Oneness

with Christ, Each Other, and All the World

in Eucharist and Mission

“By Your Spirit make us one with Christ, one with each other, and one in ministry to all the world, until Christ comes in final victory and we feast at his heavenly banquet.” In the concluding prayers of the Great Thanksgiving discover that the Eucharist is more than solely remembering the salvific work of Jesus Christ. It also serves as an inspiration for the congregation Church to be sent to our local community and world in mission.

Historical Background of the Eucharist and Missional Community

What signifies an authentic Eucharistic Missional community? To begin this discovery, I look beyond inherited institutional ecclesial and ecclesiastical traditions and at the practices of the early church. The first Christian gatherings took place in homes. In the home the scriptures were read, stories were told, encouragement and exhortation practiced, and meals were shared. It is among these early meals that the initial glimpses of New Testament Eucharistic practices are observed. Whereas someone set apart for the purposes and benefits of others performed institutional rituals in temple Judaism, the early Christian meal was an act of koinonia, the participation of all gathered sharing something in common. Though worship would have taken place in the temple, koinonia took place in homes. As Ben Witherington states:

It is interesting, however, that the worship is said to take place in the temple, but the fellowship and sharing in common, in the homes. This suggests a meal context for the early celebration of the Lord’s Supper but perhaps not an ordinary early Jewish worship context, for the reference to the breaking of bread and prayer can be read to mean the normal things that happened at an early Jewish meal.

These traditional approaches have painted a picture of the Eucharist solely as a ritualistic act of Jewish origin and have formed the liturgy surrounding the act of the ritual. Though the passage in verses 23-26 clearly form the words of institution, the Apostle Paul also is noting that the death of Christ must be central to the meal. This also must be central to understanding the missional aspects of the meal. Richard Hays states:

The proclamation of the Lord’s death occurs not just in preaching that accompanies the meal; rather, the community’s sharing in the broken bread and the outpoured wine is itself an act of proclamation, an enacted parable that figures forth the death of Jesus ‘for us’ and the community’s common participation in the benefits of that death. The problem is not that they are failing to say the right words but that their enactment of the word is deficient: their self-serving actions obscure the meaning of the Supper so thoroughly that it no longer points to Christ’s death.

Therefore, Hays is stating that true Eucharistic community, influenced by I Corinthians 11: 23-26, is not defined solely by participating in the meal. Rather, it also includes the proclamation of the salvific work of Christ to those in and outside of the community. This alone is the foundation of mission and oneness in Eucharistic community.

Beyond the inherited ritual of the Jewish sect, Paul F. Bradshaw notes that there are two recent principle trends in the search for Eucharistic origins. The two approaches lend themselves to researching the fellowship meal practices of the early church within their social contexts. Speaking of these trends, Bradshaw states:

The theme of gathering in homes for fellowship meals is a common thread in both areas of recent scholarship. In the Greco-Roman world, in the midst of Hellenization, it was the norm of the society to gather for fellowship meals and celebration. A typical evening would have a host, guests of honor, and servants attending to the gathering. Typically following the eating ritual drinking parties would take place and the celebration would continue.

Central to the new ideals of fellowship meals was the teachings and example of Jesus Christ. Where once these meals were constituted of only like-minded people of similar societal and social status, in Christ these cultural barriers were broken down and redefined to be inclusive of all who professed Christ. Therefore, the fellowship meal inherited ideals and identities to that of the mind and example of Christ. Christ was brought into the center of the frequent tradition of fellowship meals. The presence of Christ within the community gathered fostered ongoing transformation which in turn established a process of growing in grace and mission.

As Witherington states:

The Christian meal was to depict the radical leveling that the kerygma proclaimed – whoever would lead must take on the role of a servant, and all should be served equally. This social leveling was meant to make clear that there was true equality in the body of Christ All were equal in the eyes of the Lord, and they should also be viewed that way by Christians, leading to equal hospitality towards all.

A transformation took place on both the individual and communal levels. For the individual, there was a social leveling that took place. Over time, as individuals began to further identify with the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, they transformed from selfishness offer hospitality to those in need. Thus, there was a oneness in mission to be in service others.

