For years, I have followed the career of Dr. Miranda Bailey on ABC’s medical drama, Grey’s Anatomy. I have always been amazed by her intelligence, her leadership, her work ethic, and her wisdom. She is the epitome of what one might perceive to be a strong black woman. As a fan of the show I have watched her character develop from a resident to the Chief of Surgery. However, at the top of her game she tells her husband she needs a sabbatical from her marriage, and she also proclaims she needs a sabbatical from her high demanding job to do research. She needed a break from the responsibilities from being chief. This leads her to hiring her former student, Alex Karev to be the Interim Chief of Surgery. Although, she fights for the opportunity to breathe and take off her Superwoman Cape and just be for a season, she finds herself stepping in during a storm and saving the day once again. But, then something interesting happens as she is in the midst of saving everyone else, she realizes she needs saving. Check out the clip.

This scene was a reminder of the need for Black Women, specifically Black Clergywomen to have a space to say, “I am not ok” and “I need help.” The first African-American Clergywoman that I witnessed both privately and publicly admit that she was not ok was Pastor Juanita Rasmus of St. John’s Downtown in Houston, Texas. In 1999, she and her husband Rudy were serving a congregation of about 3000 members when she experienced what she names as “the crash” or the “great depression of 1999.” At that time, she was teaching two Bible Studies every week, providing food and services for the homeless, working with families affected or infected by HIV/AIDS while working to raise her two daughters, as well as trying to maintain a healthy marriage. She tells the story of how one morning she was up preparing to take her girls to school and getting ready in the bathroom, when her husband calls out to her and says, “take your time I’ll take the girls to school today.” In that moment she was elated to not be the mom in the carpool line putting on makeup.But, while in the bathroom, she felt sick to her stomach. She called her secretary and told her, “I’m not feeling well, I’m going to lay down and come in about noon.” A few minutes later, she called her secretary back and told her, “I’m not coming in and I don’t know when I will be in. I think I’m going to take a sabbatical or something.” She then returned to bed.

That was the start of what old folks used to call a “nervous breakdown,” but the clinical term is a major depressive episode.[1]During this season of depression, Juanita, a typically faithful woman found herself sleeping for 18-20 hours a day. She tried to read her bible and pray; but, for some reason she just could not do it. One day, after an exhaustive effort of trying to get out of the bed and feeling as if she was paralyzed, she heard the Holy Spirit say, “Look at you Juanita, you can’t do anything for me, but I love you.” She heard the voice in a judgmental tone because she had always experienced God as judge. But God was saying it a different way, He was saying it softer and lovingly “Look at you Juanita, you can’t do anything for me, but I still love you.” Although, it took therapy, medication, prayer, and meditation, I think the biggest part of her healing came in those quiet moments in her bedroom, where God spoke, “look at you, you can do nothing for me but I still love you.”[2]

Courageous Conversation

The following video is a courageous conversation between Pastor Juanita and myself discussing her crash, vulnerability, therapy, how medication played a part in the healing process, the importance of sharing one’s story, and the redemptive power of God.

Her vulnerability really struck a chord with me. After listening to her testimony, reading a blog of a seminary classmate, and reflecting on my own journey I recognized an unhealthy trend: all three of us had suffered from depression while serving God and The United Methodist Church. It did not matter how gifted, intelligent, or anointed we were, this mental health issue negatively affected every area of our lives from our sleep patterns, to our familial relationships, to our relationship with God. Each of us had to discover our own paths to health, wholeness, and reconciliation with God. Additionally, each of us had to navigate the stigma attached to being vulnerable and saying out loud that “Everything is not fine.” There are perceived consequences of sharing mental health issues, i.e. being labeled as crazy or as a problem, feeling a sense of dis-ease over possible loss of position, or loss of privacy when one takes off “the mask that grins and lies.”[3]

