In this interview from March 2021, we talked with Professor Daniela Zappador Guerra and two teaching assistants, Mariana Barrios, and Jaclyn Taylor, about their experience teaching Italian as a third language to Spanish speakers at California State University Long Beach. As a co-author of Juntos, an introductory Italian textbook designed for Spanish-English bilingual students, Professor Zappador Guerra gave her perspective on what it means to create didactic materials and what should be included in future materials for Italian L3 courses. Other topics included the variety of students in L3 courses and how to cater to their specific interests and needs, what instructional methods (i.e. explicit vs. implicit) are utilized and when, and how transfer (both positive and negative) affects L3 learning.

- Instructors: Daniela Zappador Guerra, Mariana Barrios, and Jaclyn Taylor

- Institution: California State University, Long Beach

- L3 classes taught:

- Fundamentals of Italian for Spanish Speakers (ITAL 100A)

- Fundamentals of Italian for Spanish Speakers (ITAL 110B)

- Intermediate Italian for Spanish Speakers (ITAL 200)

Interview

How many times have you taught Italian as a third language or as a second language as well, and what types and levels of courses have you taught, such as introductory, intermediate, or advanced?

Daniela Zappador Guerra: I taught introductory, Italian 100A, for 3 semesters.

Mariana Barrios: This is my second semester teaching Italian for Spanish speakers. It’s the first level for beginners, 100A.

Jaclyn Taylor: This is my fourth semester teaching Italian for Spanish Speakers. My first two semesters, I taught the second level (200), and these last two semesters, I’ve been teaching the initial level (100).

What languages do you consider yourselves proficient in, and how and when did you acquire these languages?

DZG: I am Italian, I’m a native speaker so my first language is Italian. Then I learned English when I came to the US. I knew a little bit before, but the strongest preparation came here in 1997, but I also took French in high school and intermediate school, three semesters of Spanish in university, and also one semester of German in university. And of course Latin and Greek in university, because I have a master’s in classics so I studied Latin and Greek for 10 years.

MB: For me, I am a native speaker of Spanish, and I grew up bilingual with English. I grew up in Mexico, and the semester after I moved to the US I started studying Italian, so that was about six or seven years ago. And then I decided to take one semester of French and didn’t really like it. And then I decided to try Portuguese and I loved it. I’m not an expert. I wouldn’t say a C level, but maybe between a B1 or B2 level. I love Portuguese. And I actually took two classes of Portuguese: a regular class for Portuguese and a Portuguese for Spanish Speakers, so I have that experience as background. And then I decided to take French once again, give it another try, and didn’t like it. And then I was doing Romanian, and I decided to postpone it, because I’m trying to learn Russian right now.

JT: So the first six years of my life I spoke English and Spanish at home, and then there was about an eight-year period where I didn’t really use Spanish as much. I went back to it when I started community college. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, I took a Spanish class because I knew there was a language requirement for transfer, and I kind of fell in love with it all over again, so I actually got my BA in Spanish. Before transferring, I knew I had to take a second language, and so I always had a fear about Italian because I was worried about mixing up my Spanish and my Italian. So, I took a semester of Japanese and did really well in that, but I realized that I didn’t have the time to dedicate to the writing, so I ended up taking Italian and then I transferred to Cal State Long Beach. I actually transferred there because I was told about the Intercomprehension program by my Italian teacher at community college, who was a graduate from Cal State Long Beach. So when I transferred there, I took Italian 200, which is the Spanish speakers course, it’s a hybrid course. So, I took that course and then I decided to add Italian as my minor. I finished my Spanish bachelor’s and then I joined the Italian master’s program.

Can you give us any insight into the typical linguistic or academic background of an Italian for Spanish speakers class at Cal State Long Beach? What percentage of a typical class is made up of heritage speakers versus students who learn Spanish as a second language? And is the class only available to undergraduates or can graduate students enroll as well?

DZG: I know that there’s a huge population of Spanish speakers in Cal State Long Beach, specifically heritage Spanish speakers. And, of course, it seems that Spanish is a huge second language here in California; many people take Spanish, and Spanish is offered in any high school. So, there are also students who learned Spanish in the classroom, but I would guess the amount of heritage speakers is greater than those who learned Spanish as a second language.

MB: I totally agree. For me, it’s usually more heritage speakers than students who have studied Spanish in high school.

JT: Yeah, the most non-heritage speakers I’ve ever had in a semester was about three, and that was when I had a maxed-out class, which consisted of mostly first-generation students from the US, so heritage speakers who speak Spanish at home. And then I get some students who, like Mariana, grew up out of the country, and so they learned Spanish grammar in an academic background, but generally that’s more rare. I surveyed my students at the beginning of the semester to get a breakdown, and very few of them felt comfortable with Spanish grammar terms. So I’ve had to adjust some of my teaching, so I don’t overwhelm them because the grammar terms are usually less familiar. You have to use examples because you get very few students who know exactly what you’re talking about when you say something like “This is the compuesto.” Sometimes we have older students, like I have a student who’s 48, and they tend to feel more comfortable with the grammar aspect, for whatever reason.

How do you think the prerequisites (two semesters of college Spanish or three years of high school Spanish or being a native or heritage speaker of Spanish) affect the class setting? Do you notice that most students have a similar level of competency, or is there usually a lot of variation in their levels of competency?

DZG: Maybe Jaclyn in a way answered that question when she said that basically if students never took a language class, like Spanish, before, they are not familiar with the grammar terminology. It’s natural for them to speak, but they don’t have any clue about verbs and adverbs and adjectives, and they don’t do much grammar in English. But I never considered the difference between people who took Spanish in high school versus people who took Spanish in university.

JT: I think there’s a big difference. The two semester requirement at university level generally doesn’t pose as much of an issue but occasionally you get students who take the class because they’re overconfident with their Spanish skills and then you realize they really aren’t at the level that they need to understand some of your examples, and so a lot of times those students either transfer out or kind of fall behind and so it’s really about students knowing themselves and their own competency. I find students who are either language majors or who have taken a language class recently have a better time. They think about it, and they have that meta-linguistic awareness, where they think about it that way, whereas with other students may be taking it because they want to go on vacation in Italy or they just thought it would be fun, they don’t think about language and learning language that same way, sometimes they encounter bigger blocks, even if something’s very transparent to Spanish because they’re just not used to thinking about it in those terms.

MB: I totally agree that they are not used to analyzing their own language. In fact, last last semester, I had a student who had studied Spanish in high school, but we all know that not everyone takes their classes seriously in high school, especially language classes. Some of us love it, and others just take it because they have to. And he ended up changing courses from the Italian for Spanish Speakers to a regular Italian course.

