Introduction to Ministry Context

The First UMC of Torrington was originally erected in 1843 in downtown Torrington, Connecticut. In 1965 it was moved to its current location a few miles away from the original location. The Church has been a beacon of the gospel, worshiping and working together to carry out God’s mission no matter what they have encountered with God’s help. I have served FUMC since July 2021. As a Korean American, I immediately observed a lack of diversity in the congregation, and in the community in terms of age, ethnicity, and race. The population is aging and lacks diversity.

Through MissionInSite[1], I have gathered demographic data about the studied area which is the city of Torrington in Connecticut. In terms of Ethnicity in the Torrington area, 90 % of the population is White, 5.3 % is Hispanic/Latino, 1.7% is Asian, and 1.3% is Black/African American. People concern most about financing the future/saving/retirement, day-to-day finance matters, fear of the future or the unknown. The interesting finding is about religion. Most people do not participate in religious organizations because they think that religious people are too judgmental. They consider religion to be too focused on money. They do not trust organized religion and religious leaders. They do not believe in God. They do not find religion to be relevant to their lives

I have observed that as a faith community, First United Methodist Church also lacks diversity in terms of practices of spiritual discipline. They have not often met for communal prayer. Members are not comfortable with praying publicly, instead of designating a few people (such as lay servants, the lay minister, and the pastor) to pray on their behalf in worship, in small group meetings, and during other fellowship events. However, I have observed that many members believe in the power of prayer, the necessity of prayer, and who have a deep desire to pray, but lack confidence in the practice of prayer or know only one way of praying.

In a community where a lack of diversity is prevalent, the majority of people do not believe God and do not trust religious leaders. So:

- What could the church do to initiate conversations among people?

- What could be effective ways to listen and stir the conversation?

- What could the church offer to people who have struggled to pray and who have not been exposed to various spiritual disciplines for their spiritual health, strength, and maturity?

- Why does the church need to offer various options and opportunities to congregations as well as the community to find out their ways to experience God and deepen their faith in God?

As Korean American woman clergy, who served a Korean immigrant church as well as United Methodist churches in the suburbs of New York and Connecticut, I have observed in both contexts a common problem: the lack of visual stimulation in an assortment of spiritual disciplines, Christian education, and worship.

The church has ignored the fact that each individual is created with multi-sensory and multi-intelligence[2] for learning, communicating, and worshiping. Marjorie J. Thompson says, “Spiritual disciplines must be freely chosen.”[3] Yet The majority of churches in the State regardless of size, location, race, ethnicity, or social-economic status, they have not provided various spiritual disciplines that congregants can freely choose, but are limited by scarce options. Congregants should be given many choices, the liberty of spiritual discipline as they strive for finding their ways to God, and the clergy has responsibilities and privileges to provide various means that stimulate human senses and intelligence and to meet the congregants’ spiritual needs for spiritual growth.

Humans experience and learn about God in various ways. humans have different types of learning: visual learner, auditory learner, and kinesthetic learner. However, people at the local churches engage in learning about God through text, underutilizing image although often image is a powerful method, especially for those who are visual learners.

I believe that the church needs to introduce and provide various spiritual disciplines to seek God and share their faith in the faith community in this twenty-first century, where people are exposed to numerous images and easily accessible to them.

Thus, I want to introduce a new prayer practice, Visio Divina, as a way to encourage and enrich their prayer lives in a non-threatening way. Yet in welcoming, accepting manners despite different perspectives of God in the church and community where a lack of diversity is prevalent.

Explanation of Project and Research Process

I reintroduce in my project the ancient monastic prayer of Visio Divina, a meditative and contemplative form of prayer that incorporates images for the believer’s visual stimulation and imagination.

Before practicing Visio Divina with church members, First, I introduced the ancient monastic prayer practice called Lectio Divina during last year’s Advent season through a four-week long session, because Visio Divina has all the components of Lectio Divina—lectio, meditatio, oratio, and contemplatio. There were three participants in this prayer group, out of over seventy Sunday worship attendees. They told me that they had not heard and did not know anything about Lectio Divina. Each session lasted for an hour, in which participants listened to the word of God, reflected on the word of God, responded to God by prayer, and rested in God. Most of the hour was filled with silence and deep breaths. These experiences were very new to all of them, yet all prayed for about an hour at each session, which was not usual for them at all. One of the participants commented that it was an excellent exercise showing the value of quiet meditation in which we asked the Holy Spirit to speak to us. The challenge was to focus our wandering minds and to spend time coming to a deeper understanding of what the scripture was saying. This participant appreciated being introduced to a new practice and was eager to incorporate the practice into his prayer life. Lectio Divina was the foretaste of Visio Divina, promoting interest and informing different ways of prayer.

