Introduction

Baroque was widely recognized as a flourishing art style in Europe in the 17th century, but its impact on Asian artwork, especially Chinese ones, has been rarely discussed. Baroque architecture was introduced to China in the early 17th century, and gradually disappeared after the 1930s, leaving little traces in the form of a combination with either another European architectural style or a traditional Chinese one (Zhang). The process of the spread and variation of Baroque architecture in China can be divided into three stages considering its merger with traditional Chinese architecture to form the so-called “Chinese Baroque” and its efforts in reconciling several conflicts in the transition from traditional Chinese to modern architecture.

1. The spread and variation of Baroque architecture in China

1.1. Catholic churches in the late Ming Dynasty: Western Baroque architecture infiltrated

The introduction of Baroque architecture to China began when the Jesuits came to China to preach in the late Ming Dynasty (1600s) (Zhang). When looking at the internal changes in architectural styles, the Baroque architecture that emerged in Italy in the 17th century was the evolution of Michelangelo’s style in the most viral period of the Renaissance (Law). The external factors, however, are fueled by Catholicism (Law). As an important tool of Catholic belief, the Jesuits planned to infiltrate abroad after the Trent Council in the mid-16th century (Law). Its scope was not limited to Europe but also went deep into Asia and America (Law). In 1579, Italian Jesuit missionary Michael Ruggieri was sent to China for the first time to preach in Guangdong (Zhang). Since then, Catholic Jesuits have continued to come to China with Western merchant ships (Zhang). The spread of Catholicism in China was quite prosperous in the late Ming Dynasty, as many famous political figures, palace eunuchs, as well as Emperor Yongli and his empress all joined this religion (Zhang). At the end of the Ming Dynasty and the beginning of the Qing Dynasty (1640s), Catholic churches had been established in 13 provinces in China, with the most influential ones as the St. Paul’s Church in Macau (1602), Shanghai Jiading Catholic Church (1621), Wuchang Snake Mountain Catholic Church (1638), Beijing Xuanwumen Catholic Church (1650) and Fuyou Street Canchikou Catholic Church (1692), all of which have been destroyed except for the remnants of St. Paul’s Church, which is now named the Ruins of St. Paul’s Church (Zhu).

Judging from the appearance of the Ruins of St. Paul (Figure 1), it belongs to the early Baroque style as it imitates the Plan for the façade (Figure 2) by G. B. Vignola, which Baroque design was widely used to model Jesuit Churches. Accordingly, the Catholic Churches in China during the late Ming Dynasty, which corresponded to the 17th century when Italian Baroque architecture went viral, displayed a wide application of the Baroque style. Among the Baroque-style buildings all over the world, St. Paul’s Church in Macau is very representative. First of all, it has a dramatic rhythm in terms of its artistic expression. The front of the facade is grouped with double and three columns respectively, allowing the variation to create a sense of movement. The base and the eaves are broken but strengthen the connection between the upper and lower sides. The way the cravings on the wall are created produces a rich contrast of light and shadow, creating a sense of volume and drama. In addition, the deep niches on the wall, embedded bronze statues, patterns, plaques, and other carvings, have brought a unique artistic effect. The Ruins of St. Paul integrated architectural art, sculptures, and painting art into a whole, and pursued momentum and undulations in these three aspects, resulting in visual overlapping images and illusions. This makes the building symphonic and epic, the charm of which draws people in greatly.

