Believed to be somewhat autobiographical, Mama Tried offers Merle Haggard’s lament at the pain he caused his mother by his incarceration. Music historians note that Haggard, who did serve a short sentence at San Quentin in 1957, did not, as his famous song explains “turn twenty-one in prison doing life without parole” but nevertheless, the pain Haggard visited upon Mama is unquestionable to the listener. Haggard’s now-incarcerated subject acknowledges clearly that Mama tried to raise him better, but despite the “Sunday learning, to the bad, I kept on turning ‘til Mama couldn’t hold me anymore.” Arguably, Mama Tried is Haggard’s most iconic track in a large and important musical library that includes some of the better known and more polarizing songs of Haggard’s era. People fought over some of Haggard’s music, and much of his lyrics represent a cultural and political view not espoused or advocated in or for here or elsewhere, but Mama Tried is not one of those recordings. Since July of 1968 listeners and cover musicians alike have sung along with Haggard’s lifer who thinks back on his formative years at home, and in recalling the lessons from Mama (and Dada), now can see clearly where, despite how hard Mama Tried, their lives took a different direction. In March of 2016, the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress accepted Mama Tried into its catalog for preservation. Believing that its music and lyrics represented something worth preserving, Mama Tried will be saved future listeners. Merle Haggard died some fourteen days after his song of a son’s lament was preserved and deemed “culturally significant.”

This project is not about country music, Merle Haggard, nor the criminal justice system, but like the twenty-one year old looking back upon his childhood home and lessons taught there by his eponymous “Mama”, what our parents taught us, how they taught us, and how those lessons are or are not retained and authoritative is foundational, especially so as parents themselves. The 2019 Candler School of Theology Doctor of Ministry project entitled On Intentional Modeling: An Exploration of Communicating Values Concerning Money and Generosity to Young Children by their Parents that his summary blog represents finds a cultural touch-point in Merle Haggard’s icon music and lyrics. Like Haggard or his musical protagonist’s autobiographical confession, the crux of this project reflects the lessons we learned in our childhood homes, how they were taught to us, and it offers us a methodology for how parents of young children might think about passing on values to their children. The findings of this project might not have kept Mama’s boy out of prison but they do give us a way to intentionally and purposefully try.

Key Concepts at Work in On Intentional Modeling

To better understand the key concepts at work in On Intentional Modeling, and how they help parents of young children claim their important role in teaching values regarding money and generosity to their children, it is worth exploring some of the key concepts at work.

America’s Mrs. Manners Advice on Talking About Money

As American as Apple Pie and Baseball is the belief that you do not discuss religion, politics, or money in pleasant company. Such wisdom and practice likely originated far before 1952 and its acceptance did not originate with “etiquette adviser” Amy Vanderbilt’s advice published in Amy Vanderbilt’s Complete Book of Etiquette: A Guide for Gracious Living but Vanderbilt’s interpretation of the great American caution is worth noting. Gracious living insists that we refrain from open money talk for a variety of reasons and rationales but one stands out for the purposes of this project. Vanderbilt’s advice published in 1952, again in 1954, and remaining in print today, suggests that parents should educate their children on finances but only when those children are wise enough to navigate the social graces that assume money not be discussed openly or flippantly; a far greater faux pas for Vanderbilt’s 1950’s America. Considering that statistically the parents of current parents of young children were growing up themselves after Amy Vanderbilt’s Complete Book of Etiquette was accepted as authoritative, her words cautioning parents to avoid discussions about money with children seemingly too young to appreciate the difference between a fifty-cent piece and everything else of equal size and shape. In short, talking to your kids about money shouldn’t start too young lest risking the consequences of flippant social awkwardness.

Beating on Bobo and the Modeling of Behaviors

Beating on Bobo and the Modeling of Behaviors

Is Vanderbilt right? Should parents avoid talking openly about money to their children. Perhaps. Etiquette may require no money talk to young children but developmental psychology understands that speech is but one way parents educate their children. Enter Bobo, a punching bag that looks like a clown, and the theory of modeled behavior.