JT: And the second language students are some of the best students sometimes. For example, I had a student two semesters ago, who was a junior getting his Spanish BA and I realized I identified with him a lot, because we both had the same experience in terms of being really into language learning and so he was one of my best students. He spotted things like immediately all the time, more than even heritage speakers, so it very much is a personality thing to an extent as well, or how ambitious you are about your language learning.

Is there any way you can think to improve the prerequisites for such a course, in order to streamline that process, or are varying levels of Spanish, going to be something that’s always inherent in the language classroom?

DZG: Personally, I can tell you that there’s so much diversity in high school preparation. There are students who had a great class, and great teachers and they come over, and they are ready for learning a language and some other students are completely lost. But they seem to be lost in English as well, so they don’t even know how to read out loud in any language, so when you ask them to read in Italian they don’t know how to so it really depends, and the background is so different that I think it’s a little bit out of control. One positive thing we have in Cal State Long Beach at the community level is that we had a chair in our Italian department that was in contact with the surrounding high schools. She invited teachers, she visited classes, and promoted language studies. So that helped because those teachers felt connected with the university. That’s a very important thing: if you can connect the university, with the community and prepare the entrance of some students, that’s a good promotion for language and a good preparation so that teachers felt they were not alone.

MB: Exactly, that way both the students and the Professor know there’s something beyond; it’s not just this little step right here and you’re going to finish high school and that’s it. That way, students know that there is something else that they can continue studying in college.

DZG: I remember there were welcoming presentations done in high schools. I went to one in San Pedro with Dr. Donato, and I noticed that the students were thinking, “Okay, I can continue studying language. There’s a connection between my teacher and the university teachers”, so it works.

MB: And going back to the initial question, there are many different factors that affect the students’ environment, such as socioeconomic status, the kind of Spanish that they speak at home, their parents’ education. Many different things that will always affect the levels of Spanish in the classroom.

JT: I think that disparity in levels of Spanish is unavoidable because otherwise you’d have to get into really regressive testing policies that would limit enrollment in a way that I think is more harmful than having students who are maybe a little behind in the class working to catch up. I think enthusiasm and teacher support can make up for those deficits, whereas if you start having an entrance exam to get into the Spanish speakers class, it would be discouraging and enrollment would suffer dramatically, which we all know, it’s not great for language departments.

MB: Exactly, whereas in this way with varying levels of Spanish in the class, it would work as reconsolidation: you’re learning Italian, but you’re also perfecting your Spanish, for some students at least.

What specific teaching materials so textbooks or any other supplemental materials have been used in Italian for Spanish speakers and how do you choose these? If you’ve ever used the same materials that you would use in a traditional Italian class that isn’t for Spanish speakers, how would these textbooks be used differently, and now, how do you enjoy using the Juntos (Dr. Guerra’s) textbook compared to the textbooks used previously?

