Introduction

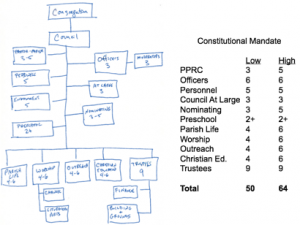

The church is not a machine, but pastors are often expected to function as if they are operating one. That is the basic problem identified by my Doctor of Ministry project. The systems that govern mainline protestant churches resemble post-industrial modern machines, like airplanes, consisting of carefully engineered component parts. They are led by corporate bodies known as general boards, judicatories, and instrumentalities. Values of efficiency, order, and control often seem prized as much as the Gospel these vessels were built to convey. But if the church ever was a well-oiled machine, today it is an aging and clunky one. The basic structures of the church for membership and financial support regularly malfunction. So my intention is to invite pastors to see their work in a different way. If we take seriously the image of the church as the Body of Christ, the work of pastoral leadership is not the work of technicians but of healers. We deal with a mystical body, not a modern machine.

This hierarchical diagram shows how a church with little more than 60 regular worshippers needed to enlist about that many in positions of governance and leadership. The machine doesn’t work like it used to.

Organizational Leadership Theory

Conceptually, my project is rooted in literature on organizational leadership and theology. Margaret Wheatley’s Leadership and the New Science argues that scientific discoveries of the Twentieth Century broke with earlier Newtonian sciences characterized by a more mechanistic worldview. Organizations are like other living systems observed in botany, medicine, and chaos theory. “There is an inherent orderliness to the universe,” Wheatley argues, urging a more trusting and curious approach to management than the authoritative and controlling approaches typical of Twentieth Century corporate life.[1] Wheatly says that a leader is not a hero who holds everything together but a “host” who attends to the relationships and interdependencies at the heart of a community’s life together.

“If you want a system to heal, connect it to more of itself.”[2]

Practical Theology

If the church is a living body and not a machine, an important function of pastoral leadership is to help the body adopt life sustaining practices that are aligned with the gospel. Mary McClintock Fulkerson describes how a congregation might build a habitus, or a competency that lives in the muscle memory of the collective body, to guide the church in a manner consistent with its purpose and values.[3] Her study of Good Samaritan Church shows how a Methodist congregation applied its commitment to hospitality “improvisationally” in the midst of changing neighborhood and economic conditions.[4] The key for Fulkerson is to observe whether the church can apply the same principle in response to new or differing circumstances. In other words, she demonstrates that the Body of Christ can learn. Drawing on her work, my project shows how the use of participatory leadership practices helped my congregation build a new habitus. In our case, the intention was to increase our ability to connect humanely with one another, tolerate a measure of risk for the sake of our mission, and experiment with new program ideas. Could our living body also learn?

Practices of Participatory Leadership

Tenneson Woolf introduced me to a body of work known as the Art of Hosting, which he defines as

a global community of practitioners using integrated participative change processes, methods, maps, and planning tools to engage groups and teams in meaningful conversation, deliberate collaboration, and group-supported-action for the common good.[5]

We used three specific planning tools to engage my congregation over a period of nine months to devise five “strategic experiments.” Each of these processes is intended to place the pastor in a convening position—calling the group together to explore an important question—rather than in an expert position of providing answers to the questions.

- The World Café: An exercise to mobilize a larger group into more intimate small-group conversations and harvest the energy and ideas that emerge.[6]

- The Circle Way: A large- or small-group practice of speaking and listening in a circle with sustained attention to the well-being of the whole group.[7]

- Open Space Technology: A minimal structure for planning that summons the passions and interests of motivated members of the group.[8]

The intent was to reduce the church’s dependence on an expert pastor and to increase its ability to work with the community’s gifts to offer missional programs in the life of the church. Our participatory approach to ministry planning yielded “self-organizing, passion-driven ministry teams” in these areas.

- Christian Education: This has involved the development of a Godly Play classroom that now enrolls more than thirty students. We also engaged a local rabbi and faculty of the nearby college to expand our offerings to young adults and elders.