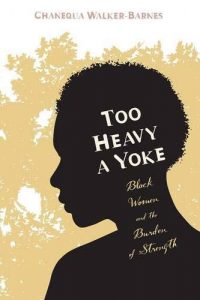

Thus, it became important to me to provide a safe place for a small group of African-American clergywomen within the Texas Annual Conference (TAC) of The United Methodist Church to take off the mask, be vulnerable, and to do what Jephthah’s daughter and her girlfriends did in Judges 11:29-40, as well as what the widows who surrounded the body of Tabitha in Acts 9:36-43 which is to mourn—to lament, to holler. Lamenting is complaining to God with the expectation that God will intervene in one’s circumstances. But, when lament is placed in the mouths of African-American women, it becomes a holler. It is a cry that comes from the depths of their bellies that names injustice and oppression but presses toward a hope that can only come from a redemptive God. Therefore, in my research I will seek to answer the following questions: Why is it necessary for clergy, specifically African-American clergywomen to engage in grief work? What can African-American clergywomen discern about God and their own agency through a black liberationist and a womanist reading of Judges 11:29-40 and Act 9:36-43? What are some strategies that African-American clergywomen can employ to combat feelings like everything is an effort; thereby combating the Superwoman Schema? How can the creation of safe and sacred space for sharing one’s story be a place for mourning and healing to occur? The purpose of this project is to prevent a small group of African-American clergywomen from the Texas Annual Conference from silently and privately suffering from emotional and spiritual pain by engaging in practices of mourning: lament and holler in order to foster wholeness and community.

Why Lamenting and Hollering are Necessary

Old Testament scholar, Patrick D. Miller argues that “the laments of Scripture make clear what is present in every human cry for help, the assumption that God is there, God can be present, and God can help.”[4]Essentially lament is “the voice of pain and the voice of prayer.”[5]When lament is put into the mouths of African-American women it becomes the holler. A. Elaine Crawford states that

Holler is the primal cry of pain, abuse, violence, separation. It is a soul-piercing shrill of the African ancestors that demands the recognition and appreciation of their humanity. The Holler is the refusal to be silenced in a world that denied their very existence as women. The Holler is the renunciation of racialized and genderized violence perpetrated against them generation after generation. The Holler is a cry to God to “come see about me,” one of your children.[6]

By lamenting and hollering, African-American clergywomen can give voice to their pain in order for freedom and release to occur.

This path to freedom and release seems simple enough, yet, there are systemic challenges to wholeness that African-American clergywomen face. The Clergy Health Initiative at Duke Divinity School performed a study in 2008 on 95% of the United Methodist pastors (1,726) in North Carolina to gauge their level of mental health.[7] Based on the results 8.7% of clergy who took the survey by phone were deemed depressed. Additionally, 11.1% who took the survey either online or by paper were deemed depressed, which is double the national average.[8]According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, African-Americans are 10% more likely to report experiencing serious psychological distress when compared to non-Hispanic whites. 9.9% of Black women report that everything is an effort.[9]There is obviouslya problem with the rising rate of clergy depression as well as the demands on African-American women. Unfortunately, many African-American women take on the yoke of the Strong Black Woman or Superwoman Schema. Chanequa Walker-Barnes contends that the StrongBlackWoman is

Driven by a deeply ingrained desire to be seen as helpful and caring, she is practically incapable of saying no to others’ requests without experiencing feelings of guilt and worthlessness. As her willingness to help repeatedly reinforces others’ tendencies to ask her for help, her very nature becomes defined by multitasking and over-commitment. A modern day Atlas, she bears the weight of her multiple worlds upon her shoulders. And unfortunately, she is as incapable of saying “help” as she is of saying “no.” …Thus, fearful of being seen as unfaithful, the StrongBlackWoman invests considerable effort in maintaining the appearance of strength and suppresses all behaviors, emotions, and thoughts that might contradict or threaten that image. Even as the physical and psychological toll of her excessive caregiving mount up, she maintains a façade of having it all together and being in control.[10]

While Cheryl Woods-Giscombe argues that the Superwoman Schema is:

(1)perceived obligation to present an image of strength, (2) perceived obligation to suppress emotions, (3) resistance to being vulnerable or depending on others help, (4) motivation to succeed despite limited resources, and (5) prioritization of caregiving over self-care.[11]

Because of this tendency black clergywomen need a space to share their stories of pain and triumph in order to contend both with the pressure of trying to be superwoman while attempting to break the stained-glass ceiling and remain whole. By creating a space where lamentation can occur black clergywomen have the ability to claim that despite the oppression they may face in the church and in the world—in the space they create— they are free; they are whole; and, they are connected to the redemptive power of God.