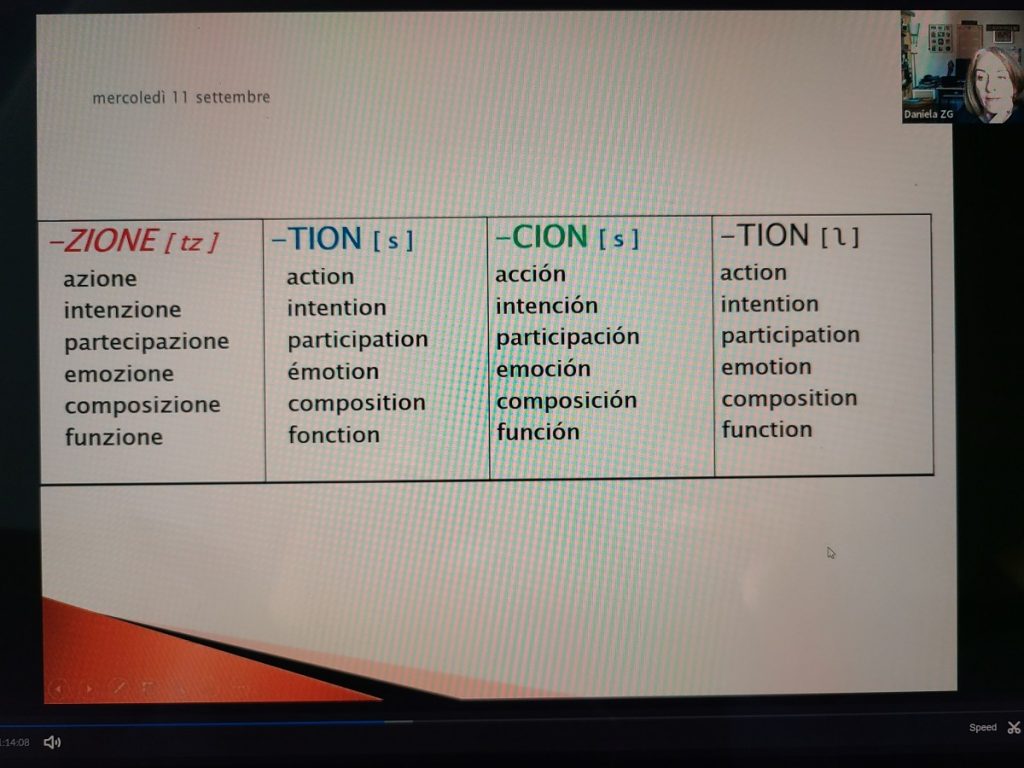

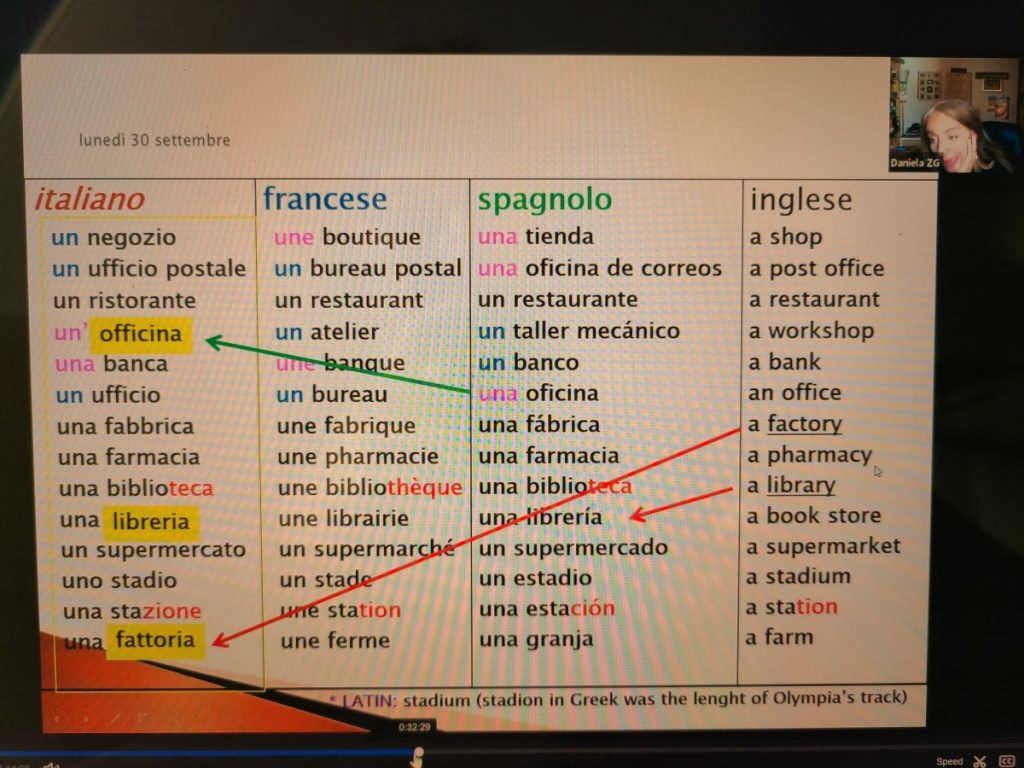

DZG: First of all, when I started teaching a Italian for Spanish speakers, we didn’t have any textbooks yet. We were doing seminars because there were professors from universities in Europe that came over. Pierre Escudé was one of the founders of this methodology of intercomprehension in France. He came over, and I met him and talked to him. So, Dr. Donato was inviting those experts because she has connections all over Europe. So, they were coming, and we were doing seminars with these guests and also among ourselves to discuss what kind of materials we could use. We exchanged materials, but at the time we were producing our own stuff. In fact, before becoming a book like you see now, Juntos was an electronic book published by redshelf.com, which is our platform to publish books from professors, and we were using that. If you let me share my screen, I want to show you some of those first materials. This was one of the first PowerPoint I created for my class. For example, see how we were directing attention to the similarities in endings, so that there are transparencies (see Image 1).

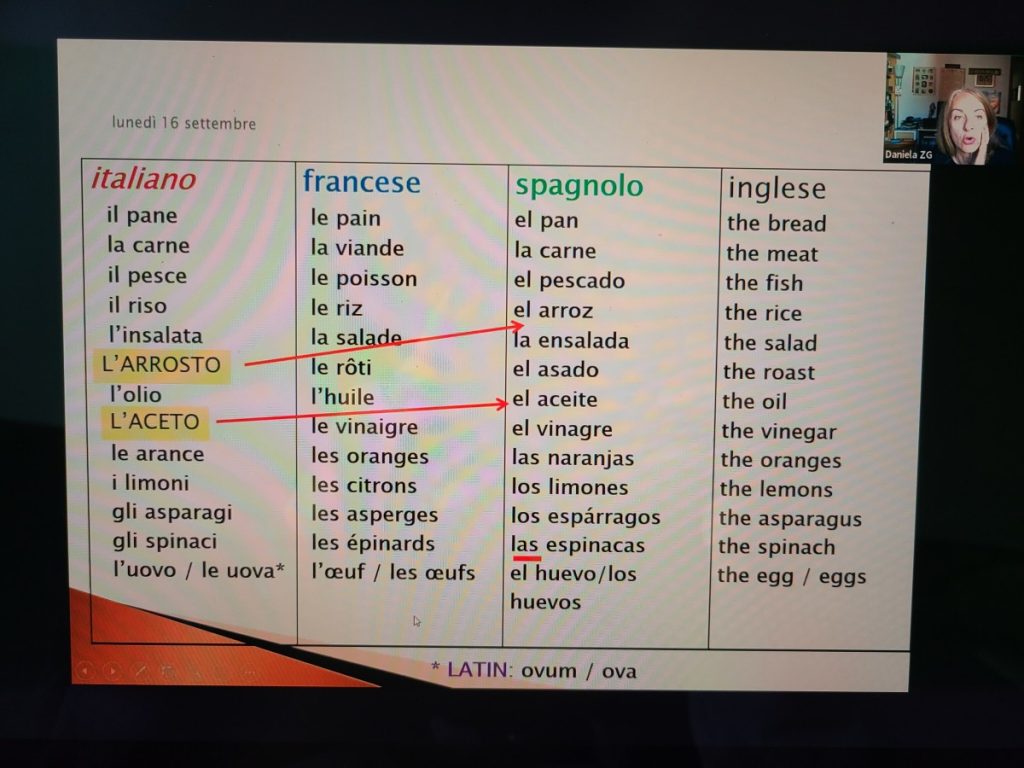

Here, I was giving them a list of words in Spanish, in English, and then I was giving them the French and Italian and they had to discuss – there was a big discussion in the class – they had to look and see what sounded and looked similar or completely different (See Image 2). At one point, I asked them to look for what was not really transparent. For example, this one (l’arrosto vs el arroz) is completely different, it’s a false cognate basically, or this one (l’aceto vs el aceite) is a false cognate as well. It can be confusing, but it was interesting because you point out the big differences and it sticks, especially if you do little jokes with them right. Say you put together some ingredients that you think are one thing, and they are completely different.

