Laying down your life means making your own faith and doubt, hope and despair, joy and sadness, courage and fear available to others as ways of getting in touch with the Lord of life.

—Henri Nouwen

INSPIRATION

On a warm Wednesday evening, June 17, 2015, in downtown Charleston, a small group gathered for an evening bible study at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. The church is reverently known as Mother Emanuel for its historic prominence in African-American and South Carolina history. As the bible study came to a close, twenty-one-year-old self-identified White supremacist Dylann Roof opened fire on the church group, killing nine people, including their pastor and State Senator, Rev. Clementa Pinckney. Racial tension and random gun violence had jolted sleepy American towns to deadly nightmares before, but this time the evil violence shattered the silent sanctity of a church. Charleston, known as the Holy City for its plethora of historic churches, was terrorized to its core. The consequences of violence reached the sanctuary of not only Emanuel AME, but every sanctuary of the greater Charleston community. As the entire nation grieved the deadly racial terrorism, pastors in the Charleston community had a particular task before them: to offer pastoral care to local congregations in crisis, who no longer felt safe in God’s sanctuary.

Source: Charlestowne Stained Glass, Untitled, Stained Glass Panels, 2016, The Mother Emanuel Tribute at Charleston International Airport, SC. The glass studio created the two-part panel with nine doves to represent each slain bible study participant of Emanuel AME.

DILEMMA: PREACHING IN THE AFTERMATH OF COMMUNAL TRAUMA

While every pastor faces unique needs within their local congregation—needs of individuals, families, and the surrounding community—a tragic and traumatic event like the massacre of the Emanuel Nine calls for a specific pastoral response. The violence that breached the sanctuary of Mother Emanuel church was a communal trauma impacting congregations across the entire community. In the aftermath of such a trauma, some parishioners may seek individual pastoral counseling or care, but most members will look to the Sunday pulpit for direction to face tragedy and find God’s comfort. Pastors experience their own stress, grief, and inadequacy, as their congregation looks to them to offer a word of hope and healing in the midst of the trauma and what appears to be a senseless tragedy. What is the best method of pastoral preaching to care for congregations experiencing a traumatic communal event?

Source: David Goldman, “Bridge as Unity”, 2015, Photograph, The Mother Emanuel Tribute, Charleston International Airport, SC. Taken on the Ravenel Bridge just days after the shooting. Goldman hoped to capture the unity displayed as thousands gathered to mourn and pray for the Emanuel Nine.