The Project & The Research Process

African-American clergywomen need a place to mourn—to weep, to lament, to holler and share their stories. Depression and burnout are real issues that clergy face but, for various reasons many are afraid to address them. Some are afraid of being transparent and vulnerable. Others are afraid of seeking and engaging in professional counseling. Some are afraid that if one is public about his/her issue, the cost could be the next appointment/promotion (within United Methodist circles). Some do not want their congregations caring for them when they accepted a call to care for the church. I understand that I cannot eradicate depression and burnout among all African-American clergywomen, but I can provide a haven for a small group of African-American clergywomen from the Texas Annual Conference (TAC) of the United Methodist Church to share their pain and loss as well as their story—the good stuff and the bad. It is through the telling of their story wholeness and healing can occur.

Although, clergywomen as a whole wrestle with issues of depression, burnout, and stress; there is little research that exists on African-American clergywomen and mental health. I specifically focused on African-American clergywomen in the TAC not just because they wrestle with the pressure of taking on the yoke of the Superwoman Schema but, because of their involvement in a predominately white denomination in the south. The TAC has 746 active clergy, 246 are women and only 58 are black clergywomen.[12]The TAC is composed of nine districts and it takes about six and a half hours in driving from the top of the conference to the bottom of the conference. Thus, I tried to choose African-American women from various places within the conference, various age groups, as well as various lengths of service. I performed qualitative research. I used to the online tool SurveyMonkey.com to disseminate questionnaires via email. I sent out a pretest questionnaire to nine African-American clergywomen. The pretest questionnaire asked demographical information (age, how many years in ministry, ordained or not, etc.) in addition to questions surrounding hardships they have experienced due to race and gender. I also tried to gauge if members of the group feel that everything is an effort, their level of ministerial support, engagement with mental health professionals, as well as topics that the group would be interested in covering in their time together.

Following the questionnaire I facilitated four sessions with these women, three via the video conferencing site, Zoom and one in person session that included two members of the group video conferencing in because of the distance of the meeting. The sessions were structured: Check-in time (members of the group were given an opportunity to share joys and concerns), Centering time (music was played and participants were invited into breathing exercises, moments of reflection on the lyrics of the song, and prayer), Reflection on the Scripture text (Judges 11:29-40 and Acts 9:36-43), and Engagement of the topic of the day. The two topics we focused on were: Have you grieved your expectations of what you thought ministry would be? And Are you Black Superwoman?

The Impact of Judges 11:29-40 and Acts 9:36-43

I did extensive exegetical work outside of meeting with the women on Judges 11:29-40 and Acts 9:36-43. The Judges text is the story of Jephtha’s daughter and her girlfriends. Essentially, it is an account of what happens when the victim becomes the victimizer. Jephthah is the illegitimate son of Gilead. He is kicked out of his father’s house because he is not the son of Gilead’s wife. However, when the Gileadites get into trouble they seek him out to lead them into war. He in turns makes a foolish vow to God that if he has victory over his enemies that whatever or whoever comes out of his house first he will offer as a burnt offering. Jephthah’s daughter did what any young girl would do when her father was gone away for work or a trip, she runs out and greets him. Instead of being embraced she is given a death sentence. She takes the sentence on the chin and requests that she get two months to roam the hills with her girlfriends because she is a virgin. This account really struck me because, it spoke to what happens when you do not have control over your own destiny and when you have to trust in a person or in the case of black clergywomen within The Texas Annual Conference, a system. You are putting your trust both in God but also a system that wants you to produce– in the case of Jephthah’s daughter eventually children but, for black clergywomen fruitful ministry. And this account is what happens when things go awry. How do you recover? How do you recover when God does not stop the atrocity from happening? How can you swallow the pain? The story shows that Jephthah’s daughter finds solace within the comfort of the company of these girlfriends. In their space, she could be her authentic self. She could be angry. She could cry out. She could be vulnerable about her pain with women who understood that it could be them as well. I knew that the women who participated in my group had experienced trauma and drama because of being an African-American Clergywoman in The Texas Annual Conference. I knew that they understood that the pain that they experienced at the hands of individual churches and because of conference level decisions was not just felt individually but, felt communally. I wanted the women to understand that there was scriptural basis for entering into one another’s pain and grieving together. There was a need to make some communal noise, even if the noise only changed them on the inside and did not change the powers that be.

