a pastor’s vision for transforming a dying church

into a resurrected, resilient community

When I first came to Old West Church from Georgia, I was told it was a “problem church,” a “pastor killer.” I was told I had been brought to this “difficult” charge in New England to either close and restart the congregation or to revitalize it. Most people, including the conference, thought OWC was dying.

This is not the story of a pastor fixing a church (because, spoiler alert: turns out, that’s not possible. And simply inviting a young person1 to be minister is not enough to turn around a dying congregation).

This is a small part of my journey in learning the history of this church, its context, seeing the church redefine itself around core values, and setting out a potential vision supporting these values for what the church could look like in the future.

This is a small imagination of what the future of the church, our structures, might look like. I hope you will join me on the journey, and in the vision of what the church may look like in the future.

Old West Church is dying.

While not hemorrhaging losses, Old West Church‘s (OWC) current congregation (30 members, 25 avg. worship attendance in 2018) cannot continue to maintain its premises, especially with its current restoration and renovation costs coming in at a cool $3,878,423. With less than a dozen giving units and an endowment under $120,000, OWC drops a little further into the red with each passing year.

Considering Protestantism’s decline across the American landscape,2 dying churches are not remarkable. Given that “6,000 to 10,000 churches”3 close each year due to building costs, OWC’s financial situation is not all that surprising. It is surprising how long OWC has existed without institutional support from the conference or any significant injection of finances.

So why not let OWC die?

Even if all the renovation and restoration money is raised, more maintenance will be needed in the future. Be it in ten or twenty years, OWC will once again have to raise substantial sums to maintain the building’s upkeep.

With the odds stacked against survival, why go through the herculean effort of raising such an amount for a small congregation in a financially-tenuous, high-maintenance space?

Thus, I ask again, why not let OWC die?

We could use the sale of this National Historic Landmark to fund new initiatives in and around the New England United Methodist Conference (NEC).

Plus, selling and merging is the norm. Dying congregations continue to deplete their resources until they are unable to finance any continuation. Then they sell their building and either fade away or merge into another existing congregation. For many dying churches, the income from their building sale goes back to the conference. Though painful, this direction is the simplest and the one most taken by dying churches.

But churches are still dying.

While sale of the building might negate OWC’s own financial issues, it doesn’t address the systemic issues of church decline and the balancing act many congregations are facing attempting to manage building and staffing costs against dwindling finances.

Maybe there’s a better way to let OWC die and rise to a new life, a new vision of how we shape and fund our community.

With a bit of boldness and a lot of hope, I suggest a second way, an option outside of closing, building sale, and potential merger. This way is the way of resurrection and resiliency, grounded in the core values of OWC. Though the history, core values, and plan I present are specific to OWC, there are takeaways that could be used for other congregations, other ways that churches can reimagine who they are in a changing reality.

But first, a lesson in history…

In 1961, Jane Jacobs wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities, a groundbreaking critique of urban renewal that was the first substantive pushback against the dominant approach to city planning throughout most of the twentieth century.

Urban renewal was the name of redevelopment programs that cities employed to address “blighted areas,” namely what the city officials considered unsightly or unseemly, for example, tenement housing and areas with lower income populations. The redevelopment’s goal was to create higher income spaces for higher income persons, often taken by eminent domain.

However, urban renewal was often just racism and classism thinly disguised as redevelopment in urban centers. Not only was it controversial for its forcible removal of the low-income families and businesses, but also by the resale of the land to private developers.

One of the places Jacobs critiques for their urban renewal tactics?

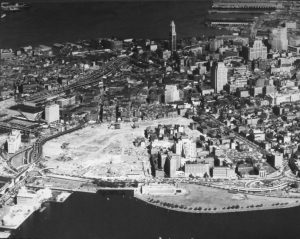

Boston. Specifically, Boston’s West End.

Once an early haven for African-Americans4 and home to Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish immigrants, the West End was left without an identity as all inhabitants were forced out. In this “deslumming” process, the entire neighborhood was razed, destroying over two centuries of identity, history, and character.

