On October 5, 2017, Jeffrey Rosen, President and Chief Executive Officer of the National Constitution Center, presented a lecture entitled, “A Question of Citizenship: The Fourteenth Amendment Yesterday and Today,” at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis. Rosen explained that the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees “due process of law” and “equal protection of the laws” to all citizens, and, as a result, it has served as one of the pillars of civil rights law since its ratification.

I listened to Rosen’s hour-long presentation, then greeted him after he had concluded. I wanted to share with him some sobering statistics about Memphis – and the fact that more than 50 years after the Civil Rights Act had been passed, and more than 100 years after the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution had been ratified, African American persons in Memphis remained 2½ times more likely to live in poverty and were nearly twice as likely to be unemployed. Despite the population of Memphis being approximately 63% African American, public schools in Memphis were nearly 68%+ African American and 12%+ other children of color[1]; and, the greatest number of low-performing (“failing”) schools in the state of Tennessee were located in Memphis, and serving students of color in our city’s poorest neighborhoods.[2] Rosen asked my thoughts about why Memphis – and other communities – had ended up in these circumstances, and I replied that I believed that there had been an assumption that once our nation had taken legal measures to “fix” to our segregation “problem,” our work would be done. Rather, I continued, that was the point at which our work to come together as a nation should really have just begun. Otherwise, I pointed out to Rosen, the Fourteenth Amendment should have accomplished everything that we struggled for the next 100+ years to accomplish.

Rosen’s lecture helped to clarify for me that while our nation has relied upon the executive, legislative and judicial branches of our government to advance the goals of equality and justice, those goals remain largely unfulfilled in communities like Memphis. If government has done all that it can to legislate desired outcomes, where, then, might we look for the leadership that is needed today to bring our communities together in intentional dialogue to discuss our painful shared past and move us toward a reconciled future?

The Role of the Church in Racial Reconciliation Dialogue

(image origin unknown)

(image origin unknown)

In my paper, “A Model for Racial Dialogue: Matthew 15:21-28 – Jesus and the Canaanite Woman,” I suggest that the Christian Church can and should be the driving force toward racial reconciliation in the 21st century – in Memphis, Tennessee and in other communities in our nation. The reasons are two-fold, and both biblical. First, it is the Church that professes belief that humankind is made in the image and likeness of God, and that we are commanded by Jesus to love one another (John 13:34-35). Second, the Gospel accounts of Jesus healing physical afflictions also speak to the healing of “wounds of oppression and alienation, as well.”[3] These Christian messages which speak clearly to love, healing, and reconciliation are sorely needed in our nation today.

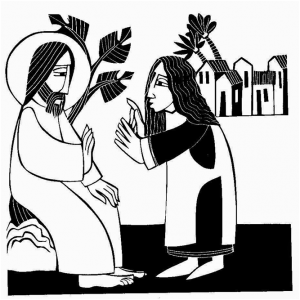

The paper explores the use of Matthew 15:21-28, a text which describes Jesus’ encounter with a Canaanite woman seeking healing for her daughter, as a means for opening conversation for racial reconciliation dialogue. The text of Matthew 15:21-28 holds a particular intrigue as a starting point for racial reconciliation dialogue, as readers are given a marvelous glimpse into the prejudices and biases of the first century world – and a very human yet divine Jesus. Readers are told in Matthew’s account of this story that the Canaanite woman approaches Jesus, asking that her daughter be healed; indeed, she is the first woman to speak in Matthew’s Gospel.[4] Jesus does not immediately respond to the woman, and when his disciples press him to send her away, Jesus tells them that he “was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matthew 15:24), suggesting that he will not heal anyone who is not Jewish. The woman begs again, and Jesus responds by telling her that “[i]t is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs” (Matthew 15:26). The term “dog” used by Jesus is understood as “a contemptuous term for the Gentiles”[5] and a term which is today interpreted as an ethnic slur.[6] The woman does not attempt to refute his characterization of her, but instead responds to him by saying, “even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ tables” (Matthew 15:27). Jesus tells her that, because of her faith, her prayer for her daughter’s healing will be answered (Matthew 15:28). The woman’s daughter has not accompanied her, and Jesus has healed her from a distance.

Scholar Musa Dube and others argue that Matthew’s account suggests the racial and class superiority of Jesus and the racial inferiority of others.[7] Indeed, if we subscribe to Dube’s notions regarding the status of a Canaanite woman at the time that Matthew’s Gospel is written, it becomes easier to understand both Jesus’ reaction to the woman and the woman’s reaction to Jesus’ comments: He may well be accustomed to hearing such demeaning statements made about Gentiles and simply repeats what is familiar to him. She may well be accustomed to hearing such comments and slurs from Jewish people, and she makes no attempt to refute Jesus’ assertion. In her desperation to seek help from the one person who may be able to heal her daughter, she “humbly bear[s] the mockery of [Jesus’] attack.”[8] She is willing to accept the crumbs, believing them to be more than enough to satisfy her needs, but she is persistent, in asking for what she knows that Jesus can provide.