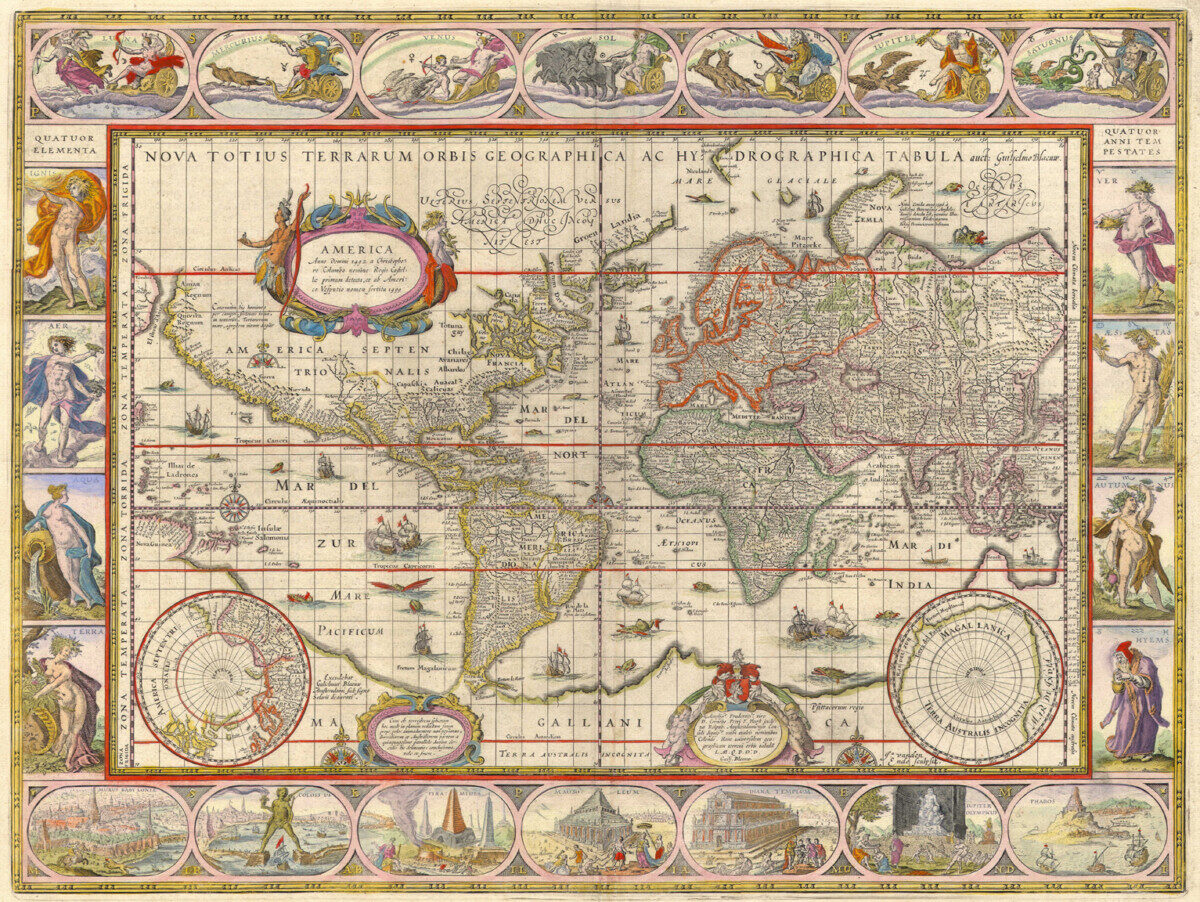

1.2. Western Building in Changchun Garden: The Origin of Chinese Baroque

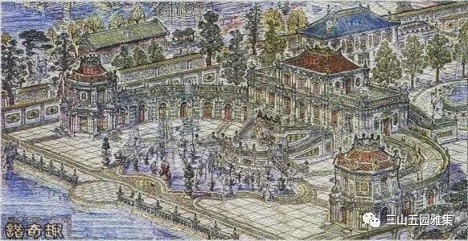

From the early to the middle of the Qing Dynasty (1700s), the spread of Catholicism was restricted by the Qing court (Zhang). However, the Qing court appointed some Western missionaries as officials to participate in the creation process of several artworks which have been known for their unique combinations of Chinese and Western style, including four of the most impressive writings by Emperor Kangxi (Zhang). It was under this historical background that, from 1747 to 1760, inspired by Western paintings, Emperor Qianlong ordered Italian missionary G. Castiglione (1688-1766), French missionary Zhicheng Wang (J. D. Attitet, 1702-1768), and Youren Jiang (P. M. Benoist, 1715~1774) to design and supervise the construction of the Western Building of Changchun Garden (Figure 3) (Chen).

