Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio is arguably one of the most famous and influential figures in Europe during the Baroque period. Living a short life of 38 years, Caravaggio nonetheless leaves us with a wealth of works worth contemplating. His naturalistic depiction of figures and dramatic use of light and dark come to define European Baroque art and later influence a school of artists that proudly call themselves “Caravaggisti.” Although Caravaggio is considered as a pioneer in artistic styles, a close examination of his paintings reveals his profound interest in Renaissance art and his conversation, if not rivalry, with some of the greatest Renaissance artists, including Michelangelo and Raphael.

At the beginning of his artistic career, Caravaggio devotes himself to secular works. The series of paintings by Caravaggio from 1592 to 1600 experiments with compositions of one or a few figures, usually in simple settings without much ornamentation. The half-length format that Caravaggio prefers during this period implies portraiture in antiquity and in the Renaissance, which indicates the artist’s consciousness to artistic traditions from the beginning of his career.[1]

Boy with Basket of Fruit (Figure 1) and A Concert of Youths (Figure 2) demonstrates the young painter’s interests and ambitions. Although Boy with Basket of Fruit can be classified as a portraiture, the meticulous depiction of the fruit at the center of the work is prominent and leans the painting towards a work of still life. The grapes are fresh with dews, and the pears and apples appear so realistic as if they were just harvested from the trees. The artistic enthusiasm towards still life can be traced back to antiquity, as Pliny the Elder and other authors describes still life paintings in their writings; Renaissance artists later revive such interest as they attempt to imagine lost ancient artworks through literal records.[2] Caravaggio is certainly fascinated by the tradition at the early stage of his career, although his passion does not last long.

In A Concert of Youths, Caravaggio continues his exploration of the half-length format, yet this time he studies the multi-figure composition. The artist presses four young musician into a shallow, unidentifiable space, and they are in preparation of a musical party. The angel-like allegorical figure on the top left corner holds two strings of green and purple grapes, the careful depiction alluding to his continuous interest in still life. The figure who is reading the score sits on a table on the foreground of the painting, separating the poetic and sacred world inside and the reality to which we belong. The painting rivals with its Renaissance predecessors, such as The Parnassus by Raphael, where a mythological land that is filled with antiquity fantasies is constructed. Yet, Caravaggio is not completely successful in this endeavor, as the figures look disconcertingly contemporary.[4] Nonetheless, it is obvious that the artist has the great Renaissance artists in his mind that he is going to compete with throughout his career.

At such an early time, Caravaggio is yet to form his distinctive style that somewhat defines European Baroque paintings. However, we can still pull out a few developing characteristics from the artist’s secular works. For example, he uses an ambiguous background that does not suggest a particular place almost from the beginning of his career, as exemplified by both works shown here. A specific source of light from the top left corner of the painting is also employed in Boy, a personal favorite of Caravaggio, although at a much warmer scale.

It was not long before Caravaggio begins painting religious subjects, and he continues to create religious works for the majority of his life. He respects and follows many Renaissance pictorial traditions, yet he also defines his own style through his enthusiasm towards naturalism and strong elicit of emotions.

The Supper at Emmaus (Figure 3) is one of Caravaggio’s early religious works, depicting the moment when Christ reveals his identity to two disciples who invite him for dinner. The painting is again set in a mysterious brown background, and a warm, soft source of light sheds onto the scene from the top left corner. At the center of the painting is a table full of lively fruit, chicken, and bread; the artist is still much interested in still life at this point, but the painting is one of the last works he engages with the topic.[6] Unlike Concert where the table is placed in the foreground, one of the disciples sits between our world and the pictorial world. As he just begins to stand at the awe of Christ’s presence, the audience could feel as if the disciple’s arms are about to intrude into the reality, which blends, instead of separating, the boundary of the two spaces.

Christ sits at the center of the table, his right hand reaching out to bless. Overall, the gestures of the figures, including the extending arms of the disciple on the right, are rather dramatic and indicate the artist’s recent study of Renaissance masters. Raphael’s works and Leonardo’s Last Supper in Milan may be the sources of his interest, and Leon Battista Alberti also states that “interior thought and feeling must be depicted in art through outward gesture,” and “the movements of the body reflect those of the soul.”[7]

Caravaggio’s study of the old masters does not indicate blind following of them. Indeed, he explicitly and implicitly rejects Renaissance idealism through the close study of still life and a focus on models.[9] If we have to classify the artist, Caravaggio revives from mannerism prevalent in the late Renaissance and embraces naturalism. His innovation partly goes hand in hand with the Church Reformation during that time, where the stir of emotions and the focus on educational visualization of the episodes in the Gospels are advocated and emphasized by reformers such as Ignatius of Loyola and Filipo Neri.[10] Caravaggio’s style divides Renaissance and Baroque art, while remaining in conversation with what has come before.

