seibert’s introduction to The Violence of Scripture, particularly pages 11-12, also Brueggemann, NIB, 1:683-686.

- Bos, Rein. We Have Heard that God is with You: Preaching the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans. 2008. p. 108.