It is the contention of this study that many churches in North America are existentially threatened due to their loss of a viable role within the changing social and economic ecosystems of their communities. Isolated from the life-giving and restorative resources of the community’s ecosystems, congregations become increasingly disconnected from the people and institutions which sustain them.

Analysis of this isolation from the perspective of ecosystem theory, combined with the connectional leadership of boundary leaders, will enable congregations to regain a valued place within the community. This, I argue, will abate the decline of many congregations and enable an evolutionary path toward renewal.

Living on the Edge of the Ecosystem

First United Methodist Church of Palatine, Illinois is an example of a congregation that is poorly adapted to its current community’s ecosystems, exhibiting all the characteristics of social isolation, occupying a trivial role within the Palatine community.

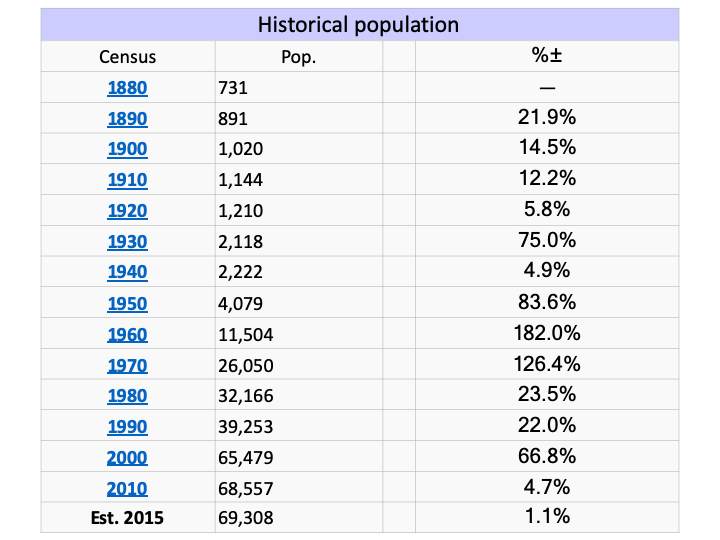

Following the end of World War II, the rural agrarian culture of Palatine was replaced by a more educated and affluent Protestant/Catholic post-war suburban population. This growth of suburbia quickly supplanted the rural characteristics of the community. With this change, First United Methodist Church transformed from a small country church to a large and growing congregation. The suburban culture of Palatine continued to reflect Western European culture and forms of worship. Thus, the congregation continued to grow without any significant change of culture or diversity.

Following the end of World War II, the rural agrarian culture of Palatine was replaced by a more educated and affluent Protestant/Catholic post-war suburban population. This growth of suburbia quickly supplanted the rural characteristics of the community. With this change, First United Methodist Church transformed from a small country church to a large and growing congregation. The suburban culture of Palatine continued to reflect Western European culture and forms of worship. Thus, the congregation continued to grow without any significant change of culture or diversity.

More recently, however, the Palatine community has undergone a significant cultural transformation. The Christian post-World War II community has been replaced by a new highly diverse and pluralistic culture which no longer reflects the uniformity of the Christian suburban culture of the second half of the twentieth century. Instead, Palatine is now a community of multiple ethnicities, religions, races and economic status.

After a century and a half of serving and reflecting the religious character of the Palatine community, mainline Protestant and Catholic congregations are receding in the wake of a vastly more pluralistic culture and society. The population in Palatine, according to 2016 estimates, is approximately 64% Caucasian, 13% Asian, 19% Latino, 2% African-American and 2% Racially Mixed.[1] The Caucasian population, furthermore, has shifted in its ethnic balance toward Eastern European populations. Palatine has also divided into economic segments of the population which has resulted in a growing sense of class and racial division.

Thus, the members of First United Methodist Church are becoming increasingly aware that their traditional social ecosystems and religious ecologies no longer exist. How might they respond to this situation?