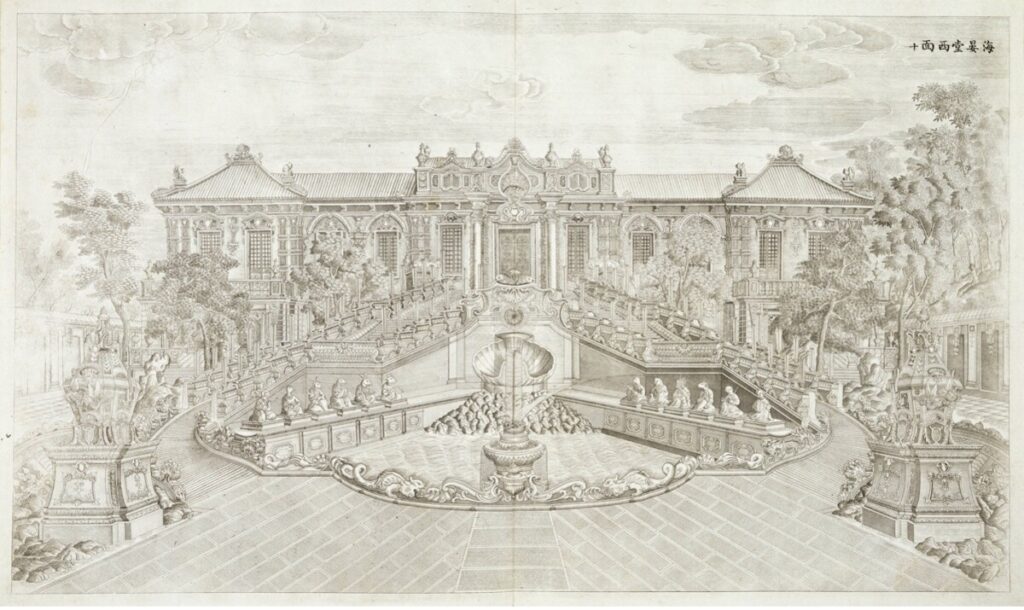

The Western Building absorbed the layout of a Baroque Western garden and architectural style while using Chinese craftsmen, materials, and techniques during construction and following the will of the Chinese emperor and the regulations from court etiquette, such that the European Baroque blended into the details and characteristics of Chinese architectures (Chen). For example, the “Xieqiqu-Shuifatai-Huanghuazhen” scene (Figure 4) uses the layout of the Baroque courtyard, blending the architecture, the garden, the waterscapes, and the sculptures together to add a sense of dynamics to the building group and the external space. But on the other hand, the sense of order and playfulness can still be found in the hierarchical Chinese-style roofs, the high white marble platform where the main building is placed, the divided courtyards by walls, and the square pavilion at the exit (Chen). In another example, the “Yuanyingguan-Dashuifa-Guanshuifa” section (Figure 5), the architectures and the layout are very similar to the Baroque style with a semi-circular porch on the front facade and a triangular gable above the porch, supported by two stone pillars on both sides. This design is a common technique in the Baroque style, adding solemnity and majesty to the architecture (Chen). However, there are still traces of traditional Chinese details such as sculptures made of pure-white marble and roofs made of five-color glazed tiles, leading to a different sense of order than Baroque. The center of the garden is the throne on the platform of “Guanshuifa” (Figure 6), surrounded by a semicircular stone screen as a shelter at its back, multiple water views in the front, and a temple at the distance. This change of layout solidified the flowing space of Baroque and lost the civic quality of the Western square (Zhu).

In the mid-Qing Dynasty, the Western Building in Changchun Garden was the first architecture that incorporated the Western Baroque style, while merging with the complicated and detailed decorations of traditional Chinese architecture (Steinhardt). Surprisingly, the native materials and existing construction techniques made it easy for Chinese people to imitate, promoting the Western Building in Changchun Garden to be a prototype for many “Chinese Baroque” architectures over the next century (Zhu).

1.3. Eclectic Baroque: The Transmutation of the Baroque

Around 1910, the eclectic Baroque style successively appeared in Shanghai, Guangzhou, Harbin, Wuhan, and other big cities (Chen). One of the basic characteristics of eclectic Baroque is that the appearance of these architectures is a combination of various eclectic styles but also adds Baroque to different degrees. In addition, they mostly show up as larger commercial buildings and banks with structures of modern materials and are mostly designed by well-trained architects instead of civil craftsmen (Zhu).