- Caregiving: We immediately identified a group of laypeople, mostly elders, who wanted to learn more about how to provide care to people who are ill, aged, or homebound. As pastor, I began offering training sessions similar to Stephen Ministry programs. This soon evolved into the Care Connection Team that met with me monthly to review caregiving needs in our congregation.

- Small Groups: In the beginning of this experiment, several individuals with gifts for hospitality simply invited the church to participate in fun events. One family that had an orchard of apple trees invited the church to make apple cider. Another group initiated a Christmas caroling event. In time, this initiative evolved into a vision for a formal small group program for church members.

- Social Justice: This is a generative theme showing up throughout our congregation’s history. Sensing energy behind environmental justice, the Care for Creation Team was born to educate the community about climate change. This team leveraged our connection with the local college to host community workshops and offers an annual Earth day worship service.

- Ecumenical Projects: This team was unsuccessful in identifying concrete ministries to undertake. Nevertheless, the spirit of their initiative has endured through other teams that have focused on building partnerships with sister churches in the community.

Measuring Impact

Could the church learn to take seriously its existing gifts and assets for ministry? Could it learn to look less to the expertise of the pastor and more to the heart of the congregation? I was hoping to see evidence that a new competency had developed, a new habitus in the muscle memory of the body. After leaving ministry in the setting that I had served for four years where we had practiced these models of participatory leadership, I kept watching at a distance to see if the congregation could continue its spirit of experimentation.

Two examples emerged in the church’s newsletters and Facebook feed showing an ongoing commitment to experimentation. The first was an improvisation on a children’s ministry program we had developed while I was pastor. They brought Godly Play materials into the sanctuary to create a “PrayGround” at the heart of worship so that children would not have to leave the sanctuary during the service. Said the church’s moderator in an email explaining the experiment:

A new experiment is to have an area at the front of the sanctuary for the children to play quietly during the service. Two pews were removed to open up this space. It has been available for two Sundays and is working well. The children have been much more quiet when there than when squirming in the pews.

It is clear that the church was applying its resources for children’s ministry in a new way, improvising on a former theme–the moderator’s judgmental remark about squirming children aside!

A second experiment emerged from our focus on ecumenical projects. The congregation sponsored a “Jingle Bell Holiday” in the season of Advent in partnership with other community associations. The church office explained in its newsletter:

This was a collaborative effort with the Children’s Choir and the Community Preschool, and another of our “holy experiments.” Feedback has been wonderfully positive and we have already brainstormed some ideas to make this an even more impactful event next year.

Conclusion

The chief conclusion of my project is that practices of participatory leadership in a congregational setting can help the church to build a new habitus by tightening the social fabric of the community. In other words, by taking seriously the church as an image of the Risen Christ, the church can learn new competencies. The congregation that I served is able to improvise on its mission in response to changing circumstances. That is evidence that the leadership practices we employed have had a sustained influence on the character of the community. Old industrial machines are not capable of learning. But a living, breathing, dynamic body? We can teach it good life-sustaining habits in keeping with our Gospel mission.

[1] Margaret J. Wheatley, Leadership and the New Science: Discovering Order in a Chaotic World, 3rd edition (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2006), 4.

[2] “The Servant Leader: From Hero to Host. An Interview with Margaret Wheatley by Larry C. Spears,” November 15, 2002, https://www.margaretwheatley.com/articles/herotohost.html.

[3] Mary McClintock Fulkerson, Places of Redemption: Theology for a Worldly Church, 1st ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 43.

[4] Fulkerson, 48.

[5] Tenneson Woolf, “What Is the Art of Hosting?,” Tenneson Woolf Consulting, accessed February 16, 2019, http://tennesonwoolf.com/what-is-the-art-of-hosting/.

[6] Juanita Brown and David Isaacs, The World Café: Shaping Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter (Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2005).

[7] Christina Baldwin and Ann Linnea, The Circle Way: A Leader in Every Chair (Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2010).

[8] Harrison Owen, Open Space Technology: A User’s Guide (Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2008).