Of the forty-six acres of closely packed buildings in Boston’s West End, only three structures survived Boston’s urban renewal: a tenement house5, the Otis House, and OWC. As a result, “Boston’s downtown has suffered miserably”6 with little to no mixed-use space.

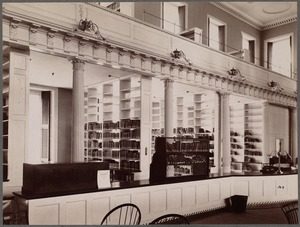

The NEC of the United Methodist Church (UMC) capitalized on the social upheaval of the 1950s (specifically, the removing of thousands of families in order to “renew” Boston) by purchasing the OWC building, then functioning as the West End Library, from the city of Boston in 1961. Their intention: create a cathedral of Boston Methodism.7

For a few years, the conference poured in resources. But the vision of the New England Conference of this being a cathedral to New England Methodism has never been realized. The church never grew to more than fifty persons.

Seen as a failure, the NEC withdrew financial support, transitioning OWC from three full-time appointments funded by the NEC to one full-time appointment, supported solely by OWC, effective immediately. This left a small congregation responsible for maintaining this historic building, including the responsibility of the lien imposed by Historic New England ensuring the historic edifice would continue to be properly maintained by the purchaser. Granted, the purchaser was NEC, but OWC is financially responsible. The decisions of the past are a burden, but they are not a coffin for ministry in the West End.

Core Values and Culture Shift to Enliven Our Imagination

Early on, OWC recognized its way of life (being the number of people in the pews [now chairs], income versus expenses, etc.) was unsustainable and expressed the need for change. A major aspect of recognizing and accepting the need for change is the courage to simply say, “yes.”

Within six weeks of my arrival at OWC on July 1, 2014, I said the church should get rid of its pews. The sanctuary was the only large meeting space and was completely inflexible due to the 14′ pews bolted into the floor.

Fare Thee Well, Pews!

Sweet, Sweet Flexibility of Infinite Possibility.

Pew removal was key to realizing this vision. The removal of the pews has already allowed OWC to host events and groups that it would have never been able to accommodate before.

One such group is Oasis Monday Night Dinner. This weekly dinner serves over a hundred guests a delicious, healthy meal, as well as offering other opportunities for community building such as book clubs. Originally started at OWC a few decades ago, it has been located at a few other churches over the years, but I am thrilled that it has come home to OWC.

Other opportunities that the pew removal produced includes hosting the poster making and community organizing for the Women’s March, Rally for Trans Rights, Boston Pride, and many climate justice and climate change gatherings, education, and policy events. We’ve also hosted many overnight youth groups from around the country coming to Boston to do volunteer and service work in the community.

As another early response to this realization, OWC participated in the Growing with Hope (GWH) program from fall 2015 to spring 2016. This “year-long process intends to support, challenge, and equip teams from each church to move to a deeper level of living out their mission.”8 Out of GWH, OWC distilled four core values: inclusive community, racial equity and social justice, transformational worship, and prophetic service.

Since 2016, these values have been the center of OWC’s mission and organization. All that nurturing and imagining about who OWC is and can be centers around these values. They function as a litmus test for the community. All decision making, all budget proposals, rental agreements, events, liturgy, and use of space must align with at least one of the core values. If it does not, or it negates one of them, it is not considered by the leadership team.

Small Changes are NOT Enough

The revisioning of the church cannot be limited to what already is or what has been. Gil Rendle9 clarifies the important difference between altering existing structures and true innovation: “Institutions think that they have to do what they’re doing, but better. But this is not about improving, it’s about creating.”10

Even with the guidance of the core values, whether OWC is willing to undergo resurrection or will simply be satisfied with making minor modifications to defer death a little longer, is up for debate. Small changes will not result in an institutional resurrection. They do not provide a sustainable, resilient model. A dying community can become resilient, now and for the future, only after true innovation—and true innovation looks a lot like death! But the good news is, after death, there is resurrection.

