Broadly speaking, my research concerns the epistemological, ontological, and social/political dimensions of categorization. More specifically, I’m interested in how the ways we identify, organize, and present objects aligns with institutional, political, and pedagogical priorities.

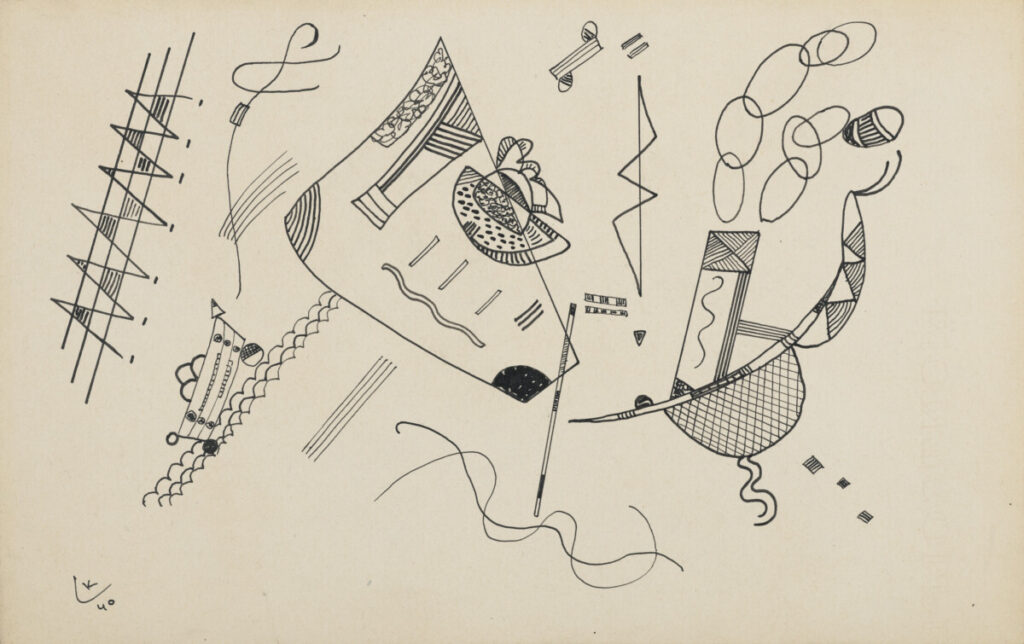

Take, for example, an art gallery. As a curator, I might decide that gallery should be organized around an artist–Kandinsky, say. I’d end up with a space that offers up pieces like these:

[All pictures from Wikimedia Commons]

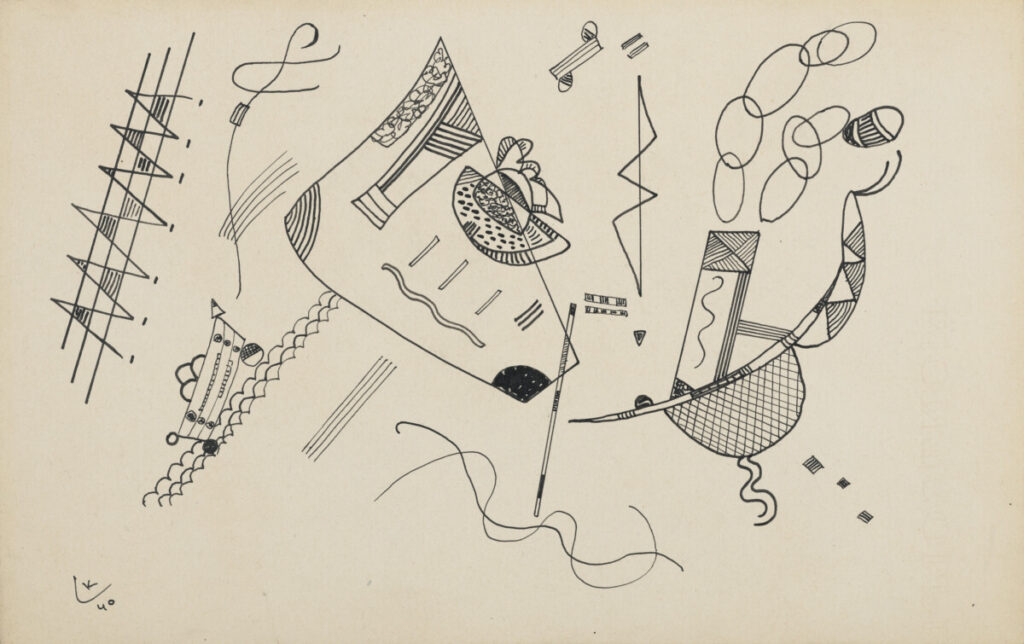

Viewing pieces in this way gives you a sense (maybe a small one though) of the range of Kandinsky’s work. It emphasizes the artist: their approach to creation and how that may change. I could, however, pick an entirely different type of organization–works titled “Untitled,” for example:

[All pictures from Wikimedia Commons]

There’s some overlap here–Kandinsky appears again–but by organizing the works in a different way, we are inclined to ask different questions: what, if anything, do these pieces share? What is the purpose of a title of a work of art–or of not giving a title for a work of art?

The point here is that how we identify, organize, and present objects can lead to different experiences, ideas, questions, and so on.

As a philosopher and educator, I find it fascinating to think about how our educations are organized around the idea of subjects and disciplines–including Philosophy. Within the discipline of philosophy, for example, we find various categories that shape what and how we read, categories like “Ancient Philosophy,” “Modern Philosophy,” “Asian Philosophy,” and so on. How do these principles of organization include (and exclude!) certain texts, ideas, and perspectives? How does such organization norm what is recognized as “philosophy”?

I am not suggesting there is a “right” way to organize and present these things. But I am suggesting that, like with an art galley, there is a significance worth thinking about when it comes to the structure of how we learn, inquire, and think.