A Useful Metaphor

Today the concept of ecosystems is ubiquitous in ecological and business thought. Ecosystem theories have proven critical to the understanding and guidance of both natural and business environments. Given this interpretive and strategic success, I suggest that we adopt and extend the concepts and vocabulary of ecosystems to the field of church analysis. I believe that the metaphorical use of ecosystems will provide important insights and guidance in the study of church life, identity, and strategic management. The success or failure of many churches may depend on their ability to understand and guide the role of the church in their changing social environments.

Ecosystem thinking as applied to businesses (Deloitte Insights).

While certainly not the only valuable theory, ecosystem theory is a uniquely useful way to consider the church. It is not a theological or biblical approach. Ecosystem theory is silent on ecclesiology and polity. It does not address worship or liturgy. It does not ask or answer the most important questions concerning the nature and identity of the church, but it does help to assess and evaluate the relationship of the church to the community. It orients the church within its environment and challenges it to effectively engage the people, organizations, and institutions of the community. It provides a path out of social isolation, which so many churches find themselves, and suggests ways the church might both give and receive.

Social Ecosystem. A relational community supported by a foundation of interacting organizations (churches, schools, businesses, government, etc.) and individuals. This community seeks to provide the goods and attain the goals and social objectives which are valued by the community. Over time, the members of the community, which include the constituent organizations and individuals, will coevolve their capabilities, roles, and identities, seeking to align themselves with the changing objectives set by the community. Those organizations and individuals which hold leadership roles may change over time, but the function of ecosystem leadership is essential because it enables members to move toward shared visions by aligning their efforts and finding mutually supportive roles.

Social ecosystems can be small and narrow in purpose or large in scope and number of participants. Thus, churches can participate in a range of ecosystems from the entirety of the community to small and temporary projects. In this study, we are concerned with all forms, given that churches participate in a wide range of social ecosystems. Yet, it is the more comprehensive social ecosystems which connect the church to the people and culture of the community. These community-based ecosystems are often determinative of the survivability of a church and congregation.

An Example of Ecosystem Building

Prior to my appointment to First United Methodist Church, I was the pastor of Marengo United Methodist Church in Marengo, Illinois, a small rural community with a reputation for bars, gun stores, video gambling, and empty storefronts. Following the recession of 2008, the community of Marengo experienced increased levels of poverty and social degradation that left the community in a state of economic and social despair. Needing a sign of hope and social renewal, nine area churches came together to found “Faith and Family Day.” This event brought together churches, businesses, government and social organizations to create an annual festival event in downtown Marengo. Organized by the Marengo Clergy Association, this event was intended to provide hope and inspire the community to build and restore the community’s social values. Working as a group of boundary leaders, the church leaders brought together a wide array of organizations around a shared purpose, accomplishing something that could not be achieved in isolation, benefiting all who were a part of this new ecosystem. The Marengo-Union Times described the event in 2015 in these words:

It was marvelous to see Marengoans from all the churches in town, as well as people not belonging to one, come out and celebrate a day together. If one of the goals of Faith and Family Day was to boost community moral, then by all means it was a success.

Much thanks must be acknowledged to all the volunteers who helped the event run as smoothly as it did, all the performers who graced the stage, the local restaurants and stores that came out to highlight their work, the churches who worked together to make the day happen, and of course everybody who came out to support.

The importance of having events such as this in town, with the goal to bring the community together, cannot be overstated. Here’s hoping for another fantastic Faith and Family Day next year, and perhaps even some other community events inspired by the example set![2]

The Marengo United Methodist Church proved to be an important part of the social and economic ecosystems of Marengo by bringing together organizations and residents around the unifying values of community, faith and family. It was a celebrated success in the life of the Marengo community and demonstrated the need for other such events.

“Faith and Family Day” included nine churches, over one hundred volunteers, local and regional bands, one international Christian artist (Danny Gokey), stage crews, crafters, game rental companies, local merchants and restaurants, corporate sponsors, waste services, the Park District, the local radio stations and newspapers, government, police, and the mayor who sponsored a pig roast. Each person or organization had an important reason to be a part of this event. Some were not there to support the organizing purpose of the event, but all had an interest in its success. The partners did not relate to each other competitively, but sought an opportunity to bring their special talents, gifts, and valued contributions together to invest in an event that was meaningful and socially significant.