Innovation is necessary to create resurrected and resilient systems. Innovation is crucial for the future of the church.

If a church does not adapt to changing needs and wants of its community, it will become irrelevant, and thus, untenable. Churches must be savvy in how they approach and reimagine how they will look and structure themselves in the future.

Rethinking use of space and reimaging how communities gather come from the same need, but perhaps, more importantly, the same want. Rethinking space includes, but is not limited to, reconfiguring space, broadening the limitations about who can use the space, when can it be used, and perhaps most difficult, how it can be used.

On Being host Krista Tippett offers a perhaps unintentionally theological charge for the church: not to foster renewal, but resiliency. Tippett points to the importance of resilience entering not just our lexicon, but our imagination: “from urban planning to mental health… resilience is a successor to mere progress, a companion to sustainability.”11 Like Jacobs, Tippett insists on resilience over renewal. Renewal is progress for the sake of process. Resilience, on the other hand, is grounded in the past and responsive to the future. Built into resilience is the shift from “wish based optimism to reality-based hope.”12 Our call is to nurture not only resilient people, but resilient communities, cities, and institutions.

Envisioning Resurrection

I envision a more hopeful, more sustainable way for OWC. The way of resurrection.

Jesus’ core beliefs and value structures did not change, post-resurrection. However, Jesus rising again to new life was different enough that people were not able to recognize him. Yes, the body was still there but it was a new thing. Resurrection is not the same thing. It is doing a new thing.

This is the culmination of accepting, embracing, and celebrating the death of OWC as we know it, and rising to a new imagination of how OWC can not only exist but thrive, now and in the future. With this model, I imagine a new possibility for OWC grounded in resurrection and resiliency, rooted in the core values of OWC.

Reimaging, revisioning, and realizing a new identity for OWC in this new way does not mean doing away the core values, but rather strengthening the purpose and increasing the impact around the core values. And this reimaging of a new identity grounded in a resurrection reality will result in new growth. It means being truer to ourselves, as OWC. It means that OWC will begin to look a little more like the kindom13 of God, dying to its old self and rising again to new life.

The result,

a way of resurrection:

resilien·city.

Introducing a Resilient, Resurrection Reality

Resilien·city is a multi-use space, home to the OWC worshipping community, a coffee shop, co-working space, social enterprises, and affordable housing micro-units. This vision incorporates the need for a totally renovated, fully restored 19th-century building while comfortably containing all of these unique but interrelated enterprises, each uplifting one another and the further OWC’s core values.

The sanctuary space will be home to coffee shop, social enterprises, and community tables, echoing the tables from the library, where people can come, gather, and work together. Designated co-working space, open to both individuals and groups, will be in the balcony on either side of the organ loft. Finally, the basement will be retrofitted for 4 – 6 micro-units (two family units and four individual units), capable of housing up to 12 persons, new resilien·city residents. These units will have a separate entrance allowing resilien·city residents to have privacy and independence.

Non-residents will have access to some of the basement, including eight fully ADA-compliant, inclusive, individual bathrooms, two shower stalls, and a washer and dryer unit. Regular access to showers, public restrooms, and clean laundry are major issues for housing insecure persons. Providing these essentials is just one way OWC can offer dignity and justice to all our community. Because, like the kindom of God, the city and the church in the city, “must include elements of reality, community, and diversity”14 in order to be livable, vital, and life-giving, for all persons.

The interior of OWC is not all that changes. Like I said earlier, everything, except our values, is up for grabs. OWC has been imagining its yard into a place where the community can gather, spend time, reflect, and simply be. Part of this transformation is the yard from simply a place of grass into a food forest. A food forest is not organized in rows like a traditional garden, but mimics a woodland forest, with different layers and types of plants intertwined, supporting, and benefiting from one another.