Scholar Elizabeth Vasko, who authored a study of the Matthean text entitled, Beyond Apathy: A Theology for Bystanders, suggests that the first step toward a reading of this text for liberation, social change and healing is to recognize privilege. Privilege is not found only in race, but also in gender, ethnicity, age, ability, education, sexuality, class, language and culture, to name but a few of its sources. Vasko comments that,

Jesus would not have been able to escape the reality of empire, social class, gender, or ethnicity. In his humanity, he would have been socialized into an environment that privileged maleness over femaleness, Jewishness over non-Jewishness, and held marked assumptions about ethnicity and race.[9]

The text, in Vasko’s words, “throws a mirror up” to privilege and bias by bringing the privileged party face-to-face with his transgressions and asking how persons of privilege may be complicit in committing acts of injustice against those who are not privileged.[10] At the same time, the encounter shows an oppressed party who is able to stand up for herself. The Canaanite woman is not portrayed as a victim or a passive person, but rather as a persistent presence who, although initially ignored, recognizes the possibility for healing even where there has been an initial offense, stands her ground and demands to be heard, and ultimately receives the healing for which she has come. Just as the woman steps out of her own boundaries as a woman of the ancient world and as a Gentile in a Jewish community, challenging Jesus to minister beyond the boundaries to which he is accustomed, so she sets the example for the persistent oppressed party to challenge those in positions of authority and privilege to “minister” beyond expected boundaries, so that all become boundary breakers.[11] And, the Canaanite woman calls her oppressor to account for the ways in which he has become caught up in prejudice and encouraged injustice.[12]

Vasko finds that the face-to-face encounter is an indispensable step toward reconciliation and healing. “This flesh-and-blood encounter, while uncomfortable and messy, is where healing begins to take shape,” she states. Through the encounter we are able to listen to others and view them as worthy of respect rather than helpless beings in need of a handout.[13] For the oppressed person, Vasko finds that there must be a refusal to take “no” for an answer from the privileged parties. There is, she notes, the grace of privileged ambush, in which those who are oppressed call the Church to account “for the ways in which [its] mission and vision have become caught up in ethnic prejudice and religious exclusivism.”[14]

It is from Vasko’s notion that the face-to-face encounter is essential that I developed the idea of a workshop that would pair Christians from black and white churches for a morning or full day of intentional dialogue, using the Matthew 15:21-28 text as a basis for that dialogue. The workshop is presented as the basis for opening dialogue between African American and white Christians, to illustrate a way in which those in positions of privilege and authority and those who have been oppressed may come to the table together, and remain in dialogue without leaving in frustration, with healing for a community being the result. The workshop is presented as a tool for reconciliation within the Christian community itself that can be taken beyond the doors of the Church and into the secular community – to help us all better understand how, working together, we can bring about much-needed healing in our nation.

The flow of the workshop was really shaped by Vasko’s book and questions. Workshop participants begin to process new understanding in a face-to-face encounter in which they are able to really listen to and hear the stories and thoughts of others who come from dissimilar backgrounds. Ample time is allowed for participants to interact in small groups, and for persons to share their experiences.

A key part of the workshop is a presentation entitled, “The History of Us – Black and White Together in the United States.”

This narrated presentation includes photographs – some very graphic – beginning with the first slaves being brought to Jamestown in 1619, through the present-day. Photographs and narrative include a brief glimpse at the economic benefits of slavery, the Civil War years, gains made during Reconstruction (following the passage of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution), Jim Crow laws, lynchings, and the 1950s-1960s Civil Rights era. Ample time is given for participants to respond to the images that they see.

The afternoon of the full-day session is spent in deep engagement with the text of Matthew 15:21-28. The text is contrasted with that of Mark 7:25-30, and also with Matthew 8:5-13. Participants are encouraged, as they consider these texts, to ask themselves among other questions (i) what they notice about Jesus’ conversation with the woman, (ii) what they observe about the disciples, (iii) what is different about Matthew’s and Mark’s accounts of Jesus’ encounter with the woman, (iv) what is different about Jesus’ encounter with the centurion, (v) and, critically, in a modern contextualization, who might represent Jesus (one with resources available for “healing” and restoration, but displaying some biases) and the Canaanite woman (one in need of “healing,” but one who more likely than not would be looked down upon) in our own society. A litany of prayers for forgiveness, healing and reconciliation has been incorporated in the workshop, as a way to close the time together with prayers for forgiveness, healing, reconciliation, continued dialogue, and commitment to work together to bring about justice for all of God’s people.[15]

It can become easy for those who occupy positions of privilege to ignore those who occupy a “lower” status and assume that there is nothing to learn and nothing to be gained from dialogue. It can be equally easy for those who have been oppressed and looked down upon to believe that there is nothing – not even crumbs – to gain from dialogue. What proves more difficult is for both sides to be able to sit down together, putting aside the barriers to dialogue to risk being willing to learn from one another. In that coming together, there is healing for everyone. In the Matthew text, the Canaanite woman’s daughter is not the only one who experiences healing. The Canaanite woman herself experiences the healing – in having her own faith strengthened[16] and in the assurance that God’s action did not exclude her. The disciples experience healing, too, in a not-so-subtle challenge to any presumptions that they may have held about Gentiles being within the ambit of God’s saving embrace[17]. The goal is that, through the workshop, participants are able to envision opportunities for healing and reasons for staying at the table together to bring about that healing.

