Back in September, I attended the Emory Cinematheque’s screening of Grey Gardens (Maysles, 1975), and knew I wanted to wait until the week on documentary to fully unpack what I had witnessed. In only 95 minutes, viewers are taken into the home of Edith and Edie Beale, also known as Big and Little Edie, an eccentric mother and daughter duo who are relatives of Jackie Kennedy Onassis living in their run down Long Island estate. The pair argue, sing, perform, share stories from their past life, and seemingly ignore the garbage-filled mess that is surrounding them. Ralf Webb of the White Review discusses the use of direct cinema, the ethics of the film, its historical impact, and more in his 2018 review: https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/film-direct-cinema-grey-gardens-summer/

What is fascinating about this documentary, compared to any others that I have seen, is its commitment to direct cinema, in which they committed to be invisible to the object they were observing without narrative form or musical overlay. In the golden rule, direct cinema is where “interaction with the subjects should never evolve into direction” (Webb). This was exemplified through many shots of Little Edie being interrupted by the calls of Big Edie in the background, or through the subjects consistently talking to the film crews, presenting that they were not restating or asking questions until they got an acceptable answer. Watching this film reminded me of the ethics discussed in class during the first week on Rear Window, however, and how voyeuristic attitudes are only validated when what is being watched has a purpose. This mother and daughter were only relevant due to their cousin’s status, and throughout the cinematheque moviegoers laughed at their remarks, which admittedly were funny throughout the film. Still, there was a clear exposition of two women in crisis, living amongst rodents, and are now solidified in history as entertainers.