Early Wesleyan Theological Convictions

Early Wesleyan theological convictions surrounding the Eucharist are found in the writings of John and Charles Wesley. Notable to John Wesley’s theology of the Eucharist is Daniel Brevint’s The Christian Sacrament and Sacrifice. This work was so influential to Wesley that the content formed the preface to Hymns on the Lord’s Supper. In his monumental work Brevint declares:

The main intention of Christ was not here to propose a bare image of his passion once suffered, in order to a bare remembrance; but, over and above, to enrich this memorial with such an effectual and real presence of continuing atone-ment and strength, as may both evidently set forth Christ Himself crucified before our eyes, (Gal iii. 1,) and invite us to his sacrifice, not as done and gone many years since, but, as to expiating grace and mercy, still lasting, still new, still the same that it was when it was first offered for us.

The above statement embodies a generalized central Eucharistic focus for Wesley: God is present at the table actively extending grace to communicants. This grace, which according to Brevint, is still lasting, still new, and still the same.

As Charles Wesley penned:

In the Presence of the meanest Things

While all from Thee the Virtue springs

The most stupendous Works are wrought.

The stupendous work that the early Methodists desired to experience was the inward work of the Holy Spirit that brought forth assurance of their faith. Thus, this stupendous work is inclusive of the totality of the life of God born into the souls of persons, therefore, making them disciples of Jesus Christ. For these pioneers of the movement they experienced the work of Jesus on the cross, pouring out himself for the sins of the world, and were humbled to receive this gift of grace. It was effective to assure them of their faith.

Stevick explains:

While Wesley holds that God works through the bread and wine, he shows little interest in what may or may not happen to the elements in the Eucharistic meal. The bread and wine are essential conveyances of divine life, but the wonder is that they are so while remaining bread and wine (57:2. 7-8). Such transformation as does take place in the sacrament happens in the vital encounter between Christ and his people. Wesley asks, ‘Come and change me Nature’ (87: 7.3)

Therefore, every occasion one received the sacrament it could be experienced as an opportunity to receive from God, to grow in grace, and to be assured of one’s salvation. In the beloved hymn ‘O the Depth of Love Divine’ it is expressed that communion with God is conveyed by bread and wine:

O the depth of love divine, th’unfathomable grace!

Who shall say how bread and wine God into us conveys!

How the bread His flesh imparts, how the wine transmits His blood,

Fills His faithful people’s hearts with all the life of God!

The Hymns on the Lord’s Supper give a glimpse into the underlying theology of the early movement. These hymns are not only a poetic portrayal of a deep theology of the Eucharist. In addition, the hymns provide a scenic view of the cross – of Christ’s real presence among them.

Wesley’s Hymns on the Lord’s Supper also involves the systematic approach to one’s personal experience of conversion, assurance, and celebration of final and eternal communion with God.

From Inward Assurance to Outward Mission:

the United Methodist Great Thanksgiving

Thousands of years have passed since these early fellowship meals and hundreds since the early formation of Wesley’s theology. However, the Christian church remains connected to the basic gestures and prayers of them. The United Methodist Book of Worship states:

The Thanksgiving and Communion, commonly called the Lord’s Supper or Holy Communion, is a Christian adaptation of Jewish worship at family meal tables – as Jesus and his disciples ate together during his preaching and teaching ministry, as Jesus transformed it when he instituted the Lord’s Supper on the night before his death, and as his disciples experienced it in the breaking of bread with their risen Lord (Luke 24: 30-35; John 21:13).

The United Methodist Great Thanksgiving also contains examples of Jesus’ missional engagement among those whom he served: “He healed the sick, fed the hungry, and ate with sinners.” The United Methodist Book of Worship contains twenty approved liturgies for use during worship services that celebrate Holy Communion. Within these liturgical texts one is prompted to remember the mission of God. In the Great Thanksgiving for Advent we read: “Your own Son came among us as a servant, to be Emmanuel, your presence with us. He humbled himself in obedience to your will and freely accepted death on a cross.”

In addition, in the United Methodist Membership vows new members vow to “faithfully participate in its ministries by their prayers, presence, gifts, service, and witness.” In each of these areas of commitment there is a missional component. Therefore, the members of the Lighthouse Church congregation vow themselves to faithfully participate in the ministries of the church in ways that are missional. At the celebration of the Eucharist, a prayer is made emphasizing the missional orientation of Methodist worship.

The theological convictions for this research stem from the oneness prayer in the Great Thanksgiving: “By your Spirit, make us one with Christ, one with each other, and one in ministry to all the world until Christ comes in final victory and we feast at his heavenly banquet.” Dr. Ed Phillips provides context to when this prayer was added to the United Methodist Great Thanksgiving:

That became part of the truly official service of Word and Table by action of the 1988 General Conference that approved the UM Hymnal and the ritual it would contain. However, it was adopted as a part of the unofficial, but recommended text, The Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper: An Alternative Text (1972). It circulated around in various photocopied forms the year before that.