This account really struck me because, it spoke to what happens when you do not have control over your own destiny and when you have to trust in a person or in the case of black clergywomen within The Texas Annual Conference, a system. You are putting your trust both in God but also a system that wants you to produce– in the case of Jephthah’s daughter eventually children but, for black clergywomen fruitful ministry. And this account is what happens when things go awry. How do you recover? How do you recover when God does not stop the atrocity from happening? How can you swallow the pain? The story shows that Jephthah’s daughter finds solace within the comfort of the company of these girlfriends. In their space, she could be her authentic self. She could be angry. She could cry out. She could be vulnerable about her pain with women who understood that it could be them as well. I knew that the women who participated in my group had experienced trauma and drama because of being an African-American Clergywoman in The Texas Annual Conference. I knew that they understood that the pain that they experienced at the hands of individual churches and because of conference level decisions was not just felt individually but, felt communally. I wanted the women to understand that there was scriptural basis for entering into one another’s pain and grieving together. There was a need to make some communal noise, even if the noise only changed them on the inside and did not change the powers that be.

Acts 9:36-43 is the account of the resurrection of Tabitha. In this story we encounter widows who surround Tabitha’s body in the upper room. The believers in the community send for Peter to come and do something about her death because Tabitha was a disciple of Jesus (the only woman in scripture given this title) and her death effected the financial stability of her community. She took care of a group of widows. Therefore, when the widows weep because of the death of Tabitha, they are also weeping for their future. When Peter arrives in the upper room, they get in his face and show him the clothes that Tabitha had made. Different versions of the scripture speak about how they surrounded Peter or pressed into him. He gets a little annoyed and sends them a way. But, what I liked about these women is that they boldly got into Peter’s face because they understood if Tabitha was saved from her fate, they were saved as well. And when Peter raised her from the dead, Tabitha was presented back into the community and the widows rejoiced. I think it was important to show these African-American clergywomen that when one falls down and is able to get up, we need to rejoice with her. And even more importantly, there is something about collectively rising up against injustice and expecting God and the earthly powers to respond. I thought we needed to discuss the importance of a collective voice and how there is power when we (Black Clergywomen) come together and speak out. Additionally, there is power when we come together to celebrate how we got over, how we got through our trial and tribulation to testify to what God has done for us.

The Purpose of the Sessions

The purpose of the first two sessions was to get the African-American clergywomen to name that they had experienced grief while serving God and the church. I wanted them to name the tension between what they expected ministry to be versus the reality of what ministry actually was. In these sessions some named that they actually were in the midst of the grieving process. One participant said that ministry was “not what I expected but he expected me to follow through.” Another participant said, “my expectations weren’t as important as God’s expectations, in ministry there will be valleys and mountaintops.” There was a sense of obligation to God and the call that seemed to supersede participants feelings toward their current position. The third session was a pivotal one. Members of the group were introduced to Ellen Davis’ interpretation of lament before delving into Acts 9:36-43. After, discussing the importance of being in relationship with one another in times of trouble, these women were pushed to think about how they often respond in times of trouble like superwoman. Yet, in this case being superwoman was not something to be proud of. The invisible cape that many or all have worn at some point in the journey of life and ministry was a metaphor for the charac teristics of the Superwoman Schema. One said that the cape was “Covering Anticipated Perceived Expectations.” Many campaigned that the cape needed to be burned; yet in the same instance many of the participants forgot that they responded to yes and sometimes to the characteristics of the Superwoman Schema.

teristics of the Superwoman Schema. One said that the cape was “Covering Anticipated Perceived Expectations.” Many campaigned that the cape needed to be burned; yet in the same instance many of the participants forgot that they responded to yes and sometimes to the characteristics of the Superwoman Schema.

One participant in particular wrestled with the effects of how the Superwoman Schema played out within The Texas Annual Conference. She said “we are called angry black women when we express our emotions. We are not whole humans—3/5ths of a human. We don’t have as much importance.” Her words disturbed me so much that I sent her a separate email and she elaborated more on her feelings and this is what she said:

She was crying out from the depths of her soul against the injustice that was not just played out against her but every African-American woman who dealt with feeling like less than despite her calling by God. This email epitomized for me what Hollering was all about. Her comments bring us to some strategies that I named to combat the Superwoman Schema were:

- Don’t be afraid to holler.

