Before I came to Berlin many people described the city as a place where “no one even speaks German anymore. They all speak English.” While this has proven a gross exaggeration and German is still the most frequently used language both in speech and writing, there is a grain of truth to this assertion. Both spoken and written English are often used, and while in some areas of the city the primary purpose of this is to make them more accessible to tourists, in others it is to facilitate communication between people of different linguistic backgrounds, one or both of which is not German.

Like other major European cities, Berlin is a major tourist destination, and it therefore makes sense to have a certain amount of information available in English. For example, this sign for the Berlin Zoo is written in both German and English, because those who operate it wish to market it to both locals and tourists. The same is true for other tourist-heavy parts of the city, such as the area around the Brandenburg Gate. English is also heavily spoken in these areas, as restaurant owners and street vendors attempt to coax tourists into buying their products.

However, English is also commonly seen and heard in parts of the city far from the tourist centers. For example, I observed this sign at the U-Bahn (metro) station that I use to get to work, which is well south of the city center and its many attractions. The reason for this dates back to the period following World War II when Germany recruited Gastarbeiter (“guest workers”) to fill their labor shortage. These workers came primarily from Turkey, but a large number from Southern Europe came as well. However, much to the dismay of many Germans, these “guest workers” decided to stay permanently and make new lives in Germany.

Over time the immigrant community in Berlin has only grown larger and more diverse. However, with more and more immigrants from all around the world the issue of finding a common language becomes more difficult. Many more people learn English as a second language than German, and for this reason it is often more expedient to communicate in English, hence why signs can be found in both English and German in any part of the city. Thus, like the situation Leeman and Modan discuss, the the primary audience of these signs is not native English speakers, although in this case those reading them do understand English.

This diverse immigrant community means that one hears a variety of languages on the street. Just in one trip to the grocery store or the gym I will often here German, English, Turkish, Spanish, Italian, and Russian. However, this linguistic diversity often does not extend to written language, apart from in very small pockets of the city. It would be too difficult to label signs in every one of the many languages commonly heard in Berlin, so the authorities settled on English, the most likely language to be known by a given person besides German. This frequent use of English also creates a strange phenomenon wherein one will here two non-native English speakers speaking in English because that is the one language they have in common.

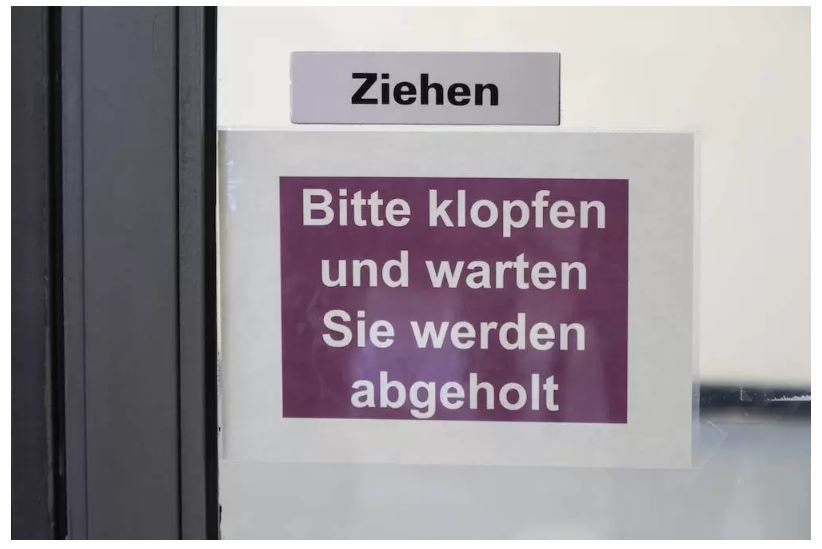

Interestingly, my experiences on the streets and in private businesses have contrasted greatly with my experiences dealing with government entities. Since I am participating in two study abroad programs, I have had to go through the process of applying for residency, and in my experience everything pertaining to this process has been conducted in German. Forms and signs in pertinent buildings, such as the one below, are in German only. Appointments also take place in German only. I found this paradoxical, especially in the Ausländerbehörde (Foreigners’ Office), whose purpose is dealing with foreigners, most of whom don’t speak German. My interpretation of this phenomenon is that the city government is worried people can get by without ever learning German, and wants to force them to learn so that English does not supplant German. This contrasts with the situation in the Leeman and Modan article, because the growth of English signage seems to have occurred despite the city government rather than because of it.

While English is used to make the city more convenient for tourists, its primary function is actually to facilitate communication between full-time residents of a diverse linguistic background. When I was told of the prevalence of English in Berlin, I expected people were referring to the baseline level of tourist English that can be found in most Western European cities. However, I have since realized that that is not the case. With people coming to Berlin from all over the world, English has become Berlin’s lingua franca.

I think it’s really interesting that you brought up how English is used as a baseline for people belonging to countries where English is used as a secondary language. Whenever I’ve seen or heard about things like signs or menus being written in English in European countries, I always assumed that it was because of the tourism industry rather than a language commonality among “foreign” nations. I think it’s actually kind of amazing that English, a language I’ve taken for granted as a native speaker, can be used to unite people from so many different cultural backgrounds.