The Practice of Visio Divina

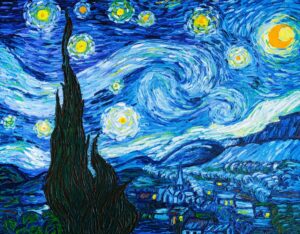

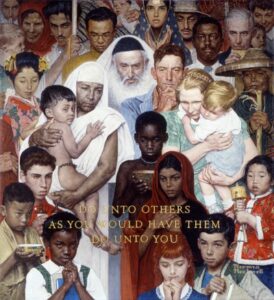

After a four-week session of Lectio Divina during the Advent season, I offered Visio Divina for a three-week session. There were three participants in attendance and those sessions were offered via Zoom due to Covid-19 and treacherous winter conditions in New England. And also many images are available online. I said some introductory words about Visio Divina’s origin and explained its six movements, which all participants followed with some further explanation and guidance. The six particular movements I used are based on Stephen J. Binz’s book, Transformed by God’s Word. I chose six movements because participants had already experienced Lectio Divina, so I figured the practice would already be somewhat familiar and not too taxing for them. I have experienced that Visio Divina is an effective method for spiritual discipline through which participants can have the following benefits: Soaking oneself in deep, silent prayer, strengthening imagination/ recognizing the power of imagination, accepting other’s perspectives, stirring conversation among believers for joyful, meaningful fellowship, and developing lay leadership. The first session’s Scripture passage was 1 Corinthians 13:4–7 with a photo by an unattributed photograph.The second session’s passage was 1 Corinthians 15:12–20 with the painting, Starry Night, by Vincent van Gogh.The third session’s passage was Matthew 7: 12-13 with the image, Golden Rule, by Norman Rockwell.

In each session, we gazed at the image while I asked the following questions:

“What do you notice in this image? What attracts you in this image? What repels you in this image? What emotions, memories, thoughts, or questions come up? Do you have any bodily sensations in response to the image and the memories, thoughts, and questions? What scriptures come to mind? Where do you see yourself in this image? Where do you see God in this image? What is happening in your life that is reflected in this image?”[4]We started the session with breath/Jesus prayer to quiet participants’ hearts and to center ourselves in the presence of God. I read the short Scripture slowly three times while participants sat comfortably in their homes.

I have researched how much the artworks are powerful as means of opening the hearts and minds of people as much as beyond words themselves. And also I have researched why images have not been used in the protestant churches.

Interpretation: Findings & Future Implications

I have learned and observed that as images can be viewed and interpreted in numerous ways in the practice of Visio Divina, biblical texts also have different meanings and can be viewed and interpreted in a variety of ways. Richard Jensen in Envisioning the Word states that “Narrative criticism is a relatively new tool for studying the Bible. One of its central elements is that biblical texts have a surplus of meaning. Biblical texts speak differently to different readers/hearers.”[5] However, sometimes the differences in biblical text interpretations are not well accepted and not embraced in theological conversations. During my observation in the sessions of Visio Divina, I have learned that images open up and stir up conversations among participants about what they felt, thought, understood, and heard. One participant said that “I see it as a creative way to create conversation in a group.” Participants embraced others’ different perspectives and experiences as they were without any judgment and enjoyed diverse perspectives. While Scripture is often viewed in one dimensional, sculptures or any artworks are easily viewed in multiple dimensions. The Practice of Visio Divina can be used in a way that “the arts open up opportunities for multiple shared interpretations of the text.”[6] And its practice helps people to accept and embrace others’ different interpretations and perspectives as “Art reveals in a unique and accessible way the polyvalency (multiple meanings) of Scripture.”[7] The practice of Visio Divina certainly enables people to listen and embrace others’ perspectives and generates a space of interactive and inspirational conversation, joyful fellowship through images and words of God.

Catholic Biblical Scholar Stephen Binz says, “In recent years, Lectio Divina has been liberated from monasteries and religious houses to become the heart of lay spirituality…Visio Divina is undertaken by lay people throughout the East, through the liturgy of the Church and also through personal prayer at the home.”[8] Visio Divina is one of the spiritual disciplines through which laity’s spirituality can not only be strengthened, deepened, and broadened but also their leadership can be stimulated and developed. It is an effective discipline, but a simple spiritual discipline by following steps in which mind, heart, emotion, imagination, will, desire are needed to seek God rather than a vast knowledge of God, Scripture, and Christianity. Through Visio Divina, reading the Word of God can involve gazing at images, contemplating in silence, and sharing their own perspectives beyond current contemplative practices centered on readings.