Recognitions at the first “Faith and Family Day” in Marengo, IL

As an example of social ecosystem building, the efforts around the creation of “Faith and Family Day” demonstrate the five basic components of social and economic ecosystems.

Fundamental Components to Social and Economic Ecosystems

Unifying Social Purpose

- Focus on a purpose that addresses a need or pain in the community.

- This must be a purpose shared by a significant portion of the community, justifying the creation of an ecosystem.

- It must be worthy of sustained attention and commitment by a network of ecosystem participants.

Complimentary Partnerships

- Identify partners who can contribute to the attaining of the shared goal or purpose of the ecosystem.

- Build a network of those partners specifically adapted to complement each other’s contributions.

- Leverage these relationships to achieve the unifying purpose of the partners and community.

Spirit of Collaboration

- Build a connection between the unifying purpose and the network of partners.

- Sustain their commitment by emphasizing the benefits they will enjoy by working together.

- Dissuade partners from disruptive, competitive or controlling actions.

Coevolution of the Partners and System

- Respond to the changing conditions between the partners of the system.

- Respond to any changes in the goal or purpose of the ecosystem.

- Evaluate the wider ecology in which the ecosystem exists.

Boundary Leaders and Institutions

- Boundary Leadership is required to create and sustain an ecosystem.

- Care – Boundary leaders feel the pain of brokenness and perceive the opportunity to solve a problem.

- Imagination – Boundary leaders are able to envision new possibilities and novel solutions to these problems.

- Connectional Intelligence – Boundary leaders are able to build the network of relationships necessary to achieve imaginative visions.

- Resilient – They are able to endure the opposition that is inevitable when challenging the status quo

Boundary Leadership

Boundary leadership is the key component. Ecosystems and churches depend on leaders who can both identify opportunities to do something valuable and connect them to the array of resources, people and organizations necessary to realize this value. They are leaders who are drawn to issues that matter most in life. When they find an opportunity to change things for the better, they push against the boundaries that prevent the solving of a problem and providing a sense of hope. Boundary leaders “create webs of transformation, in which their own hope and own responses resonate with the hopes and responses of others, and they create in that resonance patterns of new relationships.”[3] Boundary leaders, in other words, move us from purpose to hope, and from hope to relationships, and from relationships to the realization of our hopes. They are a rare and necessary type of leader. But who are they?

Boundary leadership is the key component. Ecosystems and churches depend on leaders who can both identify opportunities to do something valuable and connect them to the array of resources, people and organizations necessary to realize this value. They are leaders who are drawn to issues that matter most in life. When they find an opportunity to change things for the better, they push against the boundaries that prevent the solving of a problem and providing a sense of hope. Boundary leaders “create webs of transformation, in which their own hope and own responses resonate with the hopes and responses of others, and they create in that resonance patterns of new relationships.”[3] Boundary leaders, in other words, move us from purpose to hope, and from hope to relationships, and from relationships to the realization of our hopes. They are a rare and necessary type of leader. But who are they?

They are individuals who care about improving upon life. Rather than working from the center of things, boundary leaders “are attracted to the broken, and broken-open, spaces in between formal structure and ‘legible’ functioning.” “Boundary leaders emerge because the force of life draws them out and up toward the vital arenas where the future is trying to be born.”[4] They do not believe in the status quo and the permanence of things. Instead, they seek out the pain and brokenness of what exists to “create opportunities to nurture the new for the sake of the whole.”[5] This can be seen in economic and social ecosystems. Boundary leaders search on the edges of life for gaps and opportunities to “make things better.” They are constantly seeking to reform what “is” into what “ought to be.”