PROPOSED SOLUTION: INTEGRATING REFLEXIVE PRACTICE INTO SERMON WRITING

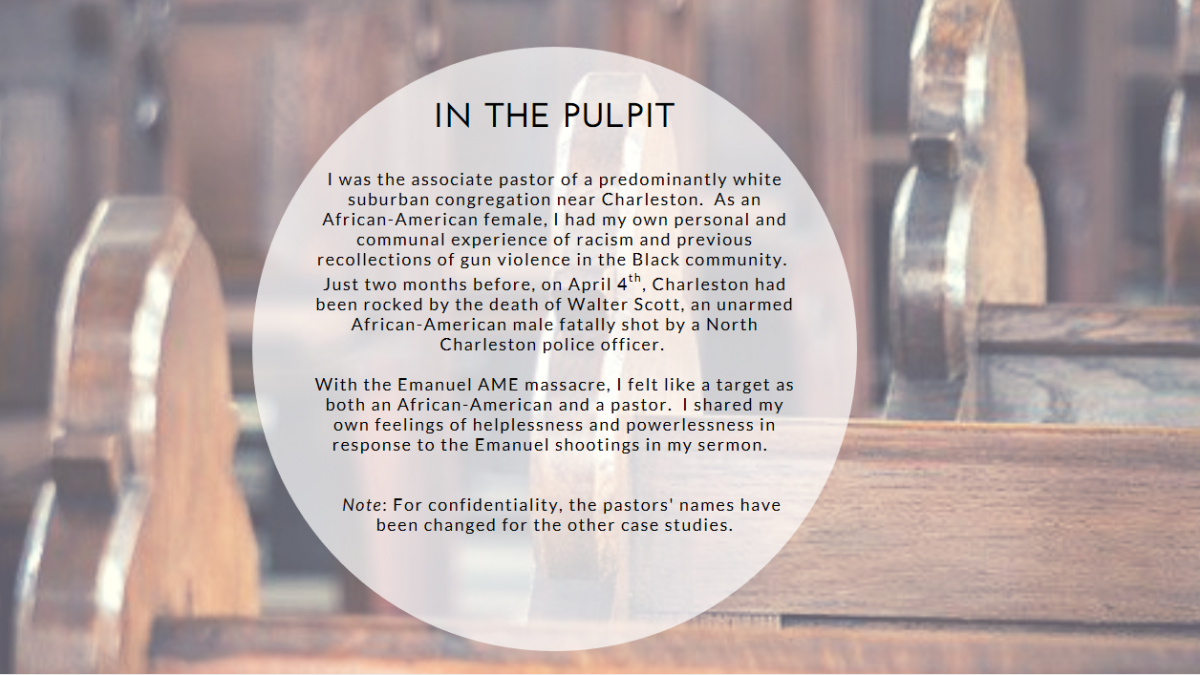

I argue that effective pastoral preaching in response to communal trauma requires the pastor’s personal connection in proclamation. This connection is a challenge when communal tragedies can often paralyze our thoughts and confound our emotions. The pastor can use reflexive practice to become self-aware of personal narratives, cultural worldviews, issues related to gender, race, sexual orientation, family history, spiritual injuries, theological assumptions, and more. That self-awareness enriches the preacher’s ability to articulate response to the tragedy.

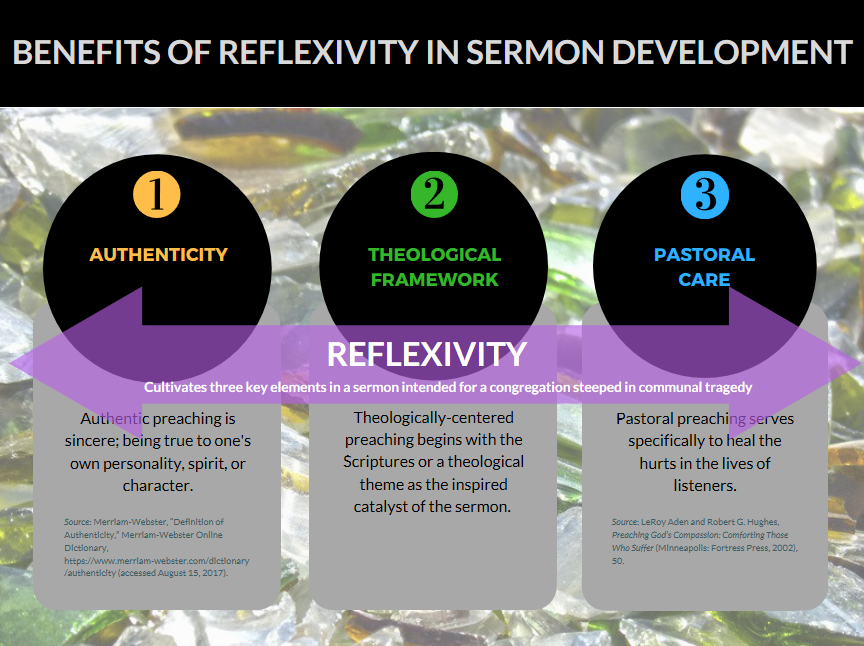

This self-awareness will help cultivate a sermon as pastoral response. Developing a sermon does not begin with the pastor but with God’s Word for her congregation. Nonetheless, integrating reflexive practice into the theological reflection of sermon development will help pastors to both remain focused on the Good News, and appropriately use their own personal connection with the tragedy to offer authentic, pastoral preaching. I argue that using reflexivity in sermon development helps pastors share themselves in preaching that is 1) authentic, 2) theologically-centered, 3) and pastoral to congregations suffering violent communal events like mass shootings or terrorism. I also examine four case studies that offer a window into the process of reflexive preaching of pastors in the Charleston district as they offered pastoral responses to congregations amid violent community trauma.