In the 1960s Stanford University psychologist Albert Bandura brought together a handful of young children, a Bobo punching bag doll, and adults who would show two different methods of playing with Bobo. For one group, the Adult pummeled Bobo, and for the other group, Bobo was treated well despite being a punching bag by design. The adults left, the children and Bobo remained, and the results are now, some fifty years since, not surprising. If the kiddos saw Bobo get a thrashing at the hands of an adult – a person imbued with authority by culture and custom – then Bobo caught many a hand by the youngsters. The opposite is true as well. If the children saw Bobo treated well, they treated Bobo well. Published as Transmission of Aggression Through Imitation of Aggressive Models in The Journal of Abnormal Psychology in 1961, Badura’s work is a cornerstone of how On Intentional Modeling approaches its signature question: how do we effectively communicate values regarding money and generosity to children. Vanderbilt may suggest that we refrain from speaking about money to young children, but Bandura finds the other side of teaching and learning: young children picking up behaviors and norms from adults, namely parents and in the home.

Is Young Ever Too Young to Start Thinking About Modeling?

The designation “Young Children” is found across developmental theories and textbooks all the world around, and often the age range is in disagreement. Deciding when children are “young children” is a matter of choice in a trusted source such as the Center for Disease Control which treats “Young Children” as a macro category ranging from infants to eleven years of age. Somewhere within the first eleven years, one might summarize would be the right time to start teaching kids about money and what their parents believe can be done with it, but when exactly is the so-called right time to start thinking intentionally about how modeling will educate your child and acting accordingly? The answer might surprise you. According to Psychologist Alan Fogel, the first chapter of a child’s life, infancy is the appropriate time for parents to begin thinking and modeling with intentionality. Fogel describes infants as “participants” in “the cultural community” found within the environment they inhabit – like that of the home – and children less than one year old and up are learning from parents and household participants how navigate the world offered to them. If children are learning social cues and truths from parents in their first months then is it ever too early to start thinking about how our behaviors and actions are teaching our kids how to understand the world? The answer seems to be no.

Parents, the Home, and the Future Our Kids will Inherit

Bringing the diversity of concepts and conversation partners together is important in order to signal clearly to parents of young children that what we offer our children through words and lived-out behaviors will help form their understanding of the world and how to live in it. Nobody does that heavy lifting better than social researcher and author Laurent Parks Daloz in his easily understood research synopsis entitled Can Generosity Be Taught? Speaking to over one hundred people who have demonstrated through often self-sacrifical actions that they are committed to the common good of their communities and beyond, Daloz and his associates found that such an outlook on life did not happen by accident. Those who exhibited an understanding of how pro-social behaviors such as generosity could make the world a better place learned those behaviors most reliably and most often at home and not only at church or school. Institutions like church are vital in reinforcing the lessons of home but all the Sunday school in the world won’t be nearly as effective as parents who model generosity, gratitude, and values regarding money to their children day in and day out. Furthermore, Daloz makes it quite clear: parents and those like parents far more than Pastors, Teachers, and the like will have the greatest educational impact on children and their inward adoption of pro-social behaviors that will make the world better. We cannot outsource our children’s modeled education if we want those kids to live out a value-driven life when it comes to money and generosity. The world our children will inherit, filled with needs both familiar and new, and entrusted to the children we now raise need parents to seriously consider how they will teach what is true and good. It is the opinion of this project that intentionally and thoughtfully modeling the pro-social behaviors of generosity and gratitude, and corresponding values of money and its uses is how we put our children in the best place to do noting short of change the world for the better.