“Holler is the primal cry of pain, abuse, violence, separation. It is a soul-piercing shrill of the African ancestors that demands the recognition and appreciation of their humanity. The Holler is the refusal to be silenced in a world that denied their very existence as women. The Holler is the renunciation of racialized and genderized violence perpetrated against them generation after generation. The Holler is a cry to God to “come see about me,” one of your children.”[13]

- Take the time to engage in the 5 steps of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

- Cultivate new Community- Do not silently suffer without saying something.

- Invite other sisters to mourn, to weep with you.

Then we brainstormed as a community how we could combat the Superwoman Schema collectively and individually. These were the results:

- Set your boundaries (professionally and personally)

- Stay True to Your Sabbath

- Celebrate little things for ourselves

- Your self-care needs to be celebrated by you

- Accountability partners

- Make sure to make room for the things you enjoy, get a hobby, have some fun, laugh,

- Occasionally go into a trusted session where you can have some deliverance on yourself (we can hurt and don’t know it).

- Use what’s being provided: We get 3 sessions a year for counseling a year and take an opportunity to take sabbatical even if you think you don’t need it.

The final session was in-person where stories were shared. Tears were cried, heartache was given a name, worship occurred, laughter rang, and support was felt.

After the experience of the four sessions a posttest questionnaire was given. This questionnaire assessed the level of the effectiveness of the use of technology, did the participants feel like they gained a sense of community, the importance of mourning, and further engagement with the scripture text.

Findings & Future Implications

After four sessions of exploring the questions: “Have you grieved the expectations of what you thought ministry would be?” and “Are you black superwoman?”, it is evident that there is power in mourning as the African-American clergywomen of the TAC delved deeper into the practices of lament and holler. They were able to fully grasp that lament is complaining to God and expecting God to respond to your problem or your pain. Through lament they were able to give voice to their pain and communicate to God through prayer. And yet, understand that lament does not leave us in a place of pain but pushes us toward praise. The women learned that lament put into the mouths of African-American women becomes a holler. The holler is a sound not only filled with emotion but, it is the cry that comes out of the depths of black women’s bellies. It demands to be heard. It brings to light injustice- racialized and genderized violence. It is a cry to God to be “the ever present help in the time of trouble.” For so long this cry has been stifled. Many of these women have been silently suffering with issues of anxiety and depression, because carrying the yoke of the StrongBlackWoman or the Superwoman Schema has held them hostage and prevented them from asking for help. Therefore, these women need spaces to be vulnerable and to engage in the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. These women need a place to name the pain associated with the inability to fulfill unfair expectations thrusted upon their shoulders due to their profession as pastors, their denominational and conference affiliation, as well as personal and familial demands.

The African-American Clergywomen of the TAC need a place to take off the mask and engage in story-sharing: unmasking, inviting catharsis, relating empathetically, unpacking the story, as well as discerning a way forward. These women need a reminder that within the Biblical narrative that they can locate stories of pain and redemption just like theirs. For instance in Judges 11:29-40 Jephthah’s daughter is sentenced to death by the foolish vow of her father but finds comfort within the community of girlfriends who mourn—lament and holler with her about the injustice of her fate. Jephthah’s daughter’s girlfriends understand that it could happen to them too. This narrative lets the African-American clergywomen of the TAC know that moments of unfairness and injustice may arise in your life and ministry but there is a sister on the journey who will enter into your pain, and her presence will demonstrate that we serve a God that does not leave us alone in the midst of trials and tribulations. Additionally, black clergywomen can examine the story of the resurrection of Tabitha in Acts 9:36-43 and become aware of what happens when the African-American clergywomen of the TAC band together, pray, cry out, lament, and holler. Things (structures and systems) can begin to change because the evidence is when the widows who are in the upper room surround Tabitha’s body, holler, and press into Peter, Peter responds by resurrecting Tabitha. It is through the resurrection, the redemption of one that all can experience victory. Thus, through the community that was created via Zoom the African-American clergywomen felt safe to be vulnerable, safe to explore how to take off their superwoman capes, and experience the support and encouragement from women who have experienced their pain. As they learned how to mourn—to lament and to holler they became free and were able to experience wholeness. In the sharing of their personal pain, the personal pain became the communal pain. However, when the pain morphed into praise there were other women waiting to praise God with them. But, when the pain could not turn to praise, there was someone there reminding them that there was hope that one day it would.

