After reading David Bordwell’s essay “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice”, I couldn’t help but try to compare what I had watched to every detail he described. Of course, it made me curious to figure out which modern movies pass the “test of art cinema.” I landed on Celine Song’s Past Lives. This movie is the textbook definition of precisely what art cinema is, possessing a definite historical existence, a set of formal conventions, and implicit viewing procedures.

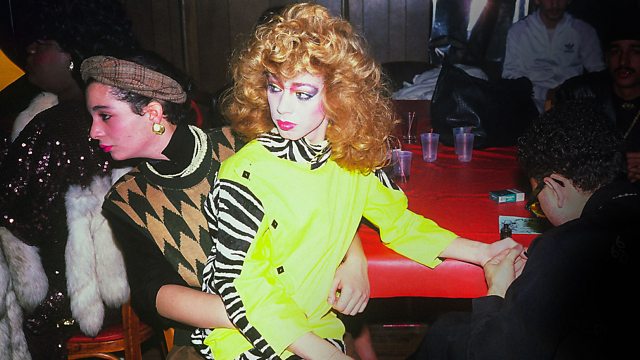

Song does not follow the classical Hollywood cinematic narratives of cause and effect. The narrative is driven by realism and authorial expressivity. We follow the main character, Nora, as she reunites with her childhood friend, Hae Sung. At the start of Past Lives, Song places us in the position of distant observers. Two unseen strangers watch Nora, Hae Sung, and Nora’s husband in a bar, whispering guesses about what their relationship might be: Lovers, friends, a triangle. This moment sets the tone for the entire film: we begin outside, speculating and interpreting, just as those commentators do.

The characters’ goals are emotional rather than external. We see some characters wander out & never reappear, and events that lead to nothing. We are on the outside, watching this story unfold, and a series of flashbacks and flashforwards drives the narrative. Unlike in a classical film, the spatial and temporal elements are constantly manipulated. Like Bordwell describes, the characters often “tell” us what connections mean through autobiographical recollection, as when Nora reflects on her childhood in Korea before emigrating to Canada. We see this in Past lives after the opening scene, where we flashback 28 years to young Nora in Korea with young Hae Sung. We recount her immigration to America, where we meet Hae Sung’s mom. There is a girl on the plane who practices English with young Nora. Then, we flash forward 12 years to an older, yet still young, Nora in New York.

Nora reconnects with Hae Sung through Facebook. We follow their relationship over video calls in different time zones, switching perspectives between Nora and Hae Sung. Yet, as the movie progresses, we question who is telling the story. Song disrupts the fantasy early for the audience of “childhood friends turned lovers”, as Nora gets married to a White American man, and yet, it still feels like she is longing to be with Hae Sung or Hae Sung to be with her.

Past Lives ends where it began, the same street, the same window, but our position has changed. We now see from inside, with a deeper understanding of the characters and their unspoken feelings. The final conversation between Nora and Hae Sung offers the illusion of closure while leaving us suspended in longing. In true art-cinema fashion, Song ends not with resolution but with interpretation. The question is not whether they end up together, but what their connection means to them and to us. In this way, Past Lives fulfills Bordwell’s vision of art cinema: realist, author-driven, and deeply ambiguous.