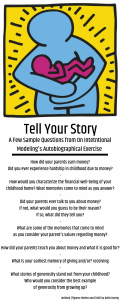

Getting Parents to Tell Their Story: The Method of On Intentional Modeling

How do the conceptual building blocks of modeling and developmental abilities of young children; the cultural road blocks of American etiquette expectations; and the data driven findings of Daloz that pro-social values are taught at home by parents come together in On Intentional Modeling? The answer is simple: provide an opportunity for parents of young children to explore their childhood and lessons found there regarding money and generosity, and tell their story. Willing participant parents of young children were guided through an autobiographical exercise sometimes called a Philanthropic Autobiography. Questions were created, provided to the twenty-five parents of young children representing thirteen families, and asked during an interview session conducted often in the parent’s homes. Of these twenty-five parents of young children participating in this project, they represent age ranges from thirty-three to forty-seven; have between one and three children; are both married and single; range in education from some college to terminal degree; all are white and heterosexual; were raised in households where religion and participation in a faith community was either tolerated or advocated; and were raised by their biological parents in either one or two parents households. Of the twenty-five participants, some their households includes step-parents, half brothers or sisters, and the like. Unlike many demographic markers of the participants, financially our group represented a common diversity among parents of young children. Financial earnings for the households represented were described in a variety of ways ranging from struggling with the inability to save, to comfortable, to among the top earnings individuals in the state of Wisconsin; the location of this study. While there were many commonalities among our participants, the nature of their finances was wildly diverse.

American etiquette expectations; and the data driven findings of Daloz that pro-social values are taught at home by parents come together in On Intentional Modeling? The answer is simple: provide an opportunity for parents of young children to explore their childhood and lessons found there regarding money and generosity, and tell their story. Willing participant parents of young children were guided through an autobiographical exercise sometimes called a Philanthropic Autobiography. Questions were created, provided to the twenty-five parents of young children representing thirteen families, and asked during an interview session conducted often in the parent’s homes. Of these twenty-five parents of young children participating in this project, they represent age ranges from thirty-three to forty-seven; have between one and three children; are both married and single; range in education from some college to terminal degree; all are white and heterosexual; were raised in households where religion and participation in a faith community was either tolerated or advocated; and were raised by their biological parents in either one or two parents households. Of the twenty-five participants, some their households includes step-parents, half brothers or sisters, and the like. Unlike many demographic markers of the participants, financially our group represented a common diversity among parents of young children. Financial earnings for the households represented were described in a variety of ways ranging from struggling with the inability to save, to comfortable, to among the top earnings individuals in the state of Wisconsin; the location of this study. While there were many commonalities among our participants, the nature of their finances was wildly diverse.

To get a sense of the power behind this narrative claiming and naming exercise, here is an abridged exercise that you are encouraged to experience either by yourself or alongside your parenting partner. Intended to encourage honest reflection and discussion, do not undertake this exercise believing there to be a “right answer.” The best answer for you is your honest answer. To experience the full list of questions used in On Intentional Modeling please click the link for a downloadable PDF.

If you took the time to engage the sample autobiographical questions, or found yourself answering every question of the full list linked above, what was your experience? Were you able to answer every question immediately, clearly, and without much hesitation? Were you crystal clear as to your parent’s values regarding money? Did you know for sure the charitable impulses of your parents and why they gave generously or otherwise? If you answered YES, then you are unique. Every one of the twenty-five parents of young children interviewed for this project hesitated, struggled, found recollections foggy, or otherwise absent regarding their parents’ underlying values regarding money and generosity. Clear were their memories of Christmas mornings giving and receiving gifts. The stories recalled from trips to Grandparents or the time Mom or Dad helped a neighbor during a crisis were crystal clear as if from just yesterday but, nearly universally, current parents of young children struggled to share a story whereby Mom or Dad or both sat them down and explained their operational values regarding money and generosity. This autobiographical exercise was formed in such a way as to force an engagement with what was or was not made crystal clear in childhood regarding money and generosity, and to get the participant to consider not just what they learned but how they learned.

The Modeled Lessons of Childhood:

Findings from On Intentional Modeling

After reviewing nearly a thousand minutes of recorded transcripts featuring the memories and stories, processing and drawing conclusions of how their own parents taught their values, a clear trend began to develop among our participating parents of young children.

Children rarely know what their parents believe regarding money, its uses, and the values behind it.

It was clear to the participants growing up in the household of their parents that Mom, Dad, or both worked, and that profession provided financially for the family. Some knew if Mom or Dad had a job that paid well, and some were kept intentionally in the dark, but overall, regardless of an appreciation of family finances, outside of the bills being paid, food in the fridge, and the necessities of a family, most of participants had no true understanding for how money was treated or understood by their parents. Why parents may have saved their money over spending; why parents spent their money over saving; and generally what values regarding money were foundational or operational for their parents remained a mystery.