The next step is acknowledging that grief work continues. Providing spaces for African-American clergywomen to express how they really feel while offering support is crucial to the health and wholeness to them as well as the congregations that they serve. Additionally, I want to think through more what does restoration look like in these settings and how to foster it. I know lamenting and hollering bring release and can bring a sense of wholeness but, I want to explore how this space can be a place where transformation of thought, of spirit, of reaction can happen. I want this space to be a place where peer mentoring occurs in the midst of lamenting and hollering. However, that comes with trust and time. I look forward to continuing this journey with these women as well as others. There is something powerful when will lift our voices. I believe when we make some noise things begin to change either within us or within the systems we are a part of. There is a song by William McDowell called “Intercession” and in it he says, “The change I want to see must first begin in me. I surrender, so your world can be changed.” Therefore, as we get stronger within the communities that we create, we as Black Clergywomen become bolder in sharing our stories so that we can see change in us and the change in the world around us. It must first begin in us!

[1]According to the DSM-5 Companion for Counselors, Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is indicated by a constant, quite possibly daily “feelings of sadness and loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities. Many individuals will experience loss of appetite, fatigue, problems with sleep, and suicidal ideations.” MDD is characterized by “a single or recurrent major depressive episodes.” Stephanie F. Daily, Carman S. Gill, Shannon Karl, and Casey A. Barrio Minton. DSM-5 Learning Companion for Counselors. Alexandria, Virginia: American Counseling Association, 2014, 38-39.

[2]Juanita Rasmus, interview by phone Tori Butler, March 29, 2017.

[3]Paul Laurence Dunbar, “We Wear the Mask” in African-American Poetry: An Anthology, 1773-1927,ed. Joan R. Sherman (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1997), 64.

[4]Patrick D. Miller, “Heaven’s Prisoners: The Lament as Christian Prayer,” in Lament: Reclaiming Practices in Pulpit, Pew, and Public Square,ed. Sally A. Brown and Patrick D. Miller (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2005), 16.

[5]Ibid.

[6]A. Elaine Brown Crawford, Hope In the Holler: A Womanist Theology (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002), xii.

[7]The study does not take into account black female clergy. 90.9% of participants in the study were white and 74.7% were men. I think this study did a disservice to the diversity of the clergy that are in The United Methodist Church. I believe that this study would have been more helpful if done in a conference like the Baltimore Washington, North Georgia, or Texas Annual Conferences where there is a greater representation of African-American clergy serving. Andrew Miles, Matthew Toth, Christopher Adams, Bruce W. Smith, and David Toole, “Using Effort-Reward Imbalance Theory to Understand High Rates of Depression and Anxiety Among Clergy,” The Journal of Primary Prevention, vol. 34, issue 6 (December 2013), accessed February 23, 2019, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10935-013-0321-4#Sec15.

[8]Duke Today Staff,“Clergy More Likely to Suffer from Depression, Anxiety:Demands put pastors at far greater risk for depression than people in other occupations,” Duke Today (August 2013), accessed June 27, 2017, https://today.duke.edu/2013/08/clergydepressionnewsrelease.

[9]This statistic is derived from a chart that measures the percentage of non-Hispanic black women and their feelings of sadness, hopelessness, worthlessness, as well as feeling like everything in life is an effort. “Mental Health Status,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, last modified February 24, 2017, accessed June 27, 2017, https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=24.

[10]Chanequa Walker-Barnes, Too Heavy a Yoke: Black Women and the Burden of Strength (Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2014), 4-5.

[11]Cheryl Woods-Giscombe, “Superwoman Schema, Stigma, Spirituality, and Culturally Sensitive Providers: Factors Influencing African American Women’s Use of Mental Health Services,” Journal of Best Practices in Health Professions Diversity: Research, Education, and Policy9, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 1124-1144, accessed July 29, 2018,

[12]Nancy Slade, Administrative Assistance Office of Clergy Excellence TAC, e-mail message to the author, January 30-31, 2019.

[13]Brown Crawford, xii.