They are able to do this, in part, because they have the capacity to think imaginatively. “In the boundary zone,” writes Gary Gunderson, “imagination is what makes it possible for webs of transformation to emerge out of chaos.”[6] “Imagination,” he describes, “is the magnet around which relationships form in ways that resonate and then reinforce the images of hope before that hope is visible.”[7] This distinguishes the difference between natural and human ecosystems. For, as James F. Moore writes, “social systems are composed of real people who make decisions,” and those decisions depend upon “a powerful shared imagination, focused on envisioning the future.”[8] “Unlike anything in biology,” he argues, “shared imagination is what holds together economies, societies, and companies.”[9] In the creation or evolution of any ecosystem there are always boundary leaders who “capture the moment,” and are able to share their imaginative and hopeful visions with others.

Boundary leaders also possess what is often referred to as connectional intelligence. Imagination must be coupled with connectional intelligence if the ecosystem is to be formed and sustained. Moore argues this point when he writes: “You need to design business relationships to bring in the most powerful players and contributions, and they must be choreographed into a dance that provides dramatic new benefits for customers.”[10] According to Moore, it is not enough to imaginatively form a hopeful vision of the future. “You want to provide the architecture for large-scale cooperation. In a sense, what you are doing is a form of community organizing. You are forging new economic relationships.”[11]

Finally, boundary leaders are resilient. They must be, given that they are agents of change, and often threaten the status quo in order to achieve either the renewal of an ecosystem or disruption of the existing order to establish new social or economic structures. “Institutions, by contrast, tend to set boundaries and to police them, creating lines of command and accountability defined in terms of those boundaries.”[12] “Boundary leaders appreciate ambiguity, not just as something to be endured, but as the experiment in which hope bubbles out of the test tube.”[13] This hope, however, often comes at a price as fear and defensiveness meet the boundary leader “head-on” or more likely in acts of sabotage. Boundary leaders, according to Gunderson, must be tenacious and tough.

An introductory explanation of Boundary Leadership

Reconnecting First United Methodist Church

Gathering the existing and potential boundary leaders at First United Methodist Church, we have worked to reacquaint the congregation with the community and expand their sense of self-identity by taking small steps into the boundary zone between the church and community. We have sought to build small webs of transformation.

- The first was building a close relationship with Boy Scout Troop 209, the largest and most innovative scouting organization in the Palatine area. After insisting that we support the troop in building and launching an experiment to the International Space Station, I accompanied the troop to Cape Canaveral for the launch of the experiment. Developing this relationship has resulted in a significant and growing connection between the church and the scouting community.

- After years of denials by our Board of Trustees, we have constructed a community garden. This highly visible outreach to our community and neighbors has helped shift the vision of our church. We have followed this up with hosting community meals and participating in public events. Thus, issues concerning the needs of our community and neighbors are no longer alien to the congregation.

In an attempt to widen the focus of the congregation, we have developed a relationship with a Methodist church in San German, Cuba. To date, we have contributed over five thousand dollars and collected numerous bags of physical goods that are in short supply in Cuba. These items have been transported by members of our congregation on numerous visits to the island. My intent in developing this relation was not only to help the people of San German, but to open First United Methodist Church to the world.

In an attempt to widen the focus of the congregation, we have developed a relationship with a Methodist church in San German, Cuba. To date, we have contributed over five thousand dollars and collected numerous bags of physical goods that are in short supply in Cuba. These items have been transported by members of our congregation on numerous visits to the island. My intent in developing this relation was not only to help the people of San German, but to open First United Methodist Church to the world.

- Most recently, the congregation has established a partnership with the Children’s Dyslexia Center of Chicago. Searching for a location in the northwest suburbs of Chicago, we have made available to the Dyslexia Center six classrooms and office space. Underutilized space is now devoted to helping children with disabilities, opening the church up to the community by providing actual contact and care. Rather than closing the church at 3 pm, we remain open and engaged in ministry from 9 am until 8 pm, Monday through Thursday.

- We have even welcomed a Baptist church into our contemporary space on Sunday mornings. Embassy Church is not only a source of needed financial support, but we are forming a partnership in community ministries, social activities and worship. Despite our theological differences, we seek to find places of commonality where we can work together as Christian congregations in support of our shared communal interests.

