In the chapter “Andy Warhol: The Producer as Author”, David James presented the trajectory of Andy Warhol’s career as he transitioned from being a significant figure in pop art culture to emerging as a notable and distinctive filmmaker in the realm of Avant-Garde cinema. James commenced by pointing out the iconic characteristics of Warhol’s films— “the simultaneous interrogation and exploitation of the media and the meditation on the elusiveness of the un-media-ted presence”—and tracing their origins back to his earlier paintings (James, 58). Warhol’s paintings represented a fusion of art and advertisement and could be even considered as “components of his own marketing strategies in the art business” (James, 59). Furthermore, Warhol constructed his works in a manner that was “virtually independent of a real human body or personality” as he often “reinscribed the artifice of the public image” (James, 60-61). At the same time, he opposed the conventional understanding and approach to grant authenticity to the artists.

With his eccentric but unique perspective of art and the fame and wealth he has garnered through his artistic endeavors, Warhol began his career as a filmmaker in the 1960s. James pointed out that “a general distinction between an early Warhol and a late Warhol can be elaborated in both formal and biographical terms” (James, 63). Warhol’s cinematic works progressively assimilated to the Hollywood cinema marked by the evolution of technological components towards greater sophistication, the transition from small-scale showcases to public exhibitions, and a shift in the films’ form toward a narrative-driven structure. “Two most polemically opposed modes of production of the time—the underground and the industry” got blended and further unified in Warhol’s films (James, 63). Inevitably, the discrepancy between his creations and the contemporary Avant-Garde films and “lacked any Brechtian engagement with the political functions of the mass media” aroused criticism from the underground (James, 66). In terms of dissecting Warhol’s films, James argued that “what distinguishes Warhol from his predecessors and successors is his disinterest in moral or narrative inflection”—he drew no boundaries between high art and street art, and the mainstream and underground (James, 67).

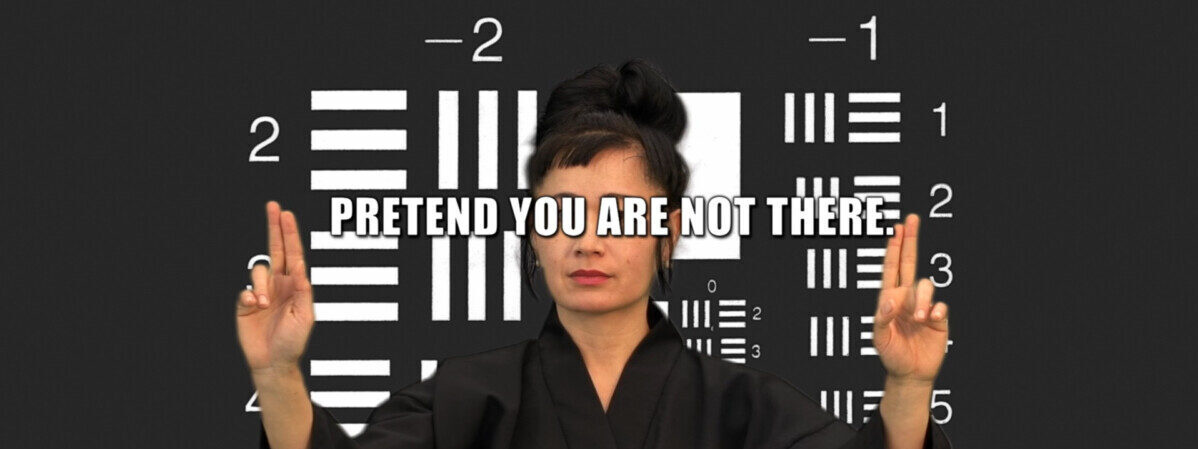

James then went on to delve into three major themes Warhol tried to address in his works—“an investigation of the process of being photographed and of being made the object of film; the construction and fragmentation of artificial selves by means of roles appropriated from film history or metaphorically related in some other way to Hollywood; the representation of exhibitionism and spectatorship in the narratives of feature films which themselves approach Hollywood’s formal and economic terrain” and analyzed how these themes manifested in various Warhol’s famous works such as The Chelsea Girls (1966, Warhol)(James, 68).

I perceive this article as an introductory, expository essay on Andy Warhol as James wrote in a relatively loose structure. The major takeaway for me is that different from lots of experimental filmmakers, Warhol didn’t resist mainstream art/cinema—in fact, he embraced the idea of commodity and popularity and often mingled them with his works. My questions arising from this article are: (1) James mentioned that Warhol began to delegate a substantial portion of responsibility to others in the production of some late films (James, 64). Wouldn’t this be in contrast with Camper’s idea that “an experimental film is created by one person, or occasionally a small group collectively” (Camper, 2)? What were some responses from the underground filmmaker community? (2) James described Warhol’s cinema as “his is thus a meta-cinema, an inquiry into the mechanisms of the inscription of the individual into the apparatus and into the way such inscription has been historically organized” (James, 68). How should we interpret the sentence?