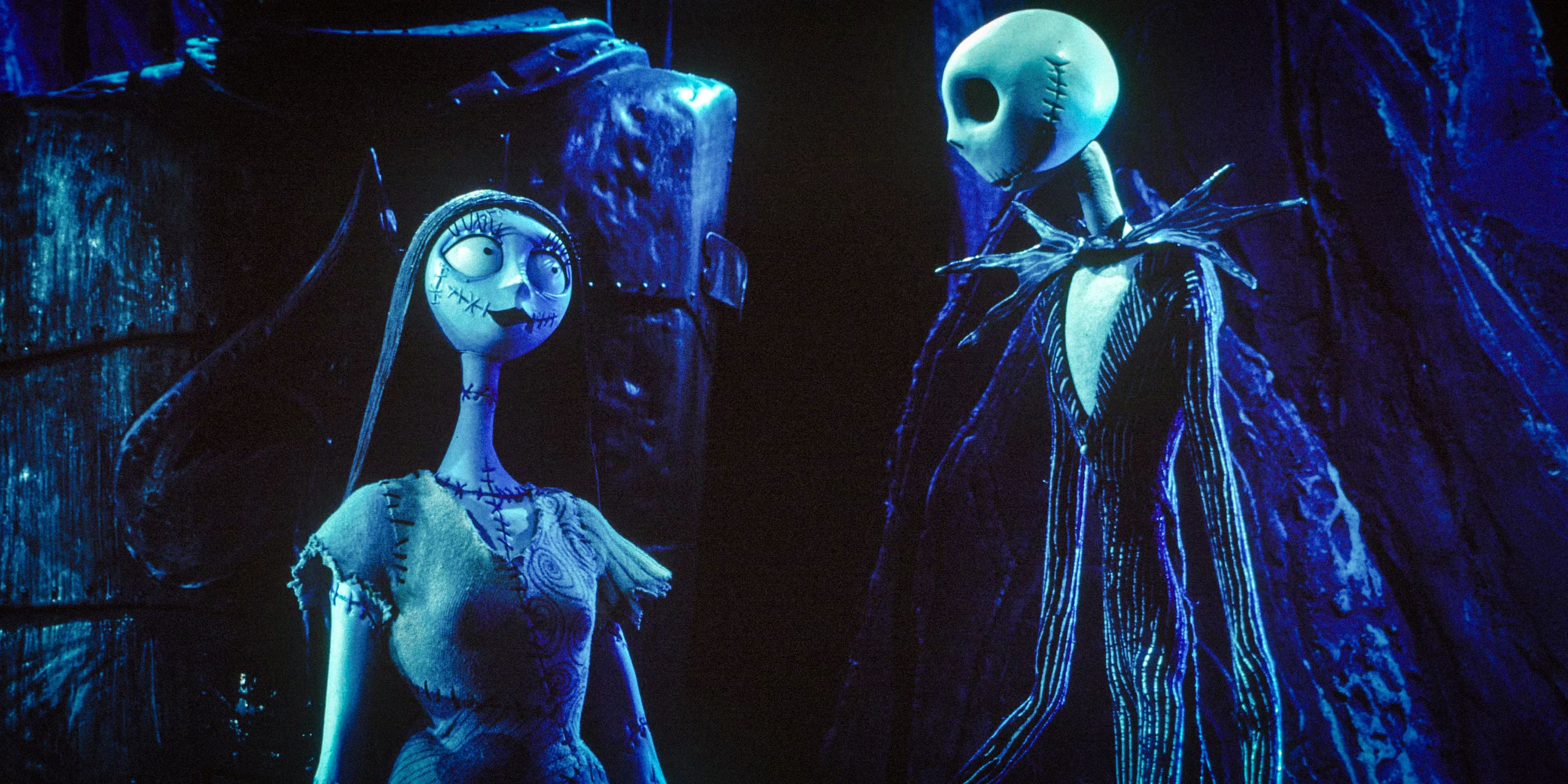

Their story is seen through the eyes of the documentarians, and what is told is manipulated by the production of those making the film, not themselves. The film raises ethical questions because “the Maysles, it seems, are acting in bad faith: they’ve gained the Beales’ trust, maneuvered into their private lives, and act innocently inquisitive, when, in actuality, they’re wise to the documentary gold in front of them. I could not help but think of this when watching Paris is Burning (Livingston, 1991) and wonder if my own entertainment and knowledge acquired throughout the film was ethical. Still, I believe that documentary holds a power in solidifying parts of history that may go underrepresented, and maintain the capacity to amplify voices in ways that would not be for forever. Big and Little Edie do get their stories told to the world, as do the subjects of Livignston’s Paris is Burning that would not be exposed to such a wide audience without the oppurtunity.

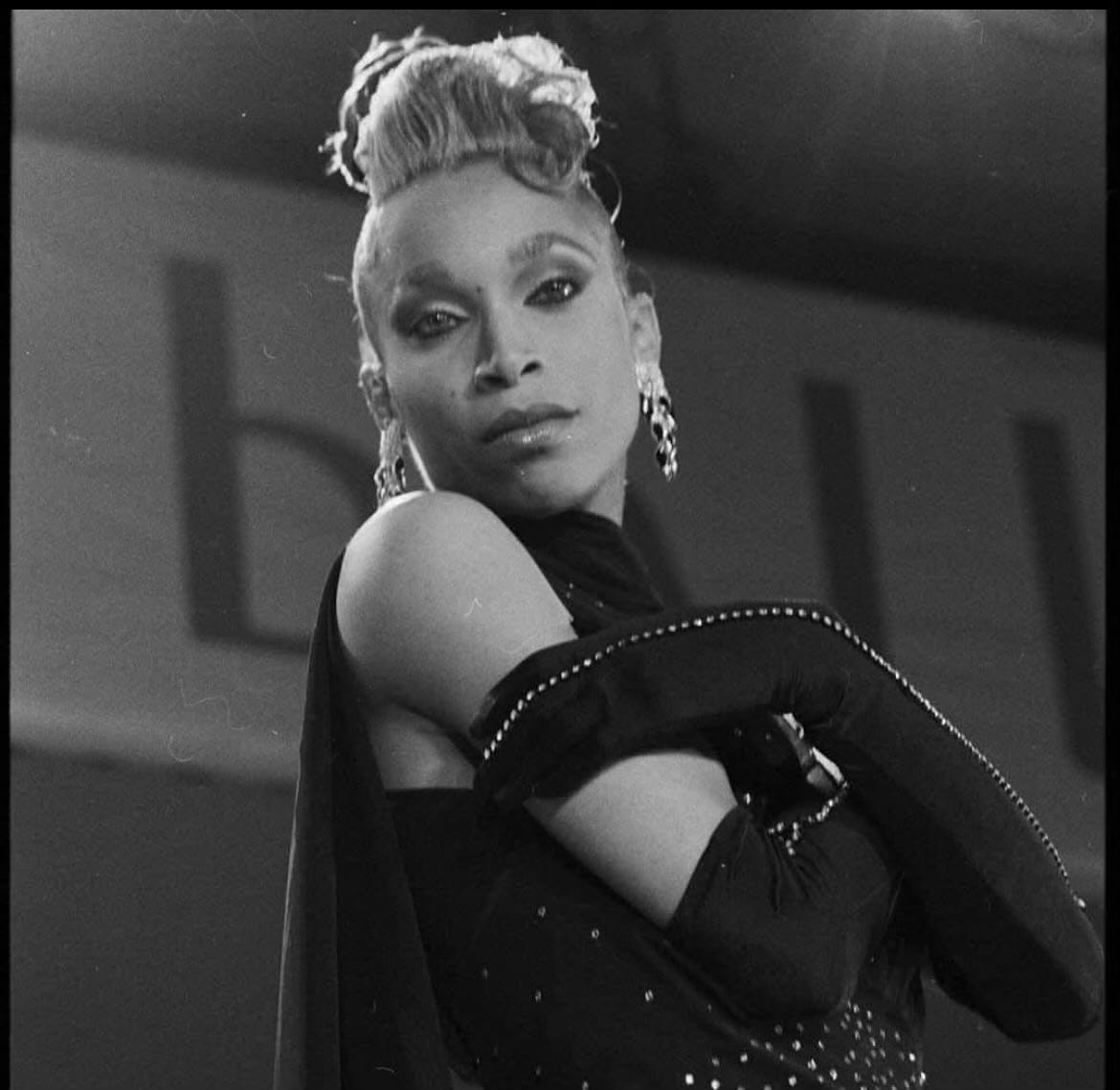

Big and Little Edie have been remembered through movie adaptations, a Broadway show, and drag queen interpretations. After Grey Gardens‘ was released, Little Edie noted feeling accomplished in her portrayal of the film, “as though the power to partly construct a filmic version of her own reality gave her some freedom from it” (Webb). Theories like Webb’s remind us not to look too personally into the lives of the subjects we watch in these films. After spending an hour and a half with Big and Little Edie, it is easy to feel as though one can make generalizations about their lives as a whole. That is just an hour and a half of years of living in Grey Gardens, and the documentary could have been different if filmed at any other point in life.