Built in 1917, the Shanghai Xianshi Company Building (Figure 7) combines detailed and delicately curved ornaments in the Baroque style and traditional Chinese materials (Chen). Its hollowed-out “Moxing Tower” mimicked the two side towers in Sant’Agnese in Agone (Figure 8) by F. Borromini (1599~1667). The “Moxing Tower” takes in the form of the belfry of the original version, with the Corinthian columns and the hollowed-out center (Colonnese). They both function to serve the clock that is in the center bottom of the tower (Chen). Instead of a two-layer tower like the Sant’Agnese in Agone Church, the Chinese craftsmen decided to add one more layer, the reason behind which is still unknown (Colonnese).

The hollowed-out tower on top of the main building is common in Chinese Baroque commercial buildings during the eclectic period. These kinds of towers originated from the bell towers on the Sant’Agnese in Agone and originally appeared in pairs, although most of the commercial and entertainment buildings in China take the form of a single tower. This is because, in addition to being unconventional and highlighting the facade in order to attract business, the tower is mainly used for Fengshui, which is a traditional custom in China to change the fate of individuals and businesses by virtue of the location of buildings, the direction of sitting, and the relationship with the surrounding like mountains and water (Zhu). In this way, the idea of the original Western bell tower was retranslated into the Chinese Fengshui tower.

Throughout the development of Chinese eclectic Baroque, the elements of irrational Baroque are gradually decreasing, while the elements of classicism and rationality are rising. Comparing the architectures built in the early 20th century and the ones later, the Baroque practice is restricted to parts while the overall presents a concise and classic style. The evolution to eclectic Baroque heralds the end of Chinese Baroque.

2. The role of Baroque in the modern transformation of Chinese architecture

Since the Chinese government opened the treaty ports, a large number of Western buildings have poured into China, which were no longer limited to churches but have been extended to consulates, foreign firms, banks, bureaus of the Ministry of Industry, clubs, shopping malls, hospitals, and schools, etc (Steinhardt). Some of these buildings are in Baroque style, but Romanesque, Byzantine, Gothic, and cultural Renaissance, classicism, eclectic, colonial, and even Art Nouveau style appeared almost simultaneously (Meng). The introduction of Baroque to China coincided with the transition of Chinese architecture from traditional to modern, which Baroque participated in the whole process (Zhu). In contrast, Romanesque and Gothic styles of art, which were introduced at the same time as Baroque, had almost no impact on Chinese architecture, except occasionally in churches (Bailey). The choice and acceptance of the Baroque style by Chinese architects and artists during the modern transformation of architecture leave questions behind (Zhu). From the perspective of the external environment, the widespread Baroque in China thanks to the tenacious cultural penetration of Jesuit missionaries (Law). Emperor Qianlong’s imperial designation of the Western Building in Changchun Garden objectively played a preconceived and exemplary role (Zhang). However, the decisive factor still comes from the inherent attributes of the Baroque.

First of all, the Baroque came into being when the feudal system in Western Europe was falling apart and the Catholic theocracy was facing a life-and-death challenge (Zhu). These historical backgrounds encouraged this hence-born style to imply the restlessness of the turbulent era, which corresponded to the sentiment of the local domestic mainstream cultural consciousness in China at the time (Zhu). The failure of the two Opium Wars triggered the collapse of the traditional cultural value system. In the midst of loss, Chinese people eagerly seek support from Western culture through Westernization movements (Zhu). These revolutionaries and their followers took Baroque as a symbol of improvement due to its behind meaning and resemblance in their emotions.

In addition, the conflicts between the traditional and modern Chinese architectures mostly existed in the structures, materials, and techniques, which the Baroque style is quite flexible in (Zhu). It allows the Chinese craftsmen to use familiar materials and structures, including both traditional bricks, woods, and stones and modern reinforced concrete elements while adapting to this new style. In this way, Baroque alleviated the contradiction in the process of the modern transformation of Chinese architecture.