Through these and other efforts, First United Methodist Church has begun to play an increasingly significant part in the social ecosystems of Palatine, demonstrating examples of boundary leadership and connectional intelligence. In an article, for instance, from the local newspaper, The Daily Herald, a new identity has begun to emerge in the community and consciousness of the congregation.

First United Methodist Church board member Greg Burnett of Inverness said Children’s Dyslexia Center will be good for the region. He’s led the effort for the church to become partners with the organization.

“Community service and outreach is a really, really big part of our church,” Burnett said. “And when the dyslexia center approached us about possibly partnering with us to be able to utilize our facilities, we took a good look at the dyslexia center and found it’s just an excellent organization.”[14]

Review and Conclusions

In churches like Marengo United Methodist Church, I have witnessed the renewal of the church through the building of social ecosystems; and I am beginning to perceive hopeful signs at First United Methodist Church. The church is exploring new ways to collaborate with others. It is building relationships and partnerships with other people and organizations around shared social goals. With the steps into the community listed above, a change of congregational leadership, and new supportive staff, the church is beginning to reflect forms of boundary leadership. Hope is reemerging and an adventurous spirit is returning to the church. This, I believe, has the potential to lead the church into new boundary zones of discovery where First United Methodist Church may find its place in a transformative ecosystem, discovering a new identity and social purpose.

This hopeful process of building and joining ecosystems will need to continue at First United Methodist Church. My research is far from complete. The fate of the church is unknown and the results of my work in boundary leadership and ecosystem theory are indeterminant. The greatest benefits of ecosystem analysis and leadership are yet to be definitively observed. Hence, there is a need to apply more time and boundary leadership to continue the journey and assess the results of this study.

What can be positively asserted, however, is the value of joining James F. Moore’s work on ecosystems with Gary Gunderson’s ideas on boundary leadership. Moore’s work on ecosystems calls for a theory of leadership which is approximated by Gunderson’s definition of boundary leadership. Conversely, Gunderson’s ideas of boundary zones and leadership require a more coherent explanation of the process and product of these ideas. Ecosystem theory provides a clarifying conceptual framework for boundary leadership resulting in a useful analytic theory of the church and social ecosystems.

I consider ecosystem theory, therefore, to be worthy of further development. This study has touched upon the potential of this “useful metaphor.” Yet, I believe it possesses vast unrealized potential to elucidate the social characteristics of the church enabling congregations to navigate the ever-changing environments of their communities and cultures.

Endnotes

[1] “Races in Palatine, Illinois (IL) Detailed Stats,” City-Data.com. Accessed March 15, 2019, http://www.city-data.com/city/Palatine-Illinois.html.[2] “Another Fantastic Faith and Family Day,” The Marengo-Union Times, August 4, 2015, accessed March 14, 2019, http://www.marengo-uniontimes.com/news/1689-another-fantastic-faith-and-family-day.

[3] Gary Gunderson, Boundary Leaders: Leadership Skills for People of Faith (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004), 20. [4] Gary R. Gunderson and James R. Cochrane, Religion and the Health of the Public: Shifting the Paradigm, (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012), 120. [5] Gunderson, Boundary Leaders, 83. [6] Gunderson and Cochrane, Religion and the Health of the Public, 138 [7] Gunderson, Boundary Leaders, 97. [8] Ibid. [9] James F. Moore, The Death of Competition: Leadership & Strategy in the Age of Business Ecosystems (New York: Harper Business, 1996), 11. [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid., 54.[12] Gunderson and Cochrane, Religion and the Health of the Public, 130.

[13] Gunderson, Boundary Leaders, 94. [14] Bob Susnjara, “Dyslexia center to open Palatine campus,” The Daily Herald, November 20, 2018, accessed March 14, 2019, http://www.dailyherald.com/news/20181120/dyslexia-center-to-open-palatine-campus.

| What is your Unifying Social Purpose?

|

| Who are the Complimentary Partners?

|

| How do you create a Spirit of Collaboration?

|

| How will you encourage the Coevolution of the Partners and the System?

|

| Who are your Boundary Leaders or Institutions?

|