Currently, OWC is in the process of remediating its soil, damaged from centuries of urban pollution, so we are utilizing hugul mounds and keyhole garden beds to grow the majority of the food until the soil is healthy enough to plant directly into. As part of our little ecosystem, we have included a beehive, compost areas, and a drip irrigation system with the intention of installing an underground water capture and storage system to supplement the watering needs of the space.

In addition to the reimagining of what the interior and the yard could look like, we have also reimagined what our parking could look like. When the City of Boston told OWC we could no longer use the corner parking spot, we decided rather than let it just lie vacant and unused, we would reclaim it. With the amazing work of New Jersey artist, Lawrence Ciarallo, the boundaries of the former parking spot was transformed into a mural depicting four persons, diverse in age, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality, each with Boston connections who have served as influences and inspirations for justice and equity. The persons represented in this incredible piece of public art are Mary Oliver, Melnea Cass, W.E.B. DuBois, and John F. Kennedy. Behind their faces are a kaleidoscope of color and abstract colors with some of OWC’s values and beliefs peppered throughout.15

While resilien·city is a true reimagining of OWC’s use and design of space, at the center of this new imagining is OWC’s heart for fulfilling its core values to serve all of our surrounding community. We must be intentional about how we engage with all persons – those who simply walk past our fence, those who spend time in the food forest, and those who come through our front doors. This vision addresses both the space and the community in it, creating new opportunities to gather, organize, and interact with others, forging new partnerships and new relationships.

Getting it Done

So much has gone into making all of this possible, but I would say relationships are at the heart of it.

OWC had to develop roots, relationships, in the community before it could experience discernable, visible growth.

Some of this is attributed to showing up, saying, “yes,” and putting oneself and one’s space out there, available for unlikely events and partnerships. Much of my first two years at OWC was simply showing up and saying, “yes,” to everything. I know, boundaries. But hear me out. I said, “yes,” to invitations to events. I showed up at other groups’ events. I said, “yes,” to space requests as long as they were aligned with the core values. Our sanctuary has functioned as orchestra concert hall, opera performance practice space, sleeping accommodations to groups of up to 75+, protest staging ground, food prep space. We have said, “yes,” to dance classes, baby clothing swaps, international organ concert series, kundalini yoga classes, early music concert series, meditation workshops, high school eco-activist trainings, and rap symposiums.

In saying, “yes,” and showing up, OWC is slowly becoming a place that people associate as being open to experimentation, at the intersection of cutting edge ideas and innovative events, unwavering in its commitment to the full inclusion and acceptance of peoples’ whole selves.

Elsa (L) and Karen (R) are two grant writing champs!

Additionally, there has been INCREDIBLE leadership from lay persons at OWC. Lay leaders have taken on the lion’s share of grant writing and are responsible for raising over half a million dollars for the renovation campaign! They are the TRUE ROCKSTARS!

Things happen slowly here, never all at once. Like root growth, relationship building takes time. When people are introduced to the space, I am clear that this space, and all the communities it engages, are messy. We don’t get it perfect or even close to right most of the time. And, of course, there is a whole bunch of grace.

We recognize that we are in this together. Everyone pitches in. There is a LOT of donations. Donations of time and talent: by the laity, by our community partners, by volunteer groups, and by building users. We’ve had the entire kitchen remodeled and food forest built up by just the time and talent of volunteers.

And, of course, the donation of stuff – so much stuff – from desks, chairs, filing cabinets for the co-working space, art supplies, inclusive children’s books picked up from around the city, dumpster rentals to get rid of other stuff, couches and rugs to better fill out the shared spaces, and gardening supplies, including a drip irrigation system, tool shed, and wheelbarrow among so many other things!

It is a messy, beautiful community full of messy, beautiful people and their messy, beautiful relationships doing their best to change the world.

A More Excellent Way16

Northeastern Student Volunteers Handing out Ice Water and Lemonade on the Hottest Day of the Year.

The church, in how it organizes itself, how it talks about itself, and how it structures its financial models, is in desperate need of resurrection. Many church models are outdated; our language, along with our ideas, are stagnant.