AUTHENTICITY IN PREACHING

Reflective practice is the means through which one appropriately shares the authentic self in preaching. Reflexivity is both a process to discover one’s authentic self and a pathway to present one’s true self in pastoral preaching. Reflexivity guides the pastor to bring her own narratives, spiritual injuries, and struggles to the forefront. While this concept has its roots in psychoanalysis and later theories of countertransference developed in the fields of psychotherapy and pastoral counseling, it is relevant in considering the authentic use of self in preaching.

The use of our authentic selves in preaching creates connection and trust with our congregations—opening preaching as a compelling means of pastoral care in congregations facing crisis and trauma. For many pastors, sharing themselves in a sermon—often through a personal story—is not an unusual practice. However, pastors often underutilize this powerful tool of sharing the “self” because they do not reflect deeply on how their life experiences impact the groundwork for their preaching. Instead, sharing one’s self is reduced to last-minute casual storytelling like “this week, you won’t believe what happened to me in the grocery store.” Or “My kid is so funny, let me tell you what he said to me in the car….”

These personal anecdotes often do nothing more than interject humor in the sermon’s introduction or serve as a superficial transition between key points in an otherwise impersonal sermon. Even more carefully crafted personal stories can do more harm than good without reflection on one’s own personal history, struggles, and motivations for sharing personal stories. For example, without careful reflection, our stories can unintentionally distort or distract from the sermon’s gospel message, overexpose close family and friends who are often the subjects of these stories, or alienate or distract our congregation with personal biases or hurts that should be addressed outside of the pulpit.

Without careful reflection, our stories can unintentionally distort or distract from the sermon’s gospel message, overexpose close family and friends who are often the subjects of these stories, or alienate or distract our congregation with personal biases or hurts that should be addressed outside of the pulpit.

However, with intentional personal reflection, the positive potential of using reflexivity in preaching can far outweigh the risks. Sharing ourselves in the pulpit is a tremendous opportunity to create a strong conduit for pastoral care through our preaching—especially in crisis. Seeing the pastor’s faith, doubt, joys, vulnerabilities, and sincere emotion in the preached word can bring renewed connection and even authority within the congregation.

