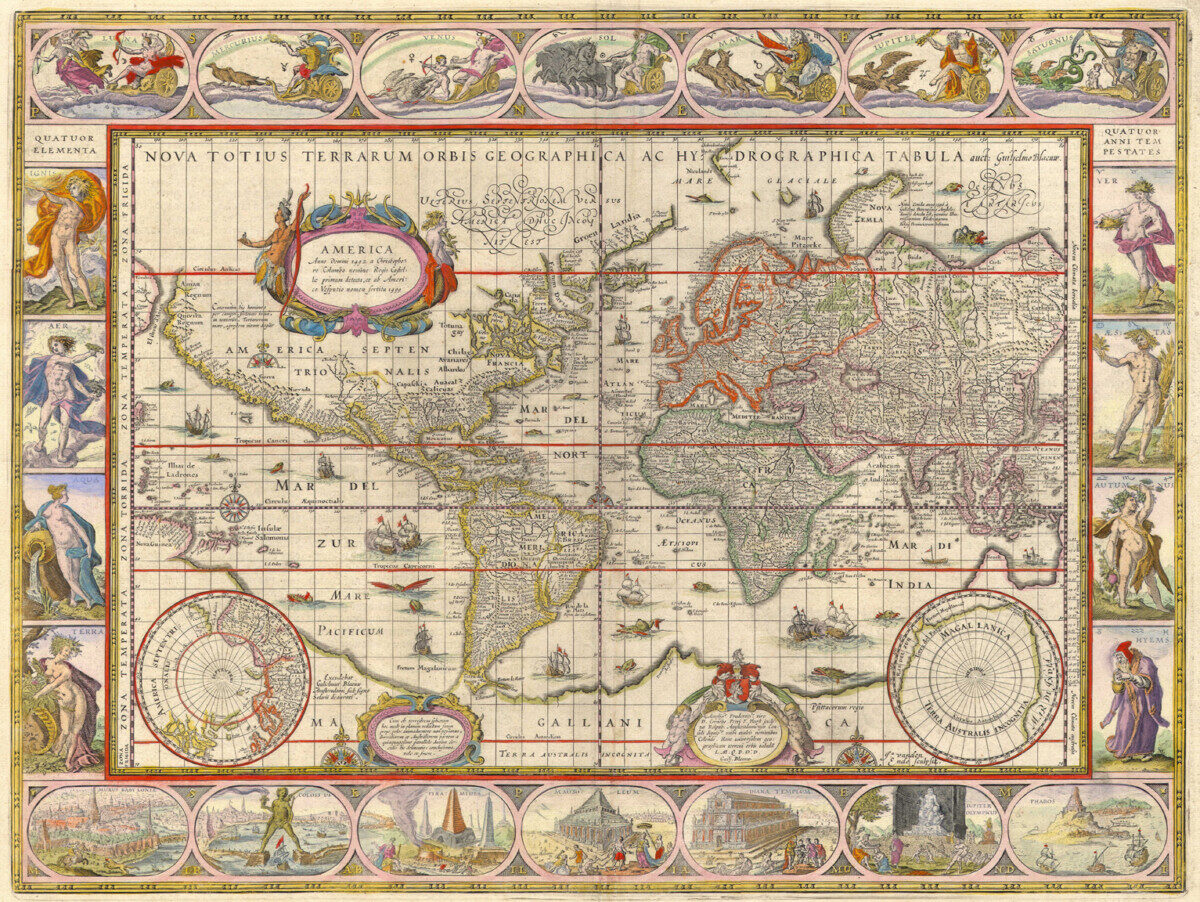

While I was unable to attend Claudia Swan’s lecture on Thursday, I was able to attend the graduate workshop on Friday morning. One thing that stuck out to me in the lecture was when she discussed the “call and response” pattern of map making in the Early Modern period. She brought this up when talking about the Waldseemuller world map from 1507. This was the first map to show America as a distinct and labelled continent. Swan talked baout how maps would be disseminated and people would respond with any new information that they knew about the world. With the new information, maps of the known world would be remade and redistributed, and the pattern would continue. This reminded me of Stephanie Porras’s discussion of Maerten de Vos’s St. Michael the Archangel going “viral” in the Early Modern period. I think both the maps and de Vos’s work highlight the communicative aspect of knowledge production. Where the maps were disseminated and altered when new knowledge arose, de Vos’s work served as a model for learning design principles in workshops. Porras also discussed how de Vos’s print was altered when copied by other artists. The process of creating a “copy” leaves room for differences, which is more clear in copies in different mediums or from different cultures. In both the Dutch maps and the copies of St. Michael the Archangel, we can see how the dissemination of these works are critical for knowledge production. However, the spread of these works also creates a conversation. Those who receive the print or maps imbed their own ideas into the works, which is then relayed back to the originating creator or location. These conversations are not unidirectional, but can incorporate the contributions from many individuals globally. While it may not seem surprising that a map would reflect the growing globalization in the Early Modern period, I think it is interesting that both the maps and prints highlight the “call and response” aspect of this interconnectedness.