Old Testament theologian Walter Brueggemann challenges these issues, of outdated language and stagnant structures, in the contemporary church, inviting us to imagine what ministering, and being the church, in and with a resurrection mindset might look like. Instead of operating with our “tribal code” or church speak, we renounce our outdated linguistic “shibboleth” and allow ourselves to be transformed. We rejoice at outsider input. We celebrate change rather than shy away from it. Only when we allow the resurrection of our church to speak is our worldview enriched, our language expanded, and our expectations broadened. Only when we fully embrace a new, more excellent way, can we see the promise accompanied with the resurrection reality.

And resurrection must also be in our expectations and our measures of success. Despite our expectation for outsiders to take up our language in order to fit in, we rely on outside or worldly metrics of success that blatantly ignore the Christological and “evangelical metric… of the neighborhood.”17 Brueggemann invites us to embrace the foolishness, weakness, and mystery of Christ as a way of reimagining church, or, in truth, resurrecting the church in a manner that looks more like the kindom of God and less like some watered down version of Christ’s radical message. This message is one of deep hope: hope for the church and hope for the future. It promotes a radical hope that holds the contradictions and mystery of life, grounded in the resurrection. Christ’s “foolishness, weakness, and poverty” offer an incomparable “alternative to the deathly way of the world.”18 For God’s poverty will always be “richer than human wealth”19 and God’s foolishness always wiser than our own.20

Following Christ’s way, God’s foolishness, offers an alternative to worldly models. It invites the church to live into the resurrection mentality, bravely reimagining itself, embracing the diversity of God’s creation. For it is diversity that demonstrates the majesty of the Divine imagination made manifest in the created order. This is what success looks like in resurrection. Therefore, the moral imperative of the church is not to promote homogenous thinking, practice, or even worship, but to celebrate differences, allowing for creativity and promoting diversity.

The imperative is not homogeneity, but diversity. Diversity, of use, ideas, capacities, and persons, is at the heart of resilien·city. It incorporates all aspects of Jacobs’ vision for urban sustainability, all while nurturing a distinctly theological application of resiliency, the reality-based hope as Tippett so profoundly put it.

Besides better stewardship of space and resources, there is a theological impetus for this transformation. By transforming the way OWC imagines and “does” church, one can not only make a church and a space that is a little more just, a little more equitable, and a little more peaceful, but also a city, and perhaps a nation, that also has a little more justice, equity, and peace. And while all we are seeking to do is transform our little corner of the world, the gospel hope is that anything we do will make the space we inhabit look a little more like the kindom of God – and that in doing so, we might actively seek to empower the disenfranchised, lift up the broken-hearted, be a light for the world, and bring about the healing of the nations.

Your Invitation

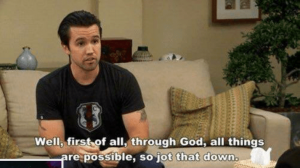

To those who say this impossible, I encourage you with the words of St. Mac from the gospel of “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia”:

But in all seriousness, I believe in resurrection.

I believe the church cannot sustain the structures and institutions it has created and held onto for decades. We need a reformation. We need a reimagination. We need a resurrection. I invite you to begin your own reimagining of space and identity for yourselves and your community.

OWC certainly is not the first, nor I hope the last, to undergo this admittedly difficult and inherently brave journey of resurrection. There are tons of amazing churches and pastors scrapping what institutions and powers have said is the way things have to be done. And in turn, they are creating beloved communities that truly look like the body of Christ, bringing about God’s kindom here and now.

Two of my favorites are led by two rockstars and friends. First is, LA First UMC, led by the incredible Mandy Sloan McDow. Worshipping without a building, creating space that is literally without walls, welcoming all, LA First is breaking down barriers, funding stunning and prophetic art installations, and truly rocking what it means to be the church in the world. Second is Greater Purpose Community Church in Santa Cruz let by the amazing Christopher VanHall. Christopher is not only pastoring the community but also creating a restaurant and brewery, sharing space with the worshipping community, and supporting it financially allowing the church to get rid of the problems of tithing.