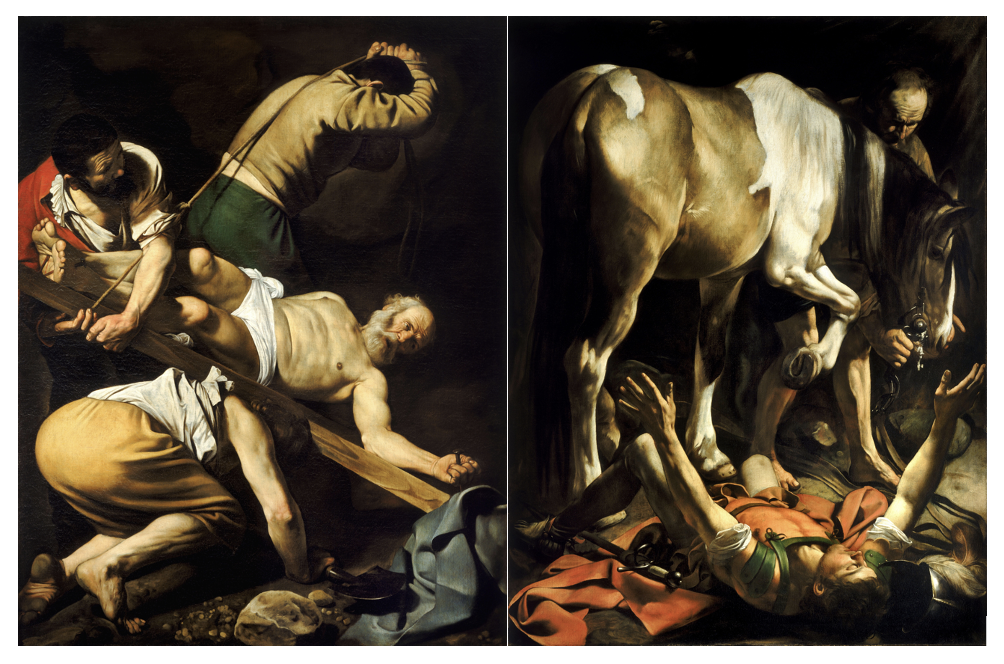

Caravaggio gained his fame after 1600 and received several commissions for large-scale paintings, where he matures his style. A representative work of the fully grown artist is the Cerasi Chapel where he paints two side paintings (Figure 4).

Both paintings crowd the figures into an uncomfortably narrow space that is unidentifiable given the completely black background. The works are illuminated exclusively by harsh light from the top left corners, the contrast between light and dark dramatic. The confrontation is further elevated by the strong diagonals; the cross of St. Peter and the two sweaty workers raising him up almost form an “X” at the center. Caravaggio employs all the visual devices to create a set of works that are shocking, if not overwhelming, upon encounter. The two paintings themselves also form an interesting juxtaposition: whereas The Conversion of St. Paul is intimate and still, The Crucifixion of St. Peter is violent and physical.

The set of paintings is obviously radical and abrupt for viewers expecting Renaissance-like works, and Caravaggio has thereby established his dramatic, yet naturalistic, style that he continues to work with for the rest of his career. However, despite its innovation, the Cerasi Chapel set is not without Renaissance prototypes. Michelangelo has created the same themes of the conversion of St. Paul and the crucifixion of St. Peter as the side paintings for the Pauline Chapel.[12] Caravaggio is definitely aware of the predecessor’s work because he shows St. Peter in the process of being lifted, a distinctive innovation by Michelangelo. The inclusion of a horse in The Conversion of St. Paul is another Renaissance tradition that the artist chooses to follow.[13] Nonetheless, whereas Michelangelo prefers a landscape setting with many figures, Caravaggio focuses on the saints in a cramped place. Through his naturalistic yet psychological works, the Baroque artist sets himself apart from the Renaissance predecessor on the same theme.