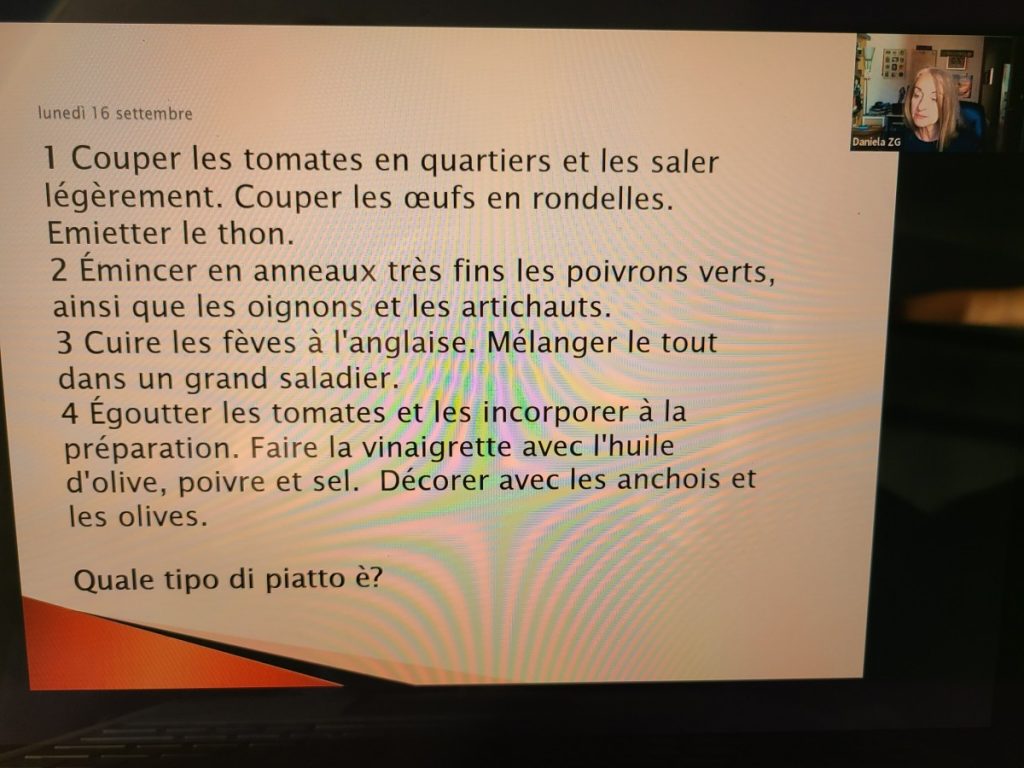

In this example, none of the students knew French, but I put a text in French (See Image 3). And first of all, I asked them, “This is about food right?” You can recognize it is about food, even though you don’t know French. And then I asked, “What kind of dish do you think this is?” And so, they had to guess. Little by little, these opaque texts became more clear. And so, I said, “Try to write it in your own language, it can be Spanish or English or Italian.” And they did! They were amazed how much they could understand from a text in a language they didn’t they didn’t know at all. That’s why I chose French. And then, we were pointing out the ingredients, and they guessed it was a salad because there was the “vinaigrette”, and we were talking about the aceite and oil and olio and all that stuff, so the attention was already on that item.

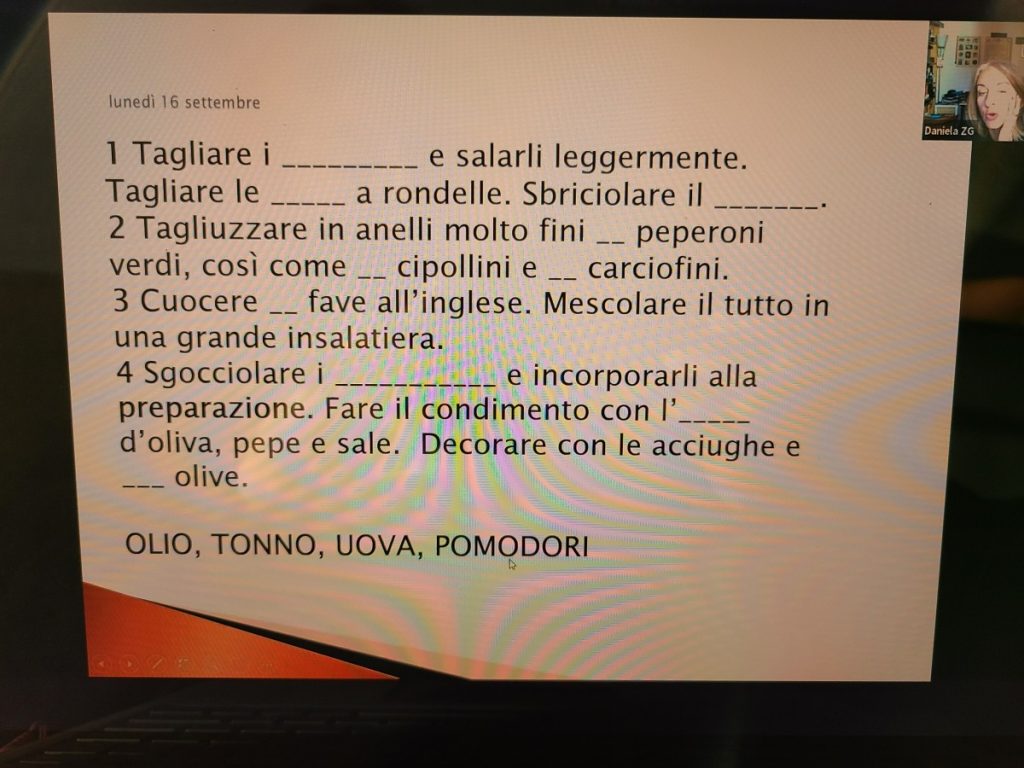

And so, when I gave them the translation in Italian, they were also able to put the right ingredients in the right position (See Image 4). But notice how we moved from French to Italian.

And we did the same thing with other words to see and look at some funny differences (See Image 5). “Oficina” is always something they mix up – they say, “I do my homework in my ‘oficina’.” and I say, “Wow, are you a mechanic?”

