Ethnography, Conflict, and Pastoral Care and Leadership

Introduction

As pastors and church leaders, we have all been there. You have a plan, a vision for how to lead the church to address a current crisis in the world today and how the church could respond. You develop what you believe to be is a balanced approach. Then the hammer falls. You are confronted with a hostile reaction and totally caught off guard. What now? Before you compose your resignation letter, take a deep breath. You are not the first to encounter conflict in ministry, and certainly will not be the last.

I serve two rural southern churches. There is lots of farmland, and everybody is related to one another. These family churches can trace their lineage to the area back as much as nine generations. They are representative of the white, conservative, Christian, dominant culture found throughout much of the rural south.

In the summer of 2020, I sought to address the racial tensions following the death of George Floyd and how the church might respond. The negative backlash to my sermons was swift and caught me off guard. The same folks I have enjoyed fellowshipping with, praying with, laughing, and crying with, were now unknown to me. Our worldviews could not have been further apart. What I thought was a moderated invitation to conversation was labeled by some in the congregation as “non-biblical” and “dangerous.”

Explanation of the project and research process

Ethnography may not be the first place to turn to when the going gets tough in your ministry context. Learning more about the people in your ministry context as well as the local history can be an invaluable asset for any pastor or church leader. My goal was to find a way to navigate through the brokenness and hostility between me and my congregations, maintain my pastoral presence and leadership with my congregants, while also remaining true to my own personal identity and theological integrity.

Before we can really bring people to the table to have difficult conversations, we need to listen. Ethnographic research involves listening to the words you hear, and to the words you do not hear. Ethnography identifies the stories and events that have shaped the people in the community you serve. Looking back through the generations and inquiring about the narratives and assumptions underlying the ethos of the church and community can be an eye-opening experience. So how and where to begin?

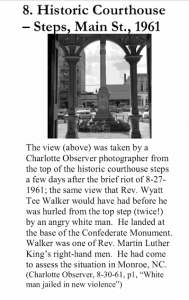

Your Local Library

Most local libraries will have a collection of books and materials covering the history and events of your ministry context. In my local library, there is an entire room dedicated to preserving and maintaining the local history. The research librarian proved to be an invaluable resource pointing me to newspaper articles, books, and materials on my specific topic of racial tensions in my ministry context. Civil Rights Activist, Robert Williams, born in Monroe NC advocated armed black resistance to white supremacy in direct contrast to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s much more publicized non-violent movement. In 1961, a group of Freedom Riders arrived in Monroe to provide alternative to William’s advocacy of armed resistance. They began teaching non-violent protest methods to area youth. A peaceful march around the Union County courthouse devolved into an overwhelmingly violent assault on the protesters by area white supremacists. I have lived in Union County for the past 14 years, and in North Carolina all my life. I was never taught any of this history in school and would never have known apart from my research for this project.

Online Resources

Refining your online search becomes the biggest challenge. Start with local websites such as the County Government, Chamber of Commerce, and local historical societies. I found social media groups to be highly informative as many of the participants were local and shared personal photos, stories, and insights.

Demographic Data

Through a database called MissionInsite, I was able to identify shifting patterns of ethnic diversity in my ministry context not readily visible within the walls of my church. Educational information provided by the local high school revealed that while recent graduation rates are increasing, prior decades show a significant majority of adults in the area hold a high school diploma or less. The family farmlands in my ministry context are becoming less sustainable and job growth is moving away from the area. Shifting economic, educational, and ethnic trends are directly impacting the people in my community. All of these factors contribute to the anxiety and fear people experience. The existential crisis of identity resulting from these changes shapes how they see the world around them and how they respond.

http://https://vimeo.com/538739651

One on One Interviews

While each individual story is specific to their context, those stories provide anecdotal evidence to give texture to the larger demographic data. Interviewing people not represented by the majority can provide insight and counter narratives to the more familiar stories and interpretations of history by the dominant culture. The Covid 19 pandemic of 2020 limited my ability to conduct many of the interviews planned for this project. One key interview for my research conducted in June of 2020 brought forth new insight from three Black men in my ministry context, two of whom were born and raised in Union County. The interview provided a sharp contrast to the more familiar histories and publicized narratives of the white dominant culture.

http://https://youtu.be/Z3QJQbt90X0

Interview with John Deese, Travis Deese, and Bill Caddell. Conducted by Mark Curtis, June 2020

http://https://vimeo.com/526306351

Interview with John Deese, Travis Deese, and Bill Caddell. Conducted by Mark Curtis, June 2020

Interpretation

Crucial to the ethnographic research process is the self-awareness of one’s own context, bias, and cultural perspective. As a white southern Christian male born and raised in North Carolina and having lived most of my life in rural areas, I am representative of the dominant culture in my ministry context. One example of this self-awareness came from the interview. I have had the privilege to not think about my ethnicity whereas the three men I interviewed made it clear that they are constantly aware of their surroundings and how their ethnicity is perceived by those around them.

Working within the limitations of the pandemic proved challenging, preventing me from empirical surveys of a wider range of people in my ministry context. As a result, I was unable to directly show how historical events shaped peoples narrative self-understanding today and how the demographic changes lead to the fear and anxiety present and the resulting clash of worldviews taking place within the discussions in our churches.

However, I have been able to navigate the past year more effectively as a direct result of my research. As an ethnographic practitioner of my ministry context, I gained empathy for the people in my congregations. Rather than dismissing them as caricatures, I began to see and hear more deeply. Even though I vehemently disagree with much of their social and political worldview, I believe I can better understand the why.

My ethnographic research led to empathy. And empathy is something we all need in this journey through life.