One of the most important elements within narrative is the degree of knowledge we as an audience are given as the plot progresses. This degree of knowledge often falls between restrictive, knowing as much as a character, and unrestrictive, seeing and understanding more than they do.

The film begins with a relatively restrictive plot centered around the main character, Truman. We as an audience are aware that he is in a television show through mild exposition in the opening, but for the first half of the film, we experience what Truman experiences. The film invites the audience to piece together the world of Seahaven and it’s intricacies by ourselves rather than exposition; from the sitcom-like interactions between Truman and the cast, to the oddities of glitching radios and falling lights hinting at the artifice. We are active participants of Truman’s gradual discovery that the world around him isn’t real.

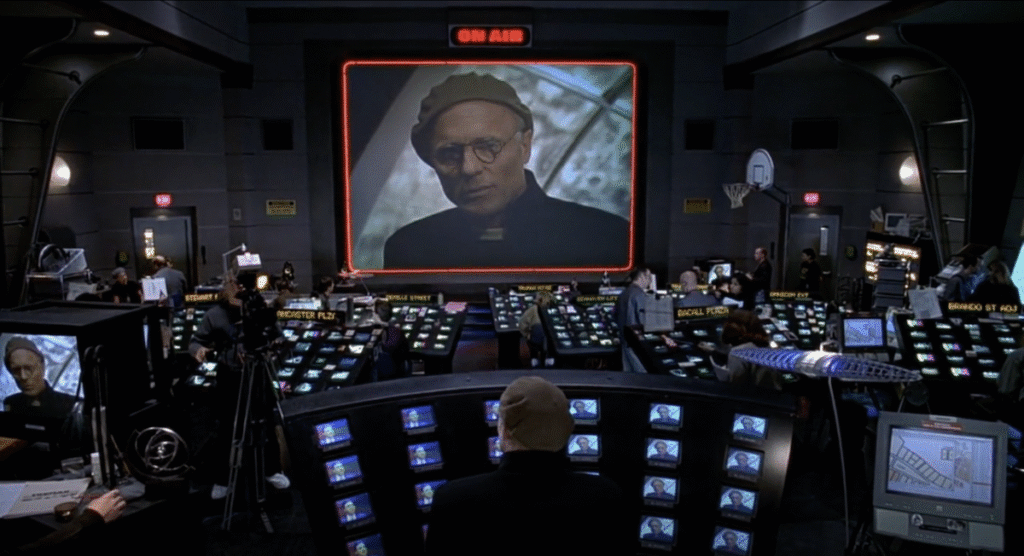

Around halfway through the movie, the degree of restriction drastically changes. During Truman and his “father’s” reunion, the film intercuts the perspective of Truman and the show’s control room. We meet Christof, the creator of the show, and his show-runners as they improvise the direction in real time. Shortly after, a news reel acts as exposition, fully fleshing out how The Truman Show came to be and operates. During an interview phone call between Christof and a former cast member Lauren, Christof tells her “we accept the world that is presented to us” when Lauren calls out the ethical injustice done to Truman.

Had the story began with an unrestrictive lens, Seahaven would simply appear less real from the beginning, and Christof’s thematic stance would appear more intellectual rather than emotional. Instead, the restrictivity allows us to emphasize with Truman, and make the central conflict –control verses freedom– grounded in Truman’s personal struggle instead of overarching ideology. For example, despite the Christof and the showrunners’ numerous attempts to present Seahaven and Truman’s life as “perfect,” we clearly see Truman’s emotional distress and desire for authenticity.

The climax of the film makes the most creative and powerful use of restriction. Truman decides to leave the island and conquers his fear of water as he sets sail. During the night, he sneaks out of the house, and none of the cameras –and by extension, we the audience– know where he is. The story is suddenly restrictive again, but with a reversal of power. We don’t follow Truman’s ignorance; we share the showrunners’. The film itself weaponizes restrictive narration against the audience, implicating us of the same voyeurism that it critiques.

The Truman Show ‘s manipulation of narrative perspective throughout its runtime ultimately becomes both its central storytelling device and its strongest moral statement.