Looking Back to Move Forward: Navigating the Impact of Nostalgia on Church Growth in Rural Methodist Congregations

“Do not say, ‘Why were the former days better than these?’ For it is not from wisdom that you ask this.” – Ecclesiastes 7:10

An Introduction

Arriving at my new ministry location at the height of the global COVID-19 pandemic, I met with many congregation members who shared their expectations of worship and ministry when in-person worship returned. Many offered great insight but were grounded in longing for a perceived past that didn’t seem consistent with what the previous pastor described as their typical service or ministry. “Today, children are too distracted,” one older member opined. “They should sit on the front row so that the minister can watch them and make sure they are attentive. They should learn to appreciate sitting quite in the service and singing the old hymns like I did when I was a child.” The impact of nostalgic attachment the member held for their past worship and ministry experiences was clearly based on distorted memories and an obstacle to developing current plans for church growth and community outreach.

-Nostalgia-

Nostalgia is mostly a positive emotional experience that “entails revisiting cherished memories of persons and events.”[1] Unlike stored memories, nostalgia is the experience of pleasure or sadness caused by memories from the real or perceived past combined with a desire to relive the “remembered” event, no matter how distorted or unreliable it may be.[2] In the situation above, the congregation member was allowing their desire to relive their personal emotional attachment to memories of their past to influence their current expectations of ministry.

The individualization of personal nostalgia can be limiting when it is over-relied on leaving the accuracy of memories distorted and unreliable. However, communal nostalgia has been shown to serve a number of productive functions for the individual and community in building and strengthening interpersonal relationships.[3] Research has found that nostalgia influences our social connections and goals, our well-being, and overall life satisfaction.[4] “The thing that ties them all together,” observes Dr. Krystine Batcho, “is that nostalgia is an emotional experience that unifies.”[5] It is the overreliance on personalized nostalgia and the limited acceptance of communal nostalgia that forms a struggle for church growth and community outreach in my ministry contexts.

-Ministry Contexts-

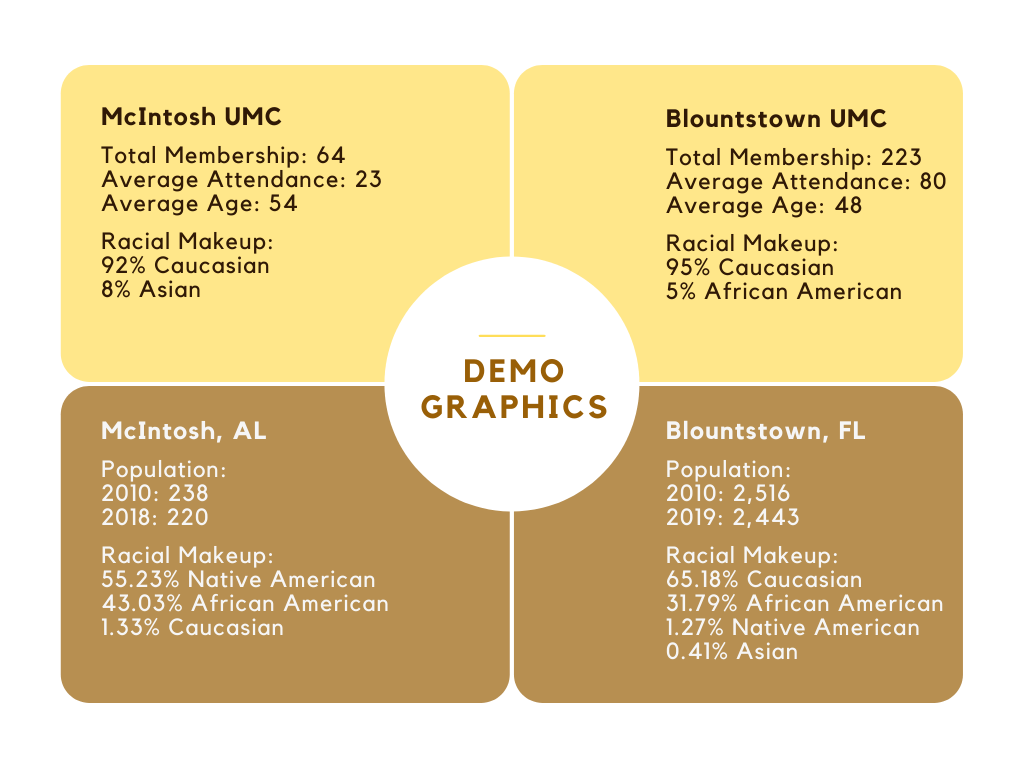

About a year into my research, I was transferred from a United Methodist Church in rural Alabama (McIntosh UMC) to a United Methodist Church in Florida (Blountstown UMC). McIntosh UMC is a small-town family church in McIntosh, Alabama that continues to be comprised of descendants of two main families. Blountstown UMC is a traditional Methodist congregation found in Blountstown, Florida located in Liberty County.

These two ministry contexts present similar challenges to church growth that center around nostalgic longing influencing congregation members’ approach to worship and outreach (as illustrated in the above situation) while sharing in the desire for church growth, especially among younger community members. This has led to concerns regarding the impact of nostalgia on their ministry and growth in the face of the overall decline in the Christian church. Many of these concerns include attempts to canonize one style or genre of music, and more time devoted to protecting old practices than considering new ones with leadership decisions being made based on how they best represent and perpetuate the past.