What is more, Baroque architectural forms are very inclusive. In fact, similar to that the Baroque was introduced from Italy to other European and American countries with many variations, another Baroque variant emerges when it came to China. For example, the Italian scholar Conti believes that “every independent work of Baroque creates its own balance among these many characteristics, and each country develops these elements in different ways. A deep understanding of the differences between each region and the nation is the basis for a correct understanding of the overall picture of Baroque art” (Zhu). As the Chinese architects worked to incorporate Baroque into traditional Chinese buildings, they make reasonable changes to the original Baroque in order to create an image of the same style or convey messages that are suitable for the local cultural and historical background.

Lastly, there are some ideological coincidences between Baroque and traditional Chinese architectures (Chen). Baroque pursues movement and momentum, while traditional Chinese architecture has always incorporated flexible and movable images such as recurved eaves and raised corners (Chen). Different from the rational composition method of Western classicism, Baroque resorted to intuition, senses, and imagination, which are related to the stressed importance of sensory effects in traditional Chinese architecture (Chen). The Baroque employs curves that are in line with the aesthetic taste of Chinese classical architecture, and Chinese craftsmen have had experiences in dealing with a whole set of curves such as cornice warping, curling, and so on (Zhang). Baroque and traditional Chinese styles both emphasize decorations so that Chinese architects could easily misunderstand the concave-convex carvings in Baroque as variations of Chinese traditional beams and frames (Chen). In short, to a certain extent, Baroque architecture adapts to the changing mental state of the Chinese people and coincides with traditional architecture for a smoother transition for Chinese architecture. In particular, Chinese craftsmen are able to convert certain Baroque terms into traditional architectural discourse with ease, which may be why Chinese Baroque shows considerable creativity. Baroque reconciled several contradictions and conflicts in the transformation process of modern Chinese architecture, resulting in widespread development in China that could have been foreseen.

3. Characteristics of Chinese Baroque

3.1. Incorporate traditional Chinese architectural details.

Similarities exist in the complicated carvings in Baroque and the rich decoration details of traditional Chinese buildings. This allows Chinese craftsmen to easily incorporate traditional architectural details into Baroque. A typical example is the gate of the Beijing Agricultural Experimental Site (Figure 9), which includes traditional architectural cloud patterns and wandering dragons in the Baroque gate. It is representative of new Chinese Baroque shops at the beginning of the last century by infiltrating Chinese-style plaques, pot doors, pictures of pine and cranes, and decorative patterns of lotus and peony flowers into the Baroque façade (Chen). Some other architectures also contain the practice of embedding traditional leaky windows into the Baroque façade, showing considerable creativity (Chen).

3.2. Diversified traditional materials and techniques

Another feature of the Chinese Baroque is the abundance of traditional materials and crafting methods. Glazed tiles and white marble carvings are the quintessence of traditional Chinese architectural decoration, which can be traced back to the Western Building in Changchun Garden (Zhu). Similarly, glazed tiles are not only used for the ceiling in the Wuhan University Gymnasium (Figure 10), but also for the decorative eaves of its Baroque Gable, becoming an important means of compositing a baroque element (Chen). The Liu’s Manor in Dayi County, Sichuan Province (Figure 11), where the Baroque gatehouse is beautifully decorated with colorful clay sculptures, should be another excellent example of incorporating Chinese factors into Baroque.

However, it is worth noting that the original Baroque and Chinese Baroque differs significantly when it comes to bricks. According to Japanese scholar Yasuhiko Nishizawa, Western architecture is usually covered by mortar, cement, or imitated stones to cover the original brick structure because the exposure of bricks is not an appreciated look by Western people (Zhu). Nevertheless, Chinese Baroque architectures usually leave the brick structures as they are because Chinese people have a different opinion about bricks, possibly due to the familiarity with traditional hand-built houses that bricks evoke (Zhu).

3.3. Interpretation of the Chinese meaning of Baroque terms

It is a classic Baroque architectural practice to add concave-convex cravings to the flat square columns, but this was misinterpreted by the Chinese craftsmen as an intentional imitation of the wood structure, which was integrated with the traditional Chinese architectural gatehouse (Zhu). Thus, it became one of the most common forms of Chinese Baroque facades, which is shown in one of the most classic examples, The Liu’s Manor in Dayi (Figure 11). The typical Chinese gatehouse is composed of the upper part of the “building” and the lower part of the “fake-wood framework” structure. Traditionally, “buildings” are often made into cornices, which seem out of fashion and are replaced by Baroque curves and other similar styles with the variation of modern cultural values (Zhu). On the other hand, the lower part still retains the form of imitating wooden trusses, called “three rooms and four pillars” (Chen). Therefore, although the façade has a Baroque sense of convex and concave sculpture, it is different from the arbitrary use of columns that often exists in Western Baroque architecture.