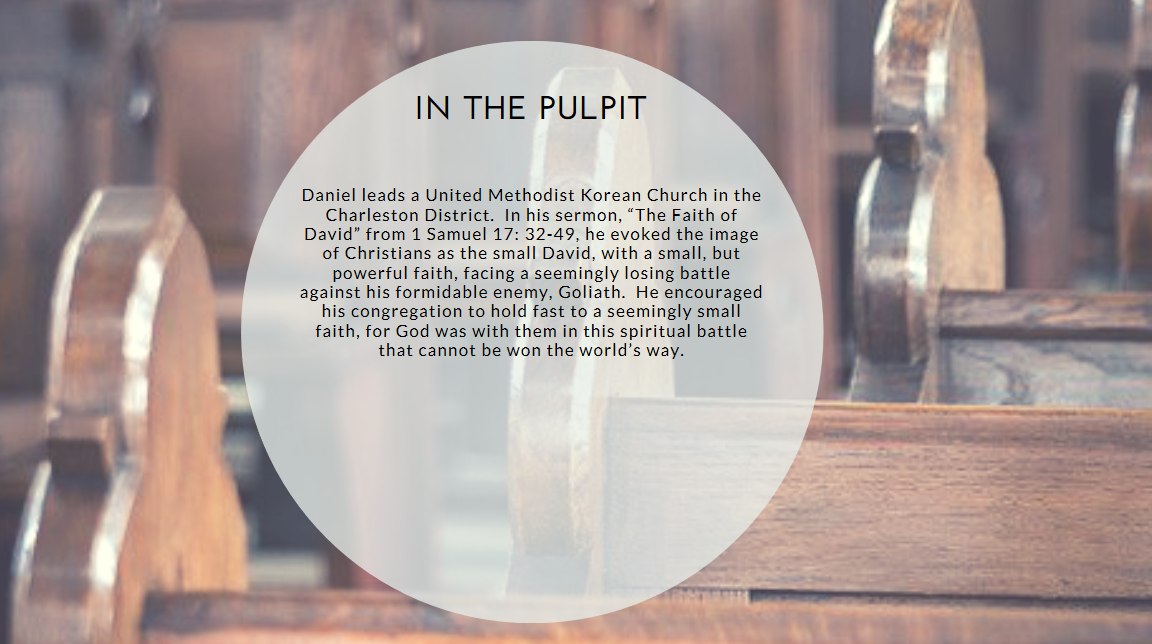

THEOLOGICAL FRAMING

For preaching, reflexive practice is only helpful if it is going to be a part of a larger theological reflection that gets the sermon developed and polished for Sabbath worship. As the pastor prepares to face a congregation reeling from tragedy, sermon writing is more than just a personal pursuit of self-awareness and meaning. Sermon development does not begin with the pastor—but with God’s Word for the congregation. Integrating reflexive practice into the theological reflection of sermon development will help the pastor to both keep sight of the Good News, and also appropriately use their own personal experience for authentic, pastoral preaching.

Sermon development does not begin with the pastor—but with God’s Word for the congregation. Integrating reflexive practice into the theological reflection of sermon development will help the pastor to both keep sight of the Good News, and also appropriately use their own personal experience for authentic, pastoral preaching.

Pastors may already have some theological reflection practices in mind as they sit down for sermon development. Some pastors may begin with the Lectionary readings for that Sunday. Others may not have a specific set of Scriptures in mind, and dutiful reflection will yield the appropriate Scripture at some point in the reflection process.

I recommend the following steps to guide one’s theological reflection for writing a sermon for communal trauma:

Step 1: Listening to the Divine

The process of listening to the divine may yield a biblical story or image, a sacramental theme, or contemporary theological image or metaphor. This step is about making an initial connection between the relationship of the image or text, the crisis, and the congregation. After receiving divine inspiration, these connections will be the groundwork for personal reflexivity.

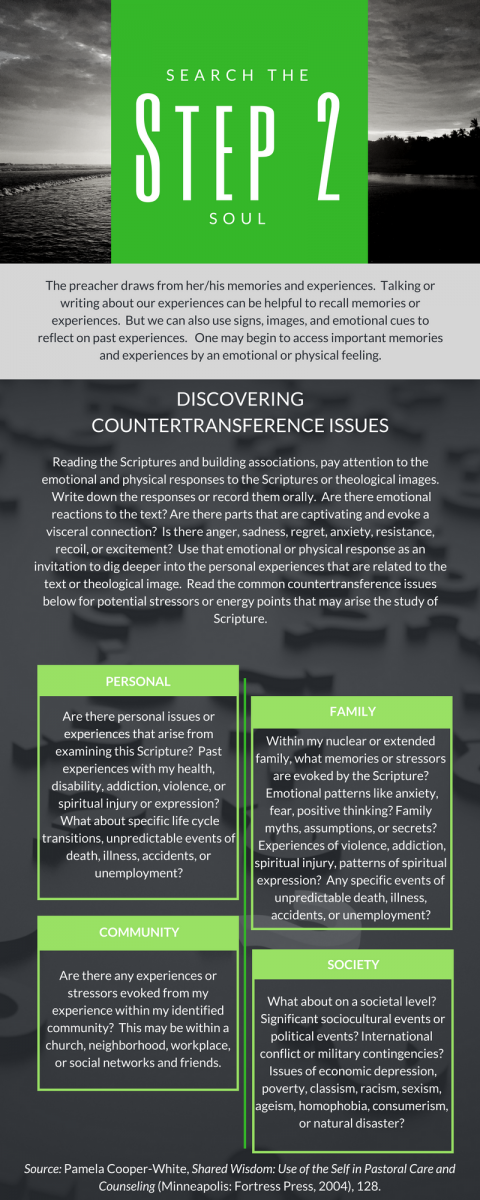

Step 2: Search the Soul (Discovering Countertransference Issues)

The goal of this step is to uncover and reflect on personal experiences. Talking or writing about our experiences can be helpful to recall memories or experiences. But we can also use signs, images, and emotional cues to reflect on past experiences. One may begin to access important memories and experiences just by the initial emotional or physical feeling during private reflection.