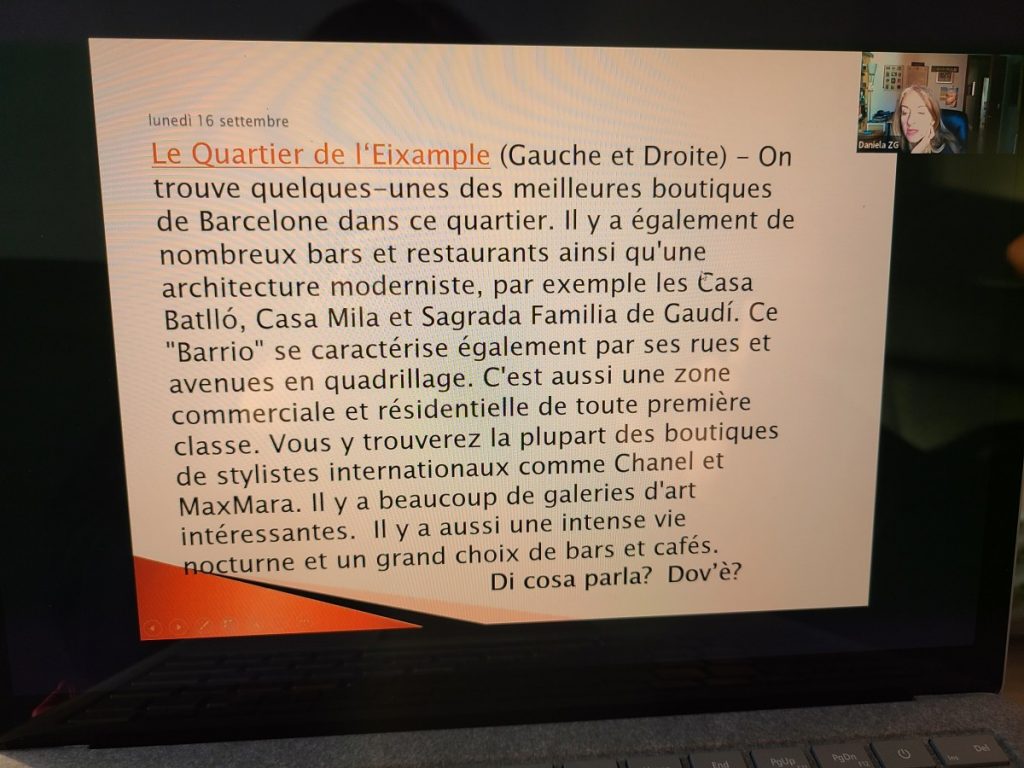

And again, there was a French text that talks about Barcelona, but actually in French (See Image 6). So there’s also this intercultural thing – you can talk about something that is not French, in French. And they had to guess what was the content of this, and they could guess – because there’s “Chanel”, “MaxMara”, “Barrio” and “La Sagrada Familia” – so they could guess.

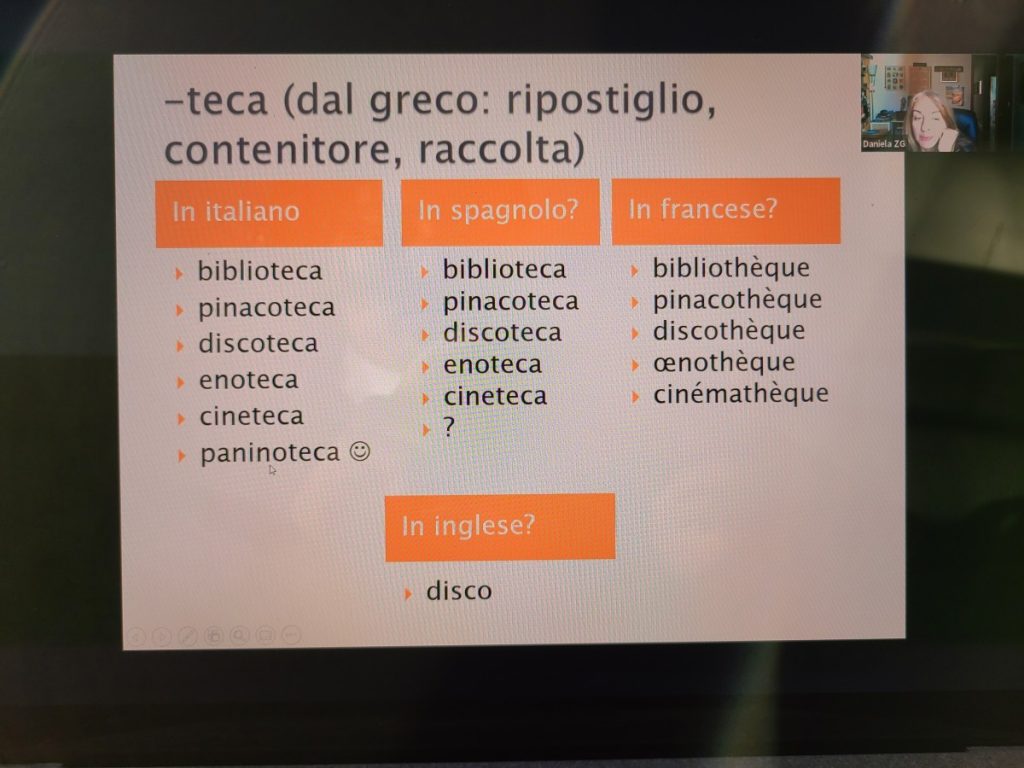

And we were talking about the words, and they learned, for example, that there’s this “-teca” suffix that applies also to creating new words that don’t exist in any translation – like “paninoteca” – what do you think this is? It’s a word for a sandwich shop – this doesn’t exist in any translation or any language. So we create new words using suffixes (See Image 7).

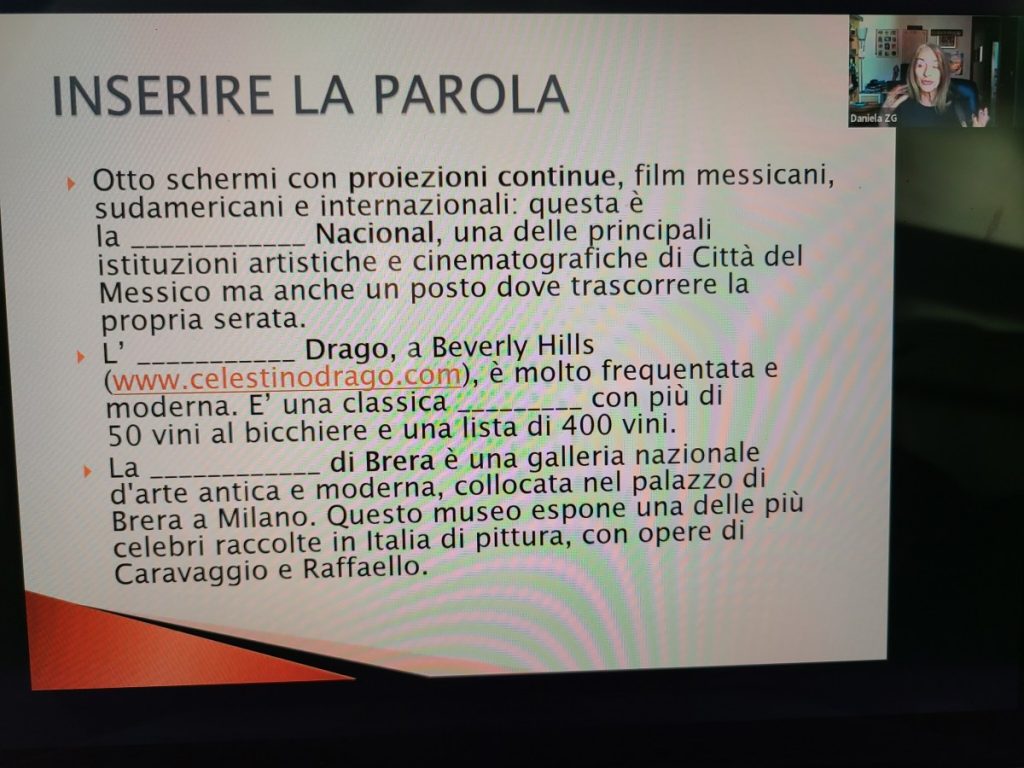

So, this is navigating through language – it’s translanguaging, we are going from one language to another. And then we were emphasizing some words, and then they had to put the words in, in Italian again (See Image 8). So we got to the final text that you find in any grammar textbook – regular textbooks, what do they have? Fill in the blanks – here are the words, put the words inside, and I’ll give you the English translation of the word. But here, it’s completely different – you come to the word through different languages, languages that you don’t know, and at the end, you do the exercises that a normal textbook would give you, but in a completely different mindset. So that was before Juntos. It was like – “okay, let’s explore and see how they react”. And what do you think was the feeling of these students? They felt like they knew more than they thought – like “if I want, I can really study French”.

