Introduction

When looking at this picture of K-mart there may be many thoughts that may be running through your mind: you may be saying I remember when the store would have the blue light sales within the store, or I remember the good popcorn and ices they had, are there any more K-marts around now? But what in the world do K-mart and the black church doing prison ministry have in common? Sit back and let me share my story!

One of my favorite jobs that I had while in high school was working at K-Mart on Route 440 in my home of Jersey City, N.J. I enjoyed learning the business aspects of K-mart, and there was a time when I even thought about going into management with the company.

In the summer of 1991, after working overnight at K-Mart, I was walking home walk home when two cars of police officers (four plainclothes and two uniforms) pulled up, guns drawn. They commanded me to put my hands in the air. Their only explanation was this: “Oh, you fit the description of who we are looking for.” Fortunately, one of the officers shared that he knew me from K-mart and knew that I was not the suspect. What if he did not know me? What if, by chance, I had done something dumb because I was scared as hell? What if I were framed

implicating me in wrongdoing? I could have become part of the mass incarceration problem and without cause! Today, as I reflect on it, if that one officer did not know me and I made one wrong move, perhaps I could have been Eric Garner, Treyvon Martin, Walter Scott, or George Floyd. The situation and stories are real, and to this day I am haunted by that experience.

|

|

Problematizing Mass Incarceration: Racialized Social Control

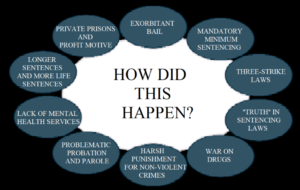

What about the men and women who are put into prison, some for crimes that they committed and others as a result of being accused? Mass incarceration is destroying families, leaving the home without a parent, and in many cases that parent is the male figure.

Obviously, the prisoner suffers as well: prison is damaging to mental health due to the consequent disconnection from family, society, and social support, loss of autonomy, diminished meaning and purpose of life, fear of victimization, increased boredom, the unpredictability of surroundings, overcrowding and punitiveness. Mass incarceration can also take away one’s worth and identity.

These negative impacts of mass incarceration disproportionally impact the black community. Lady Justice should not remove her blindfold to see if it is an African American man and give him more time, while his counterpart is given less time for the same crime committed!

Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow Mass Incarceration in Age of Colorblindness\(New York: The New Press, 2010) provides stark statistics to demonstrate these disparities. According to Alexander:

- 650,000 Americans return to their communities from prison each year. About half of them will return to prison within a few years.

- Nearly 50,000 legal restrictions against people with arrest and conviction records routinely block access to jobs, housing, and educational opportunities.

- Nearly 75% of formerly incarcerated people are still unemployed a year after release. A lack of stable employment increases the likelihood that an individual will return to jail or prison. Research has found that joblessness is the single most important predictor of recidivism.

- Black men have been admitted to prison on drug charges at rates 20 to 50 times those of white men.

- Prosecutors were found to pursue a mandatory minimum sentence for black people twice as often as for white people charged with the same offense.

- Black males receive sentences 19.1% longer than white males convicted of similar crimes.

- Black US citizens spend almost as much time in prison for a drug offense (57.2 months) as white citizens do for a violent offense (58.8 months).

|

|

|

What Role Can the Black Methodist Church Play

At this defining moment, the Black Church more so the black Methodist church needs to go where so many do not want to go to do meaningful and life-changing ministry. The days are over just sitting in a warm building waiting for the lost to come to us. No, No! This is the time for the Black Church to come out of its comfort zone of in-house programming. We must now leave the building and bring hope, forgiveness, and love to the least of these.

If the White church can make investments in Black inmates at mostly Black prisons across the state, then the Black Methodist Church must answer the call to do more. Their efforts may include adopting an inmate child while a parent is serving his time or visiting his elderly mother or father. In the state of South Carolina where I serve as a senior chaplain at the Lieber Correctional Institution each year for Christmas the Southern Baptist church of the State of South Carolina provides hygiene items for the entire South Carolina Department of Corrections. Could the church contribute more regularly?

The black Methodist church could also participate in the parole process. There are too many African Americans who languish in prisons today due to the inaction of a parole board. These boards possess an enormous amount of power in that they determine the length of sentence a person will serve, conditions of post-release, whether violations will result in revocation, and whether parole supervision can be terminated early due to compliance. But who are these people making such paramount decisions?

In many states, appointments to the local parole boards are the result of political favors, and often the decision-makers are not homegrown from the local community. They have little understanding of the neighborhood patterns, lifestyle traditions, or cultural norms that people bring with them into the hearing room. Without these connections, their assessments can be skewed and decisions can be unreasonable. I represented a woman who was being questioned by a hearing official about being a middle-school dropout. The hearing official asked her why she didn’t just get on the school bus. The woman spent several minutes explaining that no school bus ran in her neighborhood and described how her morning started with her waking up, finding her own breakfast, and getting to the metro without any parental supervision because her father was not around, and her mother worked the night shift. The disconnection was startling. Like each of us, board members have inherent biases and preconceived notions about the people who come before them.

In conclusion, the Black Church is obligated to minister to Black families. Especially black families impacted by mass incarceration. I will continue to call on black Methodist churches in particular to consider prison ministry as a part of their outreach. What change might we effect if black churches dedicated just a small part of their Evangelism funding nothing but prison ministry? As Dr. Martin Luther King said, “‘Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, what are you doing for others?’”

Reprinted with permission from Criminal Justice, Volume 36, Number 1, Spring 2021, at 6-12. © 2022 by the American Bar Association. All rights reserved. This information or any or portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

Roberts, J.Deotis. 1980. Roots of a Black Church: Family and Church. First edition. Edited by First edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Westminster Press. Accessed December Thursday, 2023.