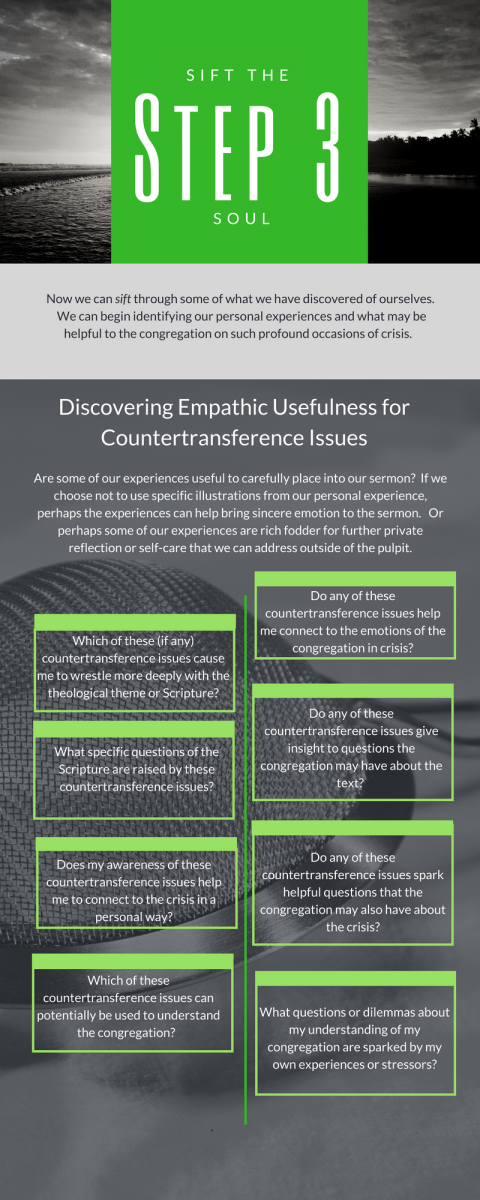

Step 3: Sift the Soul (Discovering Empathic Usefulness for Countertransference Issues)

Now we can sift through some of what we have discovered of ourselves. We can begin identifying our personal experiences and what may be helpful to the congregation on such profound occasions of crisis.

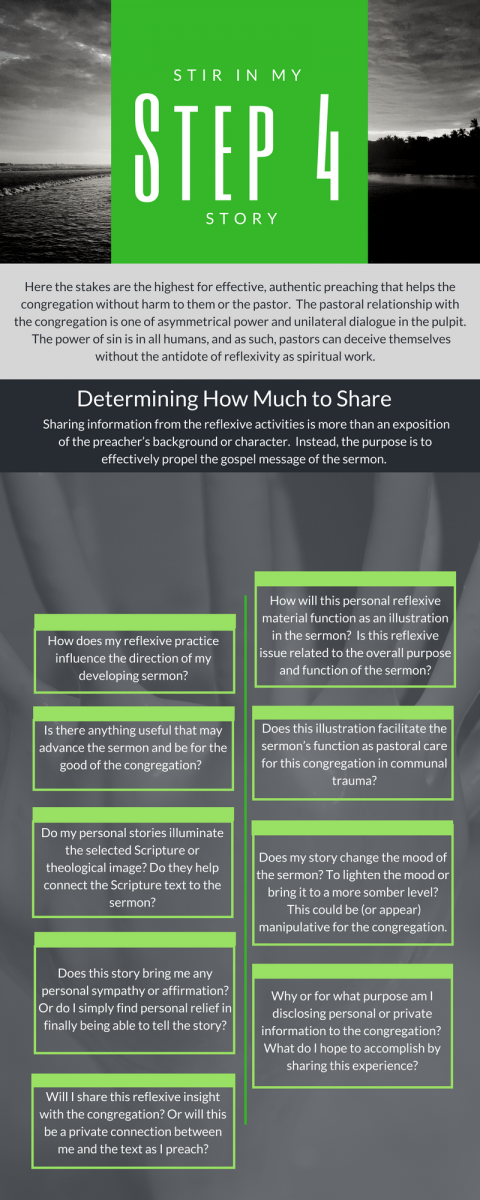

Step 4: Stir in My Story

Here the stakes are the highest for effective, authentic preaching that helps the congregation without harm to them or the pastor. The pastoral relationship is one of asymmetrical power and unilateral dialogue in the pulpit. Sharing information from the reflexive activities is more than an exposition of the preacher’s background or character. Instead, the purpose is to effectively propel the message of the sermon.