These two ministry contexts present similar challenges to church growth that center around nostalgic longing influencing congregation members’ approach to worship and outreach (as illustrated in the above situation) while sharing in the desire for church growth, especially among younger community members. This has led to concerns regarding the impact of nostalgia on their ministry and growth in the face of the overall decline in the Christian church. Many of these concerns include attempts to canonize one style or genre of music, and more time devoted to protecting old practices than considering new ones with leadership decisions being made based on how they best represent and perpetuate the past.

The Project and Process

This project utilized Dr. Batcho’s Nostalgia Inventory and a standard Tenets of Christian Faith and Church Satisfaction Survey to explore if church growth can be positively impacted when leadership engages the shared nostalgic longing of parishioners in developing ministry centered around community outreach. This information was also compared to participants’ understanding and acceptance of the basic tenets of the Christian faith. The survey and inventory results were analyzed between generations to distinguish shared nostalgic longing and satisfaction with the modern church worship experience differences between generations.

The participants in this study were from three pools of participants, Blountstown UMC, McIntosh UMC and volunteers from a university setting that self-identified as members of the “spiritual but not religious” group (SBNR), which served as a comparison group on the Nostalgia Inventory only. The participants were also placed into four generational groups based on their age: “young adult” (24 and below), “adult” (25-44), “middle age” (45-65), and “older adult” (66 and above).

Given the limitations placed on social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic and the health safety of many of the high-risk participants, direct contact was supplanted using direct mailing, email, and online surveys. This eliminated the option for group discussion and follow-up with participants directly with in-person contact and discussion.

Findings: Looking Back to Move Forward

Research has shown that nostalgic longings for the past could function as an inhibitor to change (personal nostalgia), or a facilitator for social connections that have the potential to bring generations together (communal nostalgia).[6] The findings of this study support these conclusions. The results of the Nostalgia Inventory showed an elevated nostalgic score across all generational groups above the average for the Inventory. Interestingly, the “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR) group’s Nostalgia Inventory average was higher than those in the religious-affiliated groups. This indicates a consistent nostalgic longing between the religious-affiliated and those who are spiritual but claim no religious affiliation. This is a clear area for further exploration.

The results for the generational age groups indicated that the strongest nostalgic longing was with the “young adult” group, with the “older adult” group registering the lowest. These results were reversed for the Tenets of Christian Faith and Church Satisfaction Survey with the “young adult” group reporting the lowest church satisfaction with its adherence to the tenets and the “older adult” group scoring the highest level of satisfaction.

-Looking Back to Move Forward-

Research has shown that nostalgia is a highly social emotion that bolsters perceptions of connectedness with others and is a resource that facilitates help-seeking.[7] The results of the surveys indicate a desire to look back to a time when the church engaged the community in a manner that fostered social resilience and personal connectedness. This is even more true among young adult respondents who desire a nostalgic longing for a better church community today while stressing the relationship between community outreach and the tenets of the Christian faith.

The results indicated that neglecting previous generational experiences creates a hollow ministry without the depth of the past. The benefit of nostalgia in ministry is that it brings generations together in building a more effective and meaningful experience in worship and discipleship. Author Todd Hunter encourages the rediscovery of ancient Christian practices a “repracticing.” He writes that “when I embarked on a search to find ways to make the habits of Christianity and church significant and valuable, I used the old as a launching pad for repracticed new.”[8]

Reliance on nostalgic experiences of past worship experiences, or even a romanticized nostalgic vision of early Christian church practices, maybe an indicator that parishioners are not satisfied with their current experience and are trying to reshape their ministry location to satisfy their nostalgic longing. The impact of communal nostalgic longing combined with the desire for more meaning or satisfaction in the modern worship practices of the Christian church presents an environment that church leadership could explore and build on in developing plans for ministry outreach and growth.

When developing plans for church growth and outreach, church leadership would benefit from approaching a discussion with parishioners focusing on understanding their satisfaction with their church’s ministry along with their degree of communal nostalgia. An effective plan of action to address the distinction between “personal” and “communal” nostalgia that allows church leadership to incorporate shared nostalgic experiences with ministry and community outreach should include open multi-generational discussion and feedback. Multi-generational discussion groups that challenge “personal” nostalgic longings would allow productive fellowship across generations in building on former worship experiences from older members while recognizing the demands and cultural differences impacting younger members. Exploring common ground founded on the foundational tenets of Christian faith and the shared needs of parishioners would foster a healthy worship environment while promoting community outreach and church growth.

[1] Abeyta, Andrew A., Clay Routledge & Juhl, Jacob. (2015). Nostalgia as a Psychological Resource for Promoting Relationship Goals and Overcoming Relationship Challenges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 1029

[2] Ibid.

[3] Newman, D. B., Sachs, M. E., Stone, A. A., & Schwarz, N. (2020). Nostalgia and well-being in daily life: An ecological validity perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(2), 325–347; Ye, S., Ng, T. K., & Lam, C. L. (2018). Nostalgia and temporal life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 19(6), 1749–1762.

[4] van Tilburg, W. A. P., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2019). How nostalgia infuses life with meaning: From social connectedness to self‐continuity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49(3), 521–532.

[5] Luna, K. (2019, November). Speaking of psychology: Does nostalgia have a psychological purpose? American Psychological Association. Retrieved July 6, 2021, from https://www.apa.org/research/action/speaking-of-psychology/nostalgia.

[6] Juhl, J., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Xiong, X., & Zhou, X. (2021). Nostalgia Promotes Help-Seeking by Fostering Social Connectedness. Emotion, 21(3), 631-643.

[7] Ibid., p. 631.

[8] Hunter, Todd. Giving Church Another Chance. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2010), 32.