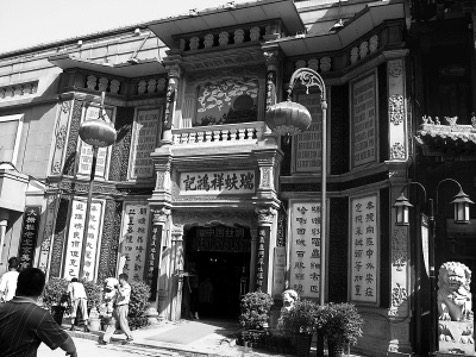

3.4. Usage of plaques and couplets to express ideas

Different from Western architectures, Baroque included, which is good at conveying certain meanings simply with shapes and cravings, traditional Chinese buildings generally do not have expressive functions by themselves. It is unique that Chinese architects chose to express opinions through add-ons like plaques and couplets (Meng). This characteristic is also adapted to Chinese Baroque and eclectic Baroque (Meng). In fact, as early as when the Jesuit missionaries built Baroque churches in China in the 17th century, they had followed such practice of traditional architecture (Bailey). Since then, this usage has become more common in the Baroque facades of some Chinese gatehouses.

Conclusion

Baroque stood out from other imported artistic styles in China due to its evocation of a matched emotion, its inclusiveness in the construction process, and its accidental similarity with the original Chinese style. These allowed Chinese people to adopt it during their transformation of architecture, which includes Catholic Churches as a pure mimic of the original Baroque, Chinese Baroque where Chinese understanding and elements are added, and the eclectic Baroque nowadays that contains little Baroque when suitable.

A more detailed introduction that focuses on the architectures mentioned above can be found here.

Bibliography

Bailey, Gauvin A. Art on the Jesuit Missions in Asia and Latin America, 1542-1773. University of Toronto Press, 1999.

Chen, Xiuzhen. 巴洛克建筑在中国的发展 [The development of Baroque Architectures in China]. Guangzhou Architectural Materials, 2010.

Colonnese, Fabio. Perspective, Illuysion and Devotion. The Chapel of S. Agnese in Sant’Agnese in Agone. academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/25829377/2016_Perspective_Illusion_and_Devotion_The_Chapel_of_S_Agnese_in_Sant_Agnese_in_Agone, 2016.

Law, Gail. Chinese Churches Handbook. Chinese Coordination Centre of World Evangelism, 1982.

Meng, Fanwei. 我国新巴洛克建筑的保护与探析 [The Protection and Investigative Analysis of the New Baroque Architectures in China]. cnki.com.cn, https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-GYJZ202106057.htm, 1921.

Ross, Andrew C. Vision Betrayed: The Jesuits in Japan and China 1542-1742. Orbis, 2003.

Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. Chinese Architecture: A History. Princeton University Press, 2019. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77f7s. Accessed 24 Apr. 2023.

Zhang, Fuhe. 中国基督教堂建筑初探 [Initial Investigation of Chinese Christian Churches]. Huazhong Architecture Magazine, 1988.

Zhu, Yongchun. 巴洛克对中国近代建筑的影响 [Baroque on Chinese Modern Architectures]. China Academic Journal Electronic Publishing, 2000.

Image References

Figure 1: The Ruins of St. Paul

Figure 3: One restoration image of the Western Building of Changchun Garden

Figure 4: Painted Restoration of “Xieqiqu” of Changchun Garden

Figure 5: Animated Restoration of “Yuanyingguan” of Changchun Garden

Figure 6: Painted Restoration of “Guanshuifa” of Changchun Garden

Figure 7: Shanghai Xianshi Company Building

Figure 8: Sant’ Agnese in Agone

Figure 9: Beijing Agricultural Experimental Site