MB: You feel like you’re capable – and that’s different.

DZG: This intercomprehension methodology is more than just learning a language. It’s helping students build up their own self confidence in studying languages. Mariana and Jaclyn – what is the reaction of your students? What kind of material do you use? You’re using the book, right? I want to hear that!

MB: Well, I love Juntos; it’s just so nice. Last semester we were still doing a hybrid between the online Juntos version and the Percorsi – which is just regular Italian for English speakers. But we could definitely see the difference, in the engagement from the students – I just love when they come and ask” Oh, is, does this mean this in Portuguese, or is that how it works in Spanish?” And they just use it to compare and I find it to be so useful. For example from my own experience when I learned a Portuguese, I took both the regular Portuguese class and the Portuguese for Spanish Speakers, and even from my own experience right there I could tell that you spend less time in the Portuguese for Spanish speakers course with concepts like “conoscere o sapere” or “conocer y saber” – which are the same word in English, but not in Spanish, not in Portuguese, not in Italian. So that is one of the things that I love from Juntos, that you can go through those concepts quicker, and they recognize it – you’re not just explaining concepts, you’re showing them: “Hey you know this already, this is easy for you – let’s look at it in Spanish, and then there you go same thing in Italian – you’re already doing it” – so I feel like that’s very encouraging for students. I mainly use the book, Juntos, and PowerPoints, sometimes I add some vocabulary lists so that they have more to talk about. But I find it very useful and it has different kinds of activities, so I really feel like you need to know your audience, you need to know your students and so sometimes you will be using more of the translation and sometimes you will be using more of the reading, and sometimes you will be using more interactive things. But you have all of that, so I really, really enjoy that. It just depends on how you’re seeing that your students are learning more, you can go more towards those methods.

JT: I would agree with what Mariana said about Juntos, and it is very much about knowing your audience of students. I integrate a lot of the exercises into homework. During class since we’ve been on zoom, I use Powerpoints; when I taught in person, I actually was pretty minimal with Powerpoints and was more doing the work on the board with students. If I want to integrate extra exercises or examples into my Powerpoints I actually utilize an old book I have: “Spanish Grammar”. So, if it’s a very particular transparency or difference that I want to highlight, I go back to some of my undergraduate Spanish stuff, especially when I taught the other levels with teaching the subjunctive. I don’t have experience teaching the subjunctive with this version of Juntos, but I’ve looked through the book and I’m happy with it. For when I taught in-person, with Percorsi, we have an online lab for homework, but in terms of in class exercises, I kind of pulled from everywhere at that point – sometimes I would pull from the Mondadori sites, so actual Italian learning sites for exercises, especially when it was idiomatic-type things. I find this textbook covers that, like idiomatic presents with “avere”, they’re pretty transparent so that was something with this version of Juntos – and the previous on. It’s very much about your students. I really like the number of exercises and the variety of exercises in Juntos ; I really like the translation stuff, so sometimes I’ll integrate that into class or sometimes it’ll be part of the homework. It just depends on how you like to teach as well.

DZG: There are subjects, for example, the possessive adjectives – that’s always a problem because we use the article, and they don’t. But even in Juntos we teach them strategies: start from your Spanish. Instead of saying “Hey, your Spanish is wrong, don’t think about Spanish, Spanish will make you make mistakes. No!” Start from “mi”, and remember that you have to add something. Start from what you already have, and you add a little ending and an article. It’s not like starting from scratch, you already have a little thing that you can use.

MB: And in fact for that one, I taught that last week. I remember, we have a very specific like: Yes, you don’t use it for “mi, tu, su,” but we use it for “nosotros”, “vosotros” so then they’re like “Oh that’s true, I just say nuestro, or nuestra, or nuestros or nuestras, whereas the other ones are neutrals.” In that way, it becomes easier for them, you know you’re highlighting those things that instead of making it like, “No, no, no, this is different don’t bring this from Spanish”, it’s more like “Hey look at it, you have it, you understand it, just apply it in this language and it’s beautiful”.

JT: I will say, sometimes the things that don’t seem transparent to students are very interesting. Every other semester, I feel like I get a group where “piacere” is very transparent and other semesters where, for some reason it doesn’t click even though it functions the same way as gustar. You just sometimes get a bunch of students, where they’re just like “I don’t get it.” This semester is going kind of in the middle and I am having to say well you don’t say “Me gusto la manzana right?” That is trying to point out like, “Well if you said this in Spanish, wouldn’t it sound weird to you” – and that’s going a little better, but it’s always funny which things kind of trip up students each semester, always something that you don’t anticipate. It’s exactly the same just in Italian and and they’re just like “I don’t get it”; it happens every semester so you have to anticipate that and prepare for that.

MB: Yeah you have to know those difficult topics and another resource that I didn’t mention, and I think we all use it, is Kahoot, so that came to my mind, right now, that we’re talking about “piacere”, because that’s how I got my students to understand how “piacere” works, we went through so many Kahoots and it’s like “Okay, do I use ‘mi piace’ or ‘mi piacciono’”, and they practice so much, and they want to be on the podium, and I feel like it’s so interactive with the colors and the sounds and they really get excited, and they get the concepts. In the next class, they were getting all the answers right so it’s a great method.

What would you like to see more of in any future materials created for third language Italian courses, and do you know of any materials made for intermediate or advanced courses for Italian for Spanish Speakers, and do you think that higher level materials like that would be useful?

DZG: Well, I know Juntos, and we are using this and we built it when there was nothing else. But, what we definitely need is an online platform, because we built this book with exercises and actually Hackett Publishing offers exercises that they can do and activities they can do online. Actually, the book we were using before had a platform online on Pearson, with all the exercises they can do, and the system corrects them. It’s always useful but it gets very expensive and it has to be sophisticated. If it’s not sophisticated, then it’s better to not have it at all. You know, we are so spoiled with Pearson so now, when we switch to another platform, I feel it is not the same level: the interface is not that beautiful for example. That’s what’s missing, we need more online.