- Lucas Cranach, the Altar Triptych,1547, Church of St. Marien, Wittenberg, Germany

- The Altar at FUMC Sanctuary

Appendix 1: Six movements of Visio Divina[10]

- Lectio is best described as listening deeply to scripture as we read. We savor the word of the sacred literature, appreciating the images, envisioning the scene, feeling the sentiments, and allowing the words to move from our heads to our hearts. We read slowly and carefully, studying the words and characters, the images and metaphors.

- Visio is gazing upon an image, trusting that God will illumine our minds and hearts through the image. We look at the image not as spectators but as participants in the relationships and holy actions that the image evokes.

- Meditatio is reflecting on the meaning and message of the sacred text and the sacred image. After listening carefully and gazing attentively, we let the text and image settle within us and penetrate the deepest parts of our being. We let the encounter awaken within us new understandings, questions, and challenges. Our reflection forms connections between the ancient forms of the Gospel and our contemporary lives.

- Oratio is a verbal and prayerful response to God’s word as experienced in the sacred text and icon. If we have truly listened and gsed as God is revealed to us in words and images, we will naturally wan to respond to God. In this way, lectio divina and visio divina become a kind of dialogue with God, as we receive God’s word and respond to God in prayer.

- Contemplatio is simply a quiet resting in God. There arrives a time in our verbal prayer when words become unnecessary and no longer helpful. Our spoken response has taken us as far as it can in our relationship with God. Contemplatio is wordless silence in the divine presence We simply receive the transformation embrace of God who has led us to this moment.

- Operatio is faithful living in Christ. Lectio divina and visio divina lead not only to a changed heat but also a changed life. This practice must make a difference in the way we live. Operatio is the word of God lived out in generous service, in concrete witness, in faithful commitement, and in works of mercy.

Citations

[1]MissionInsite which is community engagement specialist for faith and nonprofit groups. Navigate to: MissionInsite.com

[2] Howard Gardner, Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons (New York: Basic Books, 2009)

He suggests that all people have different kinds of intelligences such as musical, body-kinesthetic, logical-mathematical, linguistic, spatial, interpersonal, intrapersonal intelligences. “It is of the utmost importance that we recognize and nurture all of the varied human intelligences and all of the combinations of intelligence.” p. 24

[3] Marjorie J. Thompson, Soul Feast: An Invitation to the Christian Spiritual Life (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014), xi.

[4] Therese Kay, Meeting God through Art: Visio Divina (North Haven, CT: independently published, 2019), 19–20.

[5] Richard Jensen, Envisioning the Word: The use of Visual Images in Preaching, with CD-ROM (Mineapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2005), 99.

[6] Ofra Backenroth, Shira D Epstein, and Helena Miller, “ Bringing the Text to Life and into Our Lives: Jewish Education and the Arts,” Religious Education 101, no. 4 (2006): 467, quoted in Maren Sonstegard-Spray, “Reading the Bible with Rembrandt: Graphic Exegesis in Christian Education” (D. Min., Thesis, Candler School of Theology, 2019), 11, accessed February 10, 2022. ProQuest.

[7] Doug Adams, “Changing Patterns and interpretations of Parables in Art,” ARTS 19, no. 1 (2007):5-13, quoted in Sonstegard-Spray, “ Reading the Bible with Rembrantdt,” 10.

“Adams adopts the term ‘polyvalency’ to mean multiple interpretations.”

[8] Stephen J. Bins, Transformed by God’s Word: Discovering the Power of Lection and Vision Divina (Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria Press, 2016), 20.

[9] Lucas Cranach, the Altar Triptych,1547, Church of St. Marien, Wittenberg, Germany, accessed on March 9, 2022, https://web.archive.org/web/20140215031210/http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/cranachs-wittenberg-altarpiece.html

Neil Macgregor in the book, seeing salvation: images of Christ in Art with Erika Langmuir, writes, “The altarpiece is, as Luther would have wished, the word made paint: and while every picture may tell a story, only a particular kind of picture can preach a sermon. The sermon here is on the Lutheran doctrine of salvation.” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 202.

[10] Binz, Transformed by God’s Word, 21-25.

Resources

Open Access – The Metropolitan Museum of Art (metmuseum.org)