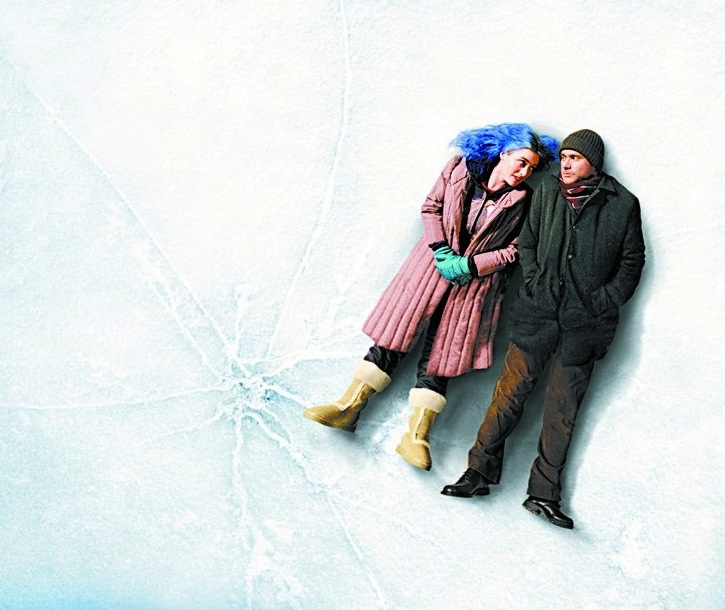

When I go to watch a movie, I always try to enter the theater with the mindset that I’m going to like it, doing my best to block out outside opinions (although, with a film as talked about as Emilia Pérez, it’s impossible not to go in with some bias).

Emilia Pérez is an extremely ambitious vision from Jacques Audiard who, in my opinion, “bit off more than he could chew.” When you set out to tell a story that, while not the central focus of the narrative, involves themes that are so relevant and current in society, it’s essential for the filmmaker to study each of these themes in depth.

And that’s where the film fails, in my view. How can a man who’s been on hormone therapy for two years still have a beard? Small details like this don’t align with the reality of a transition and bothered me throughout the story.

Now, speaking from a musical perspective the film Emilia Pérez left a LOT to be desired. I’ll admit that I liked the first two songs, but as the movie went on, the songs felt increasingly out of place, as if they were an afterthought by the director, disconnected from the story. Their lyrics, unlike those of a good musical, didn’t complement the plot; they were shallow and repetitive.

The duet between Zoe Saldaña and the doctor hit me as a failed attempt at “wokeness,” something that critics somehow bought into, believing they were promoting the kind of “diversity” long demanded by major awards (and honestly, that’s the only explanation I can find for the number of nominations this film received).

I also LOVED the choreography, especially in the benefit scene, which was, by the way, very well directed.

Given the massive controversies surrounding the film, especially Karla Sofía Gascón, it’s hard to praise her—but it’s undeniable that her performance made the film powerful in many moments. I also can’t watch it without imagining how difficult it must have been for her, as a trans woman, to have to dress and act as a man in several scenes; the dysphoria must have been intense. (I’m not excusing the outrageous things she said, just pointing out something I found interesting.)

Lastly, we can’t ignore the blatant stereotypes the film brings—not only about Mexican culture but also about trans issues—something that bothered me but also prompted important reflections about how certain clichés still dominate the minds of critics and voters today. How can these people realize that this isn’t reality when they live in an “Americanized” bubble where that’s the only perspective they know?

Anyway, these are things I feel like the Academy will have to think about moving forward if it truly wants to represent the diverse realities that exist beyond such a limited lens.