The Christian community is to be one with Christ in his life, death, and resurrection, is to be one with each other, and one engaging in mission and ministry to all the world. Numerous biblical references speak of unity. However, we must look at the totality of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ to understand oneness with Christ. Philippians speaks to the character of Christ in his self-emptying:

Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others. In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death – even death on a cross!

To be one with Christ is to have the same mindset of Christ. This is the theological reality to which we are called. We are to be humble servants who value others above ourselves. We are to look to the interests and needs of others and make them a priority. This requires ongoing self-emptying.

The Church is also to be one with each other in an authentic Christian community. For this theological conviction I look back to the earliest gatherings of Christians. These gatherings took place in homes where scripture was shared, stories told, and meals were shared. The early meals of the Eucharist were far different than the typical customs in our post-Constantinian era. Whereas we often experience Holy Communion by receiving a small consecrated piece of bread and a small cup of juice, the early Christians shared meals of koinonia. By bringing together what they had to offer, they were one with each other in care and fellowship.

There is the theological conviction that through authentic koinonia with one another we are sent from the table – or from the Eucharistic gathering – to be one in ministry to all the world. As we are fed the bread and the cup, so we are to feed the world with the same bread and same cup, ever becoming the hands, feet, and body of Christ. This is where the missional aspect of the Eucharistic liturgy arises. In an earlier paragraph of the United Methodist Great Thanksgiving we read these words: “He healed the sick, fed the hungry, and ate with sinners.” Throughout the liturgy, we are reminded not only of God’s continuing sustaining power of God’s people; but of Christ’s incarnate ministry among the least of these. These words inspire those participating to recall the ministry of Christ, thus transforming the church to be sent from the table.

Missional Contextualization of the Communion Liturgy

Central to the celebration of the Eucharist in the United Methodist tradition is the use of the approved liturgies provided in the United Methodist Book of Worship. In the section entitled An Order for Sunday Worship, instructions are given to the one presiding over the meal:

As Jesus gave thanks over (blessed) the bread and cup, so do the pastor and people. This prayer is led by the pastor appointed to that congregation and authorized by the bishop to administer the sacraments there, or by some other ordained elder. The pastor stands behind the Lord’s table, the people also standing. After an introductory dialogue between the pastor and people, the pastor gives thanks appropriate to the occasion, remembering God’s acts of salvation and the institution of the Lord’s Supper, and invokes the present work of the Holy Spirit, concluding with praise to the Trinity.

The Great Thanksgiving liturgies in the United Methodist Book of Worship correspond to the liturgical year. Each of these versions of the Great Thanksgiving contains the prayer: “By your spirit make us one with Christ, one with each other, and one in ministry to all the world, until Christ comes in victory and we feast at his heavenly banquet.” This missional prayer is one that is used in all seasons and during all celebrations of the Eucharist of the Lighthouse United Methodist Church.

By contextualizing the Great Thanksgiving, the presider can help focus the congregation’s attention on local missional needs on an ongoing basis. Being one in ministry to all the world is large in scope. Being keen on avenues that the congregation can be in ministry outside of the walls of the building, the prayer can be altered to include those avenues of ministry. This not only provides a practical way to share the missions of the local congregation, but it also evokes the imagination of leaving the table to be the hands, feet, and body of Christ as a Eucharistic missional community.

Practical Examples of Contextualization

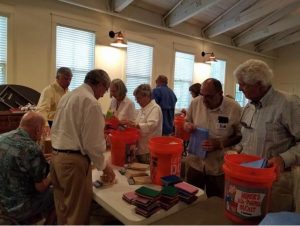

The weekend of August 26, 2017 Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Texas. As the news was reporting images of devastation, there were considerable calls from our local congregation about how we could help. Also, the Florida Annual Conference missions team were deliberating on the best way for the conference to respond. A challenge was issued by the Annual Conference for local churches to conduct a bucket brigade and fill flood relief buckets with needed supplies. In addition, hygiene kits were requested.