Taking it to the streets…of Memphis

On April 4, 2018, the date which marked the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel (now the site of the National Civil Rights Museum), Memphis made great strides in community truth-telling, as the National Parks Service unveiled a new marker, designating the site of a slave auction mart owned by Nathan Bedford Forrest. On the heels of the controversial removal of a statue of Forrest from a public park last fall, Rhodes College history professor Tim Huebner’s students researched the location of Forrest’s original slave auction house – and learned that the market sat just behind Calvary Episcopal Church, in downtown Memphis, on land that the church had acquired for a parking lot. I was asked, after Dr. Huebner had participated in one of my workshops, to help design the liturgy for a Service of Remembrance and Reconciliation that would precede the unveiling of the marker. That service was attended by more than 600 persons, and worshipers at Calvary heard reflections from me and from the rector of Calvary Church…

…before hearing the reading of names that have been identified to-date of slaves sold at the mart (the youngest identified as having been only three months old).

(photo from Calvary Episcopal Church, Memphis, TN)

After the reading of the names, we prayed together a litany of prayers for forgiveness, healing and reconciliation – adapted in large part from the prayers that I developed from the workshop. Persons not of African descent prayed for forgiveness for “the lingering effects of our failure to love our neighbors as ourselves [that] have allowed a plague of poverty and disenfranchisement to engulf our sisters and brothers of color in forgotten communities in our city. Persons of African descent prayed for forgiveness “for the times that in our weariness, frustration and impatience, we have failed to see all of your children as being entitled to your mercy and love.” Together, we prayed that God might “make us conscious of the ways in which our blindness prevents us from seeing systems of oppression that continue to harm any of your people, and help us stand together to eradicate the lingering effects of racism that cripple our entire community.”

At the close of the service, we processed outside to unveil the marker, as hundreds of Memphians – white, African American, Christian and Jewish – gathered to bear witness to a painful truth but in the process open a way for healing, while honoring the life and legacy of one who during his own ministry bore witness to truth and stood in opposition to injustice and oppression.

(photo from https://www.memphisdailynews.com/news/2018/apr/5/last-word-mlk50s-big-day-hotel-changes-and-murica-on-capitol-hill//print)

The response to the service and unveiling has already given many of us great hope; already, conversations about education, jobs and lifting our most vulnerable neighborhoods are taking a fresh direction. Might this time of community truth-telling and prayers for forgiveness and reconciliation truly give our city a fresh start?

[1] http://publicschoolsk12.com/all-schools/tn/shelby-county/

[2] Laura Faith Kebede and Grace Tatter, “Here’s where Tennessee’s lowest-performing schools stand a year before the state’s next priority list,” Chalkbeat.org, April 20, 2016, accessed August 16, 2017, https://www.chalkbeat.org/posts/tn/2016/04/20/heres-where-tennessees-lowest-performing-schools-stand-a-year-before-the-states-next-priority-list/.

[3] Walter T. Wilson, Healing in the Gospel of Matthew (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2014), 21.

[4] Kenneth E. Bailey, Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2008), 222.

[5] Donald Senior, Matthew (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1998), 182. [6] See, Amy-Jill Levine, The Social and Ethnic Dimensions of Matthean Social History (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1988), 150. It does not appear that Jesus utters another phrase in either of the Gospels – other than the reference to the dog in Matthew 15:21-28 and Mark 7:24-30 – which could be interpreted as an ethnic slur. [7] Musa W. Dube, Postcolonial Feminist Interpretation of the Bible (St. Louis: Chalice Press, 2000), 147.[8] J. Martin C. Scott, “Matthew 15:21-28: A Test-Case for Jesus’ Manners,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 63, no. 1 (Summer 1996): 42.

[9] Elizabeth T. Vasko, Beyond Apathy: A Theology for Bystanders (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015), 177.

[10] Vasko, 155.

[11] See, Daniel S. Schipani, “Transforming Encounter in the Borderlands,” in Redemptive Transformation in Practical Theology: Essays in Honor of James E. Loder, Jr., ed. Dana R. Wright and John D. Kuentzel (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2004), 127.

[12] Vasko, 215.

[13] Vasko, 184.

[14] Vasko, 215.

[15] The litany of prayers from the workshop (i) was adapted by the Memphis Christian Pastors Network for use at a community worship service commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the 1968 Sanitation Workers Strike in Memphis, which drew Rev. Dr. King to the community before his assassination, and (ii) was adapted for use at a public service on April 4, 2018, at which a historic marker denoting the site of the slave auction house owned by Nathan Bedford Forrest, and adjacent to Calvary Episcopal Church, in downtown Memphis, was unveiled.

[16] Kenneth E. Bailey, Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2008), 222. [17] Bailey, 222.