Makoto Shinkai’s Suzume is a road movie (?) with a heavy ritual influence. The teenager, Suzume, crosses Japan shutting supernatural “doors” that leak catastrophe into the present time. Each site she went to is a ruin, either school, bathroom, or amusement park. Those are places that everyday life was interrupted. By making Suzume kneel, touch the ground, and speak different names, the film literalize the act of remembrance as a public act rather than a private feeling. It makes Suzume a symbol of memory.

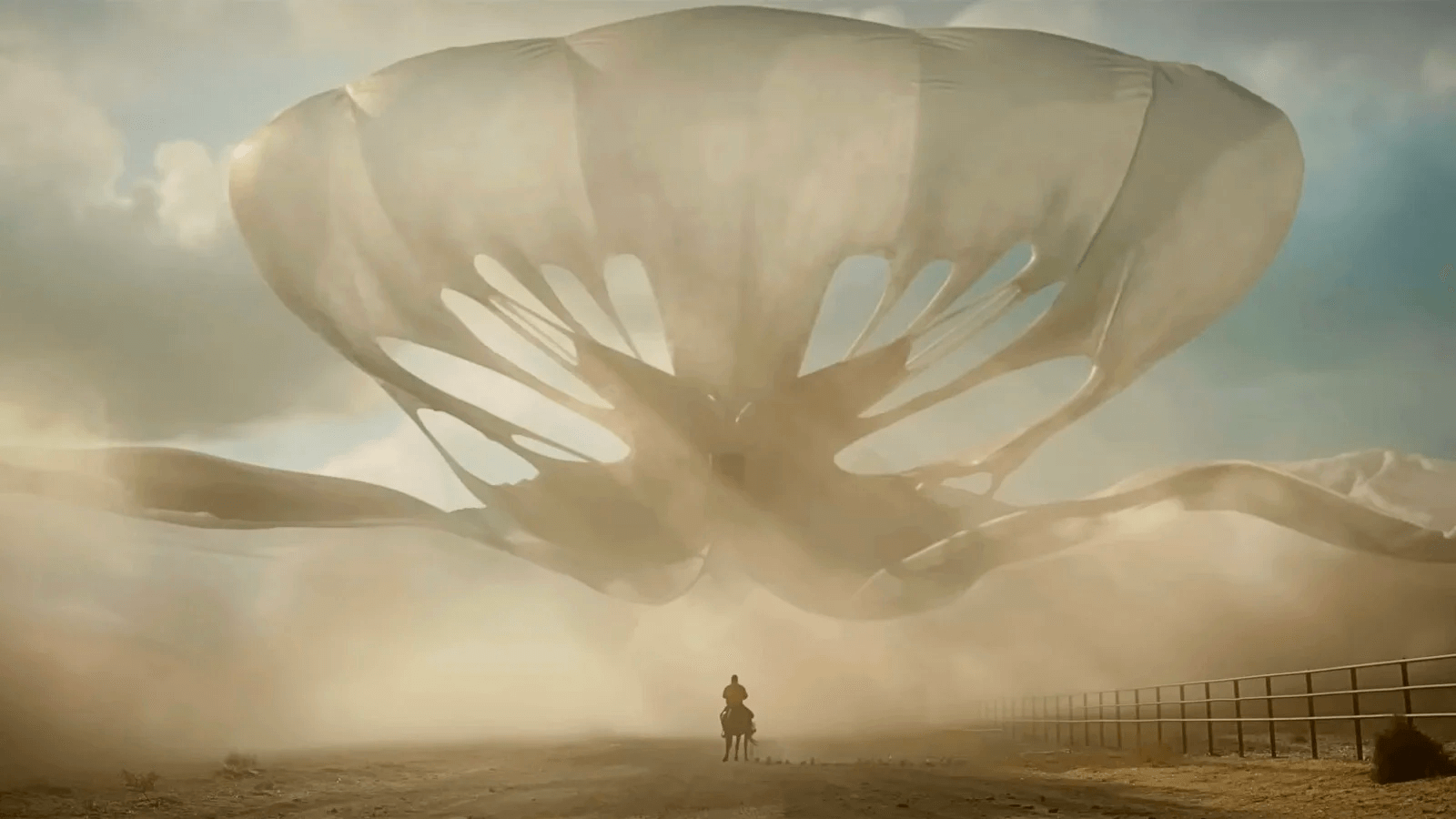

Visually, Shinkai used this through recurring motifs: doors framed against the sky, also with short passages like operate like associational form inside a classical narrative.

The character arc threads cleanly through the travel experience of Suzume. She begins her story as someone running: running late to school, and running late to process a childhood loss. Each stop she made pairs with a temporary caretaker and a “door” that must be closed. This story formation makes the help and repair intertwined. Sota’s transformation into a three-legged chair looks like a joke, but it is a symbol that shifts the theme from romantic into burden and compassion. Suzume must carry responsibility rather than be carried by an adult character. Daijin, the cat-like god, complicates things further: it wants love and attention, but also demands duty. That tension—affection versus obligation—maps onto Suzume’s choice to grow up.

Technically, Suzume is a hybrid of hand-drawn and computer digital compositing. We can see its hand-drawn characters, but as well as the sky, water, fog, and all the background effect being computer generated. Shinkai also uses pockets of limited animation: held poses and micro-movements to stage stillness against richly rendered environments. Those holds let music and ambient sound carry emotion while the image rests, so when motion returns to the main component of the shot, it hits with force.

Sound is also important in Suzume. Big moments often land on a sudden hush—right before a key turns or a “door” seals. That drop creates negative space so the next sound (a thud, a breath) carries emotional weight. Large amounts of diegetic sound is also used. Wind across grass, distant trains, , urban city and in each region Suzume visits. They’re mixed forward in quiet scenes so place feels alive even when the frame is still.

Lastly, thematically, the film refuses to “erase” and part of the story. Closing the door doesn’t reset the ruin, but rather it honors it. The final scene returns Suzume to the origin of her loss and suffer, where she meets her younger self and offers the assurance she once needed. This loop Suzume underwent is the movie’s ethical thesis, that remembrance is the maintenance of memory, and the future is the willingness to keep moving forward nonstop.