Despite the absence of clearly articulated values regarding money and generosity, whatever lessons were taught or discerned from childhood remain mostly intact and authoritative in adulthood.

This single fact stands out as arguably the most important of the entire body of findings for its ability to underscore the core argument of the entire On Intentional Modeling project. If these twenty-five participants and their uninterrupted adherence to the values they came to understood as taught to them by their parents, not by vocalized instruction, but through unintentional modeling, then it stands to reason how impacting modeling truly is for teaching children pro-social behaviors. When the participants had ever consciously rejected a lesson or a value regarding money or generosity that they believe was modeled by their parents, other than the obviously negative lessons imparted such as shame and or willful ignorance, participants could not name a childhood value regarding money or generosity that they did not think still valid for their lives.

Values and lessons about generosity were hard to come by in comparison to similar lessons regarding money.

If the values behind the modeled lessons regarding money that stand out still to the participants, those having to do with the value of generosity were even more elusive. Whereas most participants could cobble together a theory of how their parents might answer the prompt “money is good for…”, virtually nobody could describe the values of generosity in their household. What was observed was often check writing to churches or charities, but such observations, even those offered to children intentionally, were nearly never accompanied by an explanation as to why the household gave to the church or the Red Cross. Neither was the giving of time and skill made clear to our participants by their parents. Families were gathered together from time to time and brought to a neighbors home to help in an emergency or in a time of loss, but such actions were rarely explained. Left up to the children to decode, gifts of time and talent made an impact but were almost never a clear product of a deeply held value.

What is remembered regarding generosity is the giving of time and skill.

Every participant could recall a story, often a found one, of a time when Mom or Dad pitched in and helped the members of their community however they understood it. Among the stories shared during the some one thousand of minutes of interviews, we find the stereotypical kinds of ways people with skills, time, talents, or resources unavailable to another share them freely in times of need. Such examples, though rarely explained, and rarer still rooted in language of value, remained in the memories of participants, and they clearly made an impact. It is clear from listening to the participants that when parents give of their time and skill to others, that example, is highly instructive. Considering the above finding that values perceived and discerned from within the childhood remain authoritative, it should not be surprising that the participants when prompted shared their own understanding that giving of time and skill to the needs of the community made a greater impact and were of greater value than the giving of money alone. It is clear from these interviews that modeled behaviors regarding sharing skills and time are among the most instructive.

These common findings among our twenty-five participants paints a clear picture. Children are often left to their own devices, interpretations, and misunderstandings regarding their parents’s values regarding money and how those values inform their actions. Piecing together an often disparate collection of experiences filled with inconsistencies and head scratching moments, the children represented in this study could have benefitted greatly from modeling that was truly intentional. One only has to imagine if a parent who understood and appreciated the nature of childhood learning in the home made a conscious decision to educate their child in both word and deed so as to insure that if asked, their child might be able to clearly extoll the virtues and values at work regarding money and generosity in the household. Such an impact clearly appears to be multi-generational and could cascade down the family tree for decades to come. In short, if parents of young children accept the gift given to them in understanding how they themselves were molded largely without forethought and intention, and how such modeling educated them for a nearly lifelong understanding of money and generosity then imagine what a different could be made in the lives of their children and future generations if these parents of young children modeled intentionally. Such is the dream of this entire project and the entire reason behind undertaking the study presented in On Intentional Modeling.

Resources Cited

Amy Vanderbilt. Amy Vanderbilt’s Complete Book of Etiquette: A Guide to Gracious Living. 2nd ed. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1954.

Bandura, Albert, “Transmission of Aggression Through Imitation of Aggressive Models”. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 1961

Daloz, Laurent A. “Can Generosity Be Taught?” Essay on Philanthropy, No. 36 (1998)

Fogel, Alan. Developing through Relationships: Origins of Communication, Self, and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993., pg. 34