MB: I totally agree. So, last semester, I was still using the Pearson – the online part – so they could do the homework there, and honestly, it is very useful because it’s a very quick and easy way to have them do their homework, practice little concepts with little exercises, that don’t take that long. So, yes I would definitely agree that that’s one thing that’s missing and books for the intermediate level courses as well.

JT: Yeah, online exercises that are auto-graded are obviously useful to instructors because it saves us time. This semester, I do find I spend more time grading homework, but that’s okay. The one thing that I would probably like to see more of is more task-based exercises just because I think those are really useful, so I actually integrate those into my discussion boards every week. So my students have a task. For example, I had one where I said, “Imagine your friend who studies at La Sapienza needs to find a two bedroom apartment in this price range, near the university or near a metro station” and so we had learned about the terms of the house, the rooms, and traveling around the city and how to use Google Maps to determine that, so I gave them that task, and also previously in class we had pretended we were finding apartments in Rome, using one of the biggest rental sites and learning the terminology used. I think stuff like that is useful because even if you don’t necessarily see yourself renting an apartment in Italy, you might one day and you get to also give students that fantasy aspect of it, where they’re excited because they’re like “Oh, the rent is really cheap here, compared to California” and they start thinking about it, and get excited about Italian and traveling abroad because they’re like “this is doable for me” and and it’s a practical task. I think people are reluctant, sometimes at the beginning levels to do task-based exercises – they’re like “Oh, that seems too advanced”, but if you’re traveling abroad, you have to know how to do certain things, no matter what your language level is. When I first went to Italy, my Italian was so-so, and I didn’t have Internet access so I had to figure a lot of things out on my own. And so, if you can make students feel empowered to go on an Italian website and understand how to buy museum tickets or read an actual hotel’s website in Italian and understand what they’re looking at, I think they get a lot more interested in vocabulary that can sometimes seem really dry. So that’s the kind of stuff that I think we can integrate at the lower levels even more.

DZG: I used to ask my students toward the end of 100A to write emails to bed & breakfasts In Italy and ask questions, and they got points if they got a reply. And that was real – I mean, it’s real. So that’s what we need, sometimes books just give you mechanical exercises that don’t have any meaning for them. But that’s general, it’s not specific for the Spanish speakers, we do it generally.

JT: And this textbook has a whole section on tourism tips, so I integrated that into that week of instruction. So the book is great, because where there were topics that I would normally include on my own around the same time I would teach other grammar topics, I found those topics in those sections in the book already – so I’d be like “This is perfect because I’m already talking about immigration and look, immigration is the topic in this area.” So it’s nice because there are certain topics that naturally come to mind when you’re teaching, that you think about even from your own experiences learning where you’re like “Oh, I wish I had known how to do this when I was dealing with whatever thing” and the book does that, which I’m really happy about.

What is the balance of language use in the classroom between English, Spanish and Italian? What roles do English and Spanish play in particular, and how does that change throughout the semester and throughout the whole sequence of Italian for Spanish speakers?

DZG: Well, I would say that with the new methodology, we are less afraid to use languages that are not the target language. Like before with the communicative method, we were just forbidden to use any word that wasn’t Italian. Now we feel more comfortable. In Italian for Spanish speakers, I think that other than Italian, we use more Spanish than English.

MB: I think it depends on the classroom. Once again, you need to know your audience. I usually survey my students at the beginning of the semester if they prefer – obviously the class is going to be primarily in Italian, because that’s the target language – but when we need to explain the concepts in further detail or something, what language do they prefer and the majority of the time, it’s English, for my students.

JT: I have a similar experience, where depending on the class, I will use more or less Spanish because you do get classes, where even though students know Spanish and they speak it at home, they don’t feel as comfortable with it, and or maybe more recently they’ve learned the English grammar and so it’s easier for them to understand a grammar explanation in English,. But it really depends on the class – some classes I’ve used almost exclusively Spanish and Italian. In other classes, it tended to have more English, but Italian was the primary focus. It really does depend on the mix of students you have because if you have students who speak Spanish very casually at home, but they grew up in the United States, they went to high school in English, then the dynamic can change because sometimes they feel lost in two languages – which you want to avoid. So it’s highly subjective.

DZG: It also depends on the type of activities you’re doing, I guess. As you said, if we’re getting into grammar, it’s easier to just explain and then it depends. Sometimes it’s in Italian, sometimes in English, and sometimes in Spanish. For vocabulary, we use Spanish. So it depends on the subject.

So regarding grammar – how much of this is left to be discovered by the student, and to what extent, or is most grammar explanation or instruction explicit and contrastive between the languages?

DZG: In my experience, and in my ideal class, grammar comes from the students. Either, because we are doing something that at one point requires a grammar explanation, or because they ask for a grammar explanation, because we are not teaching kids, we are teaching adults, and adults generally are curious about the mechanism, and they want to know how the language works. So they ask questions or they need a structure to understand and to be able to move more comfortably within the language. So it comes from them, it’s not that I just go there and say: “Okay today, let’s talk about the past tense.” It doesn’t work that way. We read a piece, we read something and then we start from there – “Look, this is a story. Is it now, or is in the past? What kind of past? Do you think the verbs that look the same, or not? Look at the words, some of them have one form, and some of them have another form – why?” And then the grammar comes up, little by little, but it comes from something that we need to understand.

MB: I don’t have much to add, but I totally totally agree, sometimes it comes from the students, sometimes I find myself teaching both Spanish and Italian because of their own questions, but yes, I totally agree.

JT: I think the only areas where I can get fairly explicit with grammar is when I’m teaching object pronouns. I tend to try to be more explicit, because building that question structure of “this pronoun answers the question ‘what’ or ‘whom’”, so that they can identify it. Sometimes if you don’t do that, it gets harder for them, whereas if you say “Okay, look at the verb, always ask yourself, “She buys what?” That “what”, the answer to “what”, is your object pronoun, so that’s the main explicit one. When you get into more advanced grammar you can kind of do that too, especially with the subjunctive, or if you get to teaching it, when you’re talking about agreement of time, when you’re using subjunctive and conditional, the imperfect subjunctive, things like that. But they’re going to go over it again in Italian 200, so your expectations have to be limited, like “I’m introducing this to you and you’re not going to grasp it right now, you might not even grasp it until a 300 level course”, but putting the framework there is important. But, especially with the present tense, it’s pretty clear what the grammar is, because it is very transparent.