Caravaggio died at the age of 39 with relatively little notice despite his fame.[14] Although he never has a studio, his followers, referred to as the Caravaggisti, are abundant. Most of the followers, however, are more interested in studying the master’s style, so the strong connection to Renaissance artworks is lost along the way.

Death Comes to the Table (Figure 5) is created by a mysterious Flemish painter Jean Ducamps that we know little about; he is a founding member of the society of Netherlandish painters in Rome, and records show that he forms a Netherlandish workshop with at least three apprentices.[15] Ducamps sets the scene in a Caravaggesque dark background with light from the top left corner. Further, the memento mori painting is reminiscent of The Supper, in that both works have the same composition of centering a table with figures in the foreground. The lively depiction of the food, especially two strings of green and purple grapes, pays attribute to Caravaggio. Overall, the painting captures the artist’s distinctive composition and his early enthusiasm in still life. However, unlike Caravaggio who prefers dressing his figures in antique clothing, the setting of Death is modern, and the tone of the figures’ clothes is light and bright, which alludes to Ducamps’ Flemish training.

A closer follower of Caravaggio is Rutilio Manetti, and The Chastisement of Cupid (Figure 6) demonstrates his careful study of the artist. The familiar black, shallow space and light from the top left corner set the scene for the painting, the contrast between light and dark clear. Indeed, The Chastisement is almost a summary of Caravaggio’s works in the Cerasi Chapel: Manetti incorporates the violence and movement in St. Peter to Mars, while the extreme foreshortening of Cupid and his stillness remind the viewers of St. Paul. Stylistically, Manetti masters Caravaggio’s skills and characters, yet he is not much interested in Renaissance art; one of Caravaggio’s greatest features, unfortunately, is lost in the later Caravaggesque works.

The Cupid theme of The Chastisement may remind one of Caravaggio’s Amor Vincit Omnia. While Caravaggio’s Cupid stands in triumph of the highest human endeavors represented by various instruments, including a violin and a chisel, the Cupid in The Chastisement is about to be beaten, his arrows broken. There are not many symbols in Manetti’s work, except an amor that represents Mars who kills and destroys.[17] The reason behind the opposing portrayal of Cupid, the embodiment of love, is worth investigating, and it is interesting to see how the Caravaggisti contrasts with the master nonetheless.

Only when we look before and after Caravaggio can we truly understand the master of the European Baroque art. He is a bridge that connects to Renaissance art, and his distinctive dramatic, psychologic naturalism has influenced generations of artists after him.

P.S. An accompanying online exhibition of the essay can be found here. Please turn on audio for the guided tour for the best experience.

[1] Howard Hibbard, Caravaggio (New York: Harper & Row, 1983), 25.

[2] Hibbard, 18.

[3] “Boy with a Basket of Fruit,” Wikipedia, Wikipedia, accessed April 23, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boy_with_a_Basket_of_Fruit.

[4] Hibbard, 35.

[5] “The Musicians (Caravaggio),” Wikipedia, Wikipedia, accessed April 23, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Musicians_(Caravaggio).

[6] Hibbard, 75.

[7] Hibbard, 77.

[8] “Supper at Emmaus (Caravaggio, London),” Wikipedia, Wikipedia, accessed April 23, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supper_at_Emmaus_(Caravaggio,_London).

[9] Hibbard, 80-85.

[10] John Gash, “Counter-Reformation Countenances: Catholic Art and Attitude from Caravaggio to Rubens,” An Irish Quarterly Review 104, no. 416 (2015): 377-81.

[11] “Cerasi Chapel,” Wikipedia, Wikipedia, accessed April 23, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cerasi_Chapel.

[12] Stephen J. Campbell and Michael W. Cole, Italian Renaissance Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 2017), 509-11.

[13] Hibbard, 126-28.

[14] Richard E. Spear, Caravaggio and His Followers (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), 15.

[15] Erin Downey, “Learning in Netherlandish Workshops in Seventeenth-Century Rome,” Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 68 (2019): 355.

[16] “Object Lesson: Death Comes to the Banquet Table by Giovanni Martinelli,” New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans Museum of Art, accessed April 23, 2023, https://noma.org/object-lesson-death-comes-to-the-banquet-table-by-giovanni-martinelli/.

[17] Mina Gregori, Luigi Salerno, and Richard E. Spear, The Age of Caravaggio (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985), 277.

[18] “Cupid Chastised,” Art Institute of Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, accessed April 23, 2023, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/59847/cupid-chastised.