PASTORAL CARE

Reflexivity has tremendously informed pastoral counseling, and I argue that a similar practice of reflexivity can be helpful in the homiletic process as well. The situation of preaching is quite different than the intense, clearly defined relationship of psychodynamic therapy or pastoral counseling. The task of preaching shifts the understanding of reflexive practice from a therapeutic tool of individual pastoral care to a means of public pastoral care for the congregation. In preaching, the pastor’s focus is on God’s Word and its calling for God’s people—not just the context of the individual and his/her private perspective.

The task of preaching shifts the understanding of reflexive practice from a therapeutic tool of individual pastoral care to a means of public pastoral care for the congregation.

LeRoy Aden and Robert G. Hughes understand pastoral preaching to function specifically to heal the hurts in the lives of listeners.1 As a preacher begins to form the sermon, Aden and Hughes encourage pastoral sermons that address this kind of suffering to have two movements.2 The first movement addresses the problem of suffering. The preacher can choose to paraphrase or retell the biblical story in the sermon. The pastor can also choose a contemporary story to bring the implied suffering in the biblical text closer to contemporary reality. The pastor may at this point also choose to use a personal story.3 The second movement of the sermon is the response of faith. Here the pastor addresses what God, Christ, or the Holy Spirit is doing or saying in the text in response to the suffering being experienced.4 The pastor can articulate our human response to the gospel.

CONCLUSION

The Emanuel Nine shooting terrorized and shocked an American public that had already witnessed its share of violent mass shootings. Most recently, we witnessed the mass shooting of fourteen students and three faculty at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida on February 14, 2018. Like the Emanuel Nine massacre, we will never forget the murder of twenty-six worshippers in Sunday morning service at First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas on November 6, 2017. Both events challenge pastors with a tremendous preaching task. We know the sermon in response to communal trauma like domestic terrorism and mass shootings must be different—this is not going to be Sunday worship as usual.

Effective pastoral preaching in response to communal trauma requires the pastor’s renewed commitment to a personal connection in proclamation. As we saw in the case study excerpts above, preachers will engage in reflexive practices in ways consistent with their own identities and contexts. During sermon development and theological reflection, the pastors not only engage the Scripture—but must face themselves in reflexive practice. We cannot step around the violent evil that raises its head upon unsuspecting victims. Future crises in the form of terrorism or mass shootings will likely target our communities again.

Preaching to congregations in crisis is less about finding the right words to say, and more about bringing sincere emotion, wisdom, and experience to the proclamation task. In moments of communal trauma, the congregation not only wants God’s Word but reassurance from their pastor. A personal connection to the preacher is a connection to God’s embodied agency in this world. Through reflective practice, pastors can dig deep and discover healthy ways to use their own personal wisdom and experience to deliver the gospel message to the congregation.

A personal connection to the preacher is a connection to God’s embodied agency in this world. Through reflective practice, pastors can dig deep and discover healthy ways to use their own personal wisdom and experience to deliver the gospel message to the congregation.

What emerges is a sermon that is 1) authentic, 2) theologically-centered, 3) and a means of pastoral care to congregations suffering violent communal events like mass shootings or terrorism. Future research could qualify the effectiveness of reflective practice in sermon preparation using feedback after the sermons from pastors and congregations. Further research could also hone better reflective questions that cultivate pastoral preaching in crisis. We pray for an end to the nightmarish trend of mass shootings in our country. We pray that God might use our story to proclaim God’s victory over evil and the hope of Christ amid despair in a world that groans for Christ’s return.

1. LeRoy Aden and Robert G. Hughes, Preaching God’s Compassion: Comforting Those Who Suffer (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2002), 50.

2. Aden and Hughes, Preaching God’s Compassion, 52.

3. Aden and Hughes, Preaching God’s Compassion, 53.

4. Aden and Hughes, Preaching God’s Compassion, 55.