Do you find that interference, rather than positive transfer from Spanish, is more likely when it comes to learning linguistic structures that are similar to those in Italian or structures that are completely different? And how do you deal with them or correct them in the classroom?

MB: For me, I think that’s when not using the absolute communicative method is useful. Well, first of all with the Juntos book, it’s so beautiful because you get Spanish, you get French, you get Portuguese, you get so many points of comparison, and you get English too. So that is great, and you get to explain to your students that English has a really strong Francophone influence, so you can notice it from here, you can notice from there. And, as I mentioned before, I feel like this method really encourages them to not see their Spanish as an interference, as something bad, as an “I’m getting confused, I don’t know which language I’m using” but more of an “Okay great, I’m using my Spanish to build up on my Italian, to keep climbing”.

JT: I would agree with that because I also give a lot of personal anecdotes about how when I was learning Italian, I was doing my Spanish degree, so I had Spanish in my head all day. And when I went to Italy, I was with people who only spoke Italian, they didn’t speak English, and so I used my Spanish to almost guess sometimes, and I would either say something or spell it out, and then the people I was there with me would be like “Oh, do you mean this?” and I’m like “Yes, I absolutely mean that”. Being able to transfer that structure really helps the students see that as “Okay, I’m not going to be lost entirely if i’m in a situation where I don’t know”. But I do think interference can come into play at the higher level, especially with the subjunctive because it is different in terms of usage from Spanish. My own experience of interference, I found at a certain point my Italian started to interfere with my Spanish.

DZG: That’s what I wanted to say, Jaclyn. So students, sometimes they say, “Oh my god, now Italian makes me confused in Spanish”.

JT: Yeah, with “essere” and “stare” in particular. When I went back to using Spanish all the time, I would suddenly doubt myself about whether I needed to use “estar” or “ser” and would be like “Oh no”, because in Italian it’s generally “essere”. So, you kind of also prepare them for that – you go, “look it might fiddle with your Spanish a little bit, but people are going to understand you, it’s okay” and so the anxiety kind of lessens.

DZG: I think they are more optimistic about the fact that there are similarities and transparencies that make them feel confident, rather than being afraid of considering their language an interference in learning Italian. So, it’s more over on the positive side.

Finally, what are your favorite aspects of teaching Italian for Spanish Speakers, and what are some of the aspects of the course that students enjoy or benefit from the most?

DZG: I like the intercultural aspect. I like when the language helps really to understand each other and compare different cultures. So, I like when we are, at any level, reading or just comparing practices in different languages and in different cultures. Language is an expression of how we act and we think. It’s not just something that is separated from the rest of the world. I’ll give you an example. There are still nouns that indicate professions that don’t have the feminine gender. That’s culture. Why don’t we discuss that? Can we discuss that? How is it in Spanish? How is it in English, is it the same? Is it different? Sometimes we create new words with the feminine version, for example, Minister. The Minister of Culture, the Minister in Italy is ministro. But now there are so many women, they have “ministra”. But at the beginning, that “ministra” sounded so weird. It sounded like “minestra”, which means soup. So there’s always resistance to accept modifications of the language but it’s the culture that creates the language. It’s the culture that needs to modify the language and that’s what I think is the most interesting part for me when we compare, for example, proverbs. We do a lot of proverbs. We ask students, “Do you have that proverb in Spanish?” Sometimes, yes, because proverbs come from the farmers, life, and contact with nature. Yeah. Sometimes they ask their grandma if there is a proverb in Spanish that is equivalent to the Italian one so we compare. Through the language we understand each other and become more tolerant and we understand that we are not that different. That’s the main purpose of learning a language – not just learning for learning. It’s something that maybe unites us instead of dividing us. So, I found this new methodology very useful towards this kind of goal: to be together and understand each other and compare our cultures and respect them. That’s the aspect I enjoy most.And for Spanish and Italian it’s easier. For example, we were talking about flirting. How do you do it? What it’s like being a gentleman, opening the door for a woman or giving flowers, all the stereotypes. Stereotypes! For example, we talked a lot about stereotypes in all the cultures, we compare them, and students relate a lot with that.

MB: There are so many similarities also. Right here in California, there are a lot of Mexicans, and I find so many similarities between Mexican culture and Italian culture. It’s really beautiful. Leave the languages and that’s a different experience – going from “we’re going to grammar” and “we’re going to learn a language”. That’s how we got this very ugly impression that learning a language is so hard, so boring, and not an easy thing to do. Whereas when you get to really learn the culture of the language, experience it, feel it, and really fall in love with it, it gives you a very different perspective. We even learn things about our own cultures.

DZG: I want to ask you two, since I never had the occasion to ask you and you’re using our book, what do you think about the intercultural pieces for reading? I really did a lot of research to compare the cultures.

MB: I can tell and I loved it. For example, I didn’t know Mexico was the number one producer of organic coffee and the world, and I read that in the book.

DZG: Anytime I chose a topic for the reading pieces, I researched different countries that speak Spanish that I wanted to compare. I discovered so many things and for the students it’s important. I swear to God there’s nothing like that in any other textbook. They’re usually only Italian centered.

MB: Usually it concentrates on one single topic, so you’re going to read this and it’s either about the culture or about the tenses you don’t want to read. But over here, you get the diversity which is what I really love. Sometimes you get German words but they explain so much. You get to see how beautiful languages are- not just this class that you have to take, but how they really affect the way we live, the way we think, the way we do everything.

JT: My favorite part of teaching it’s partly about the cultural comparison. I love integrating cultural videos and documentaries. The textbook has a section about emigration and immigration as well. Every semester, for the last two or three, I’ve included a documentary about Gambian refugees in Italy. For our class in particular so many of our students are either Dreamers or their parents came and immigrated for various reasons. So I have them watch the video, which is in Italian, I ask them questions about it, I use it for teaching large numbers as there are a lot of statistics in the video. At the end, I asked them: What do you feel like you learned about this? How does this compare/defer to your notion of immigration in the U.S.? So part of it is we do want to maintain a romanticized notion of Italy because we don’t want students to feel negatively about the culture of the target language at all. But, it is also important to not, you do want them to be aware that it is a country like any other. It has problems and issues. Seeing the ways that it relates to their own experience in the US, there’s tons of parallels in politics and in topics like immigration with Italy and the US that people don’t necessarily think about. That’s something I really enjoy because I get a lot of students who are criminal justice, sociology, or psychology majors and so they’re very curious about that aspect. So I really enjoy integrating videos in Spanish about the exchange of people from Mexico going to carnaval and talking about it in Spanish. It’s fun to kind of round out your course with a lot of different types of material. That’s my favorite part, thinking about course design.