The Lighthouse Church took up this challenge on Sunday, September 3, 2017, and included the need in the Great Thanksgiving. The prayer of unity and mission was changed to embody the current need to respond to this natural phenomenon:

By your spirit make us one with Christ, one with each other, and one in ministry to all the world – especially those who have been and will be affected in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey. Give us hearts for our brothers and sisters in Texas and help us to generously respond by providing flood relief buckets and hygiene kits. May we always respond generously in times of need, until Christ comes in final victory and we feast at his heavenly banquet.

Following the celebration of the Eucharist, we shared the details of the bucket brigade project, connecting it with our congregation’s reputation of being known as a people who put action with their prayers. Within the following week both funds were raised and supplies were purchased. Some of the congregation put together their own relief supplies. On September 10, following the morning worship service, the congregation remained to organize and ready the buckets and other supplies.

Not long after the landfall of Hurricane Harvey the State of Florida had our own emergency. Hurricane Irma headed directly through the state leaving a path of devastation in Central Florida. This occurred one week before World Communion Sunday. Nevertheless, our plans changed concerning the storm relief project for Texas. A call was issued by the Annual Conference to keep the flood buckets and hygiene kits in our local communities and to respond by giving them to designated relief centers. Also, a call was issued by our Bishop to receive funds designated for Hurricane Irma relief in the State of Florida. On World Communion Sunday during the communion liturgy, the oneness prayer was again placed into context:

By your spirit make us one with Christ, one with each other, and one in ministry to all the world – especially those who are our neighbors and have been affected in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma. Let us be the hands, feet, and body of Christ all over our state. Give us your grace to respond in generosity to be one in ministry with our sisters and brothers. May we always respond generously in times of need, until Christ comes in final victory and we feast at his heavenly banquet.

Over the next week a local mission team was formed who collected and delivered storm relief supplies to a distribution site in Alva, Florida. In addition, over 40,000 dollars was contributed for the special conference fund. Though different in form, the liturgy and practice of Holy Communion contributed to persons being inspired to become a part of missional endeavors to alleviate suffering following these devastating storms.

In the forthcoming and lived chapters of this project I am incorporating my theology of revelation. I define my theology of revelation as “God’s unfolding and liberating story being told. It has been told from the God’s infinite beginning of time. It requires the openness of the heart and the quietness of the soul to hear and both digest the past chapters and the next chapters.”

I have begun to utilize this personal theology in my local context as God reveals next steps. Based on the initial impact considering how the Eucharist inspires the Church to be in mission, God’s liberating story is being told not only through the missional efforts of the church but through the expanding of our minds and actions as we pray the oneness prayer on an ongoing basis.

Both now and in the future – O God:

Make us one with Christ,

one with each other,

and one in ministry to all the world.

Recommended Resources:

Bowmer, John C. The Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper in Early Methodism. London: Dacre Press, 1951.

Bosch, David J. Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission. Twentieth anniversary edition. American Society of Missiology Series ; No. 16. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2016.

Brevint, Daniel, The Christian sacrament and sacrifice: by way of discourse, meditation, and prayer upon the nature, parts, and blessings, of the Holy Communion. Missale romanum; or, Depth and mystery of Roman mass: laid open and explained, for the use of both reformed and un-reformed Christians. Oxford, J. Vincent; London, Hatchard and Son, 1847.

Felton, Gayle Carlton. This Holy Mystery: A United Methodist Understanding of Holy Communion. Nashville, TN: Discipleship Resources, 2005.

Fulkerson, Mary McClintock. Places of Redemption: Theology for a Worldly Church. Oxford; NY: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Hays, Richard. Interpretation: First Corinthians. Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1997.

Koenig, John. The Feast of the World’s Redemption: Eucharistic Origins and Christian Mission. Harrisburg, PA.: Trinity Press International, 2000.

Newbigin, Lesslie. The Open Secret: An Introduction to the Theology of Mission. Revised edition.. London: SPCK, 1995.

Stevick, Daniel B. The Altar’s Fire: Charles Wesley’s ’Hymns on the Lord’s Supper, 1745’ : Introduction and Comment. Peterbrough: Epworth, 2004.

Stookey, Laurence Hull. Eucharist: Christ’s Feast with the Church. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1993.

United Methodist Church. The United Methodist Hymnal. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1989.

United Methodist Church. The United Methodist Book of Worship. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1992.

White, James F. The Sacraments in Protestant Practice and Faith. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1999.

Williams, Matthew M. A Personal Theology of Revelation. 2017.

Witherington III, Ben. Making a Meal of It: Rethinking the Theology of the Lord’s Supper. Waco, TX., Waco: Baylor University Press, 2007.