If you ever want to contribute to the mission of OWC and/or resilien·city, check out the Donate button on our website.

If you want to continue the conversation, are interested in speaking more about how we found funding, or are looking for someone to help guide your church’s conversation, visioning, and journey, feel free to reach out.

And don’t forget: #DoJusticeLoveMercyHustleHumbly

About the Author

My name is Sara and I currently serve Old West Church. A transplant from Georgia, I come from a long line of Methodist pastors, including her mother and grandfather. My formal education includes an MDiv from the Emory University (2013) and a CTM from the University of Cambridge (2013). My CTM thesis dealt with examining the redemption of female sexuality through Christ’s resurrection in John. I am passionate about social justice, particularly as it pertains to equity for all genders, identities, sexualities, ethnicities, abilities, nationalities, family structures, and belief systems.

My spiritual gifts include yelling at racists, throwing away things churches hoard for decades in back rooms, rocking the boat, putting up sassy/snarky signs around my church, and organizing to tear down systems of injustice and oppression. Also, petting puppies.

Works Cited

- It is even better if they don’t have a family. Single and no family means they can devote all that extra time to the church, right? Hilarious.

- Lipka, Michael, “Mainline Protestants Make up Shrinking Number of U.S. Adults.” Pew Research Center. May 18, 2015. Accessed December 06, 2016. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/05/18/mainline-protestants-make-up-shrinking-number-of-u-s-adults/.

- Sojourners, “Parking Lot Church.” Accessed November 25, 2018. https://sojo.net/media/church-meets-parking-lot.

- OWC served as a safe house on the Underground Railroad. Abolitionists lived in the surrounding Beacon Hill community. This history made the West End an ideal place for African Americans to reside in Boston.

- Often called “The Last Tenement House.”

- Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. (New York: Vintage Books, 1992), 169.

- Rev. Thomas Gallan, letter to Sara Garrard. March 25, 2019.

- Growing with Hope, “About the Program.” http://www.growingwithhope.org/#/program/ (accessed November 12, 2018).

- Rendle is a senior consultant at the Texas Methodist Foundation.

- Gil Rendle, Waiting for God’s New Thing: Spiritual and Organizational Leadership in the In-Between Time – or – Why Better isn’t Good Enough (Austin, TX: Texas Methodist Foundation, 2015), 3.

- Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise: An Inquiry into the Mystery and Art of Living. (New York: Penguin Random House, 2016), 251.

- Ibid.

- The decision to use kindom and not kingdom is an intentional decentralization from the patriarchal language of kings and kingdoms, lords and lordship. This choice seeks to move away from male-centric language and move toward the focus on the community without any gender restrictions.

- Jacobsen, Eric O. Sidewalks in the Kingdom: New Urbanism and the Christian Faith. (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2003), 45.

- Besides hope, and peace, there is also a “love trumps hate” thrown in for good measure.

- Get it? It’s a pun. A bible pun. From 1 Corinthians 12:31. Hilarious.

- Walter Brueggemann, “Getting our Sibilant Right: The Evangelical Shibboleth – Judges 12. 1 – 16 and 1Corinthians 1. 10 – 13” Festival of Homiletics – San Antonio Texas. May 15, 2017.

- Brueggemann, “Getting our Sibilant Right: The Evangelical Shibboleth.”

- Ibid.

- 1 Corinthians 1.25, CEB

I am a retired UMC pastor in the NE Conf. Though my ministry is providing therapy in Lowell, and find myself dumbfounded of not knowing about your incredible ministry at Old West Church!! Wow!! Pass the word around anywhere you can! Post this on the Conf. web site.

Allan

Sara, this is amazing and wonderful! You are doing a great job in unexpected, welcoming and creative ways. Keep it up!

Nancy Powell, a fan