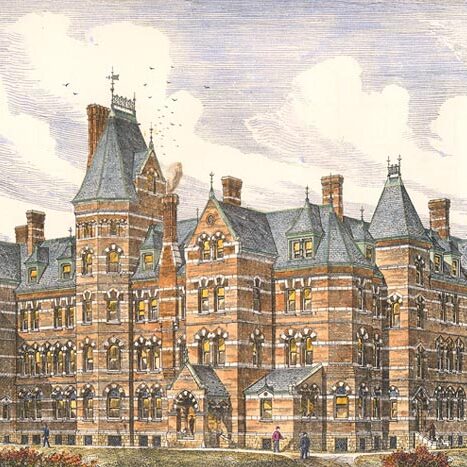

While there were a single digit number of specialized psychiatric institutions and hospital wards in 1800, by the close of the nineteenth century there were hundreds of private–and about 150 public–asylums across the United States. At their foundings, these institutions were heralded as practicing “moral treatment,” a relatively novel psychiatric approach which eschewed physical restraints and claimed to “cure” patients of their madness through gentle management and care. However, many of these institutions were also sites of patient abuse and overcrowding, leading to constant pressure for asylum reform from leaders like Dorothea Dix over the course of the century.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, eugenic ideology was equally popular in the United States as it was in Europe. A consequence of this was a widespread fear of disabled and mentally ill people, which lead to the ballooning of institutionlized populations. As custodial institutions took on more and more patients–sometimes having double or triple the number of patients designated by their original maximum capacity–living conditions at these institutions became increasingly inhumane. Not only were patients crowded and subject to dubious psychological treatments–such as electroshock therapy–but they were also subjected to surgical sterilization and medical experimentation and research, both performed without consent. The abysmal living conditions and abuses of twentieth century institutions led directly to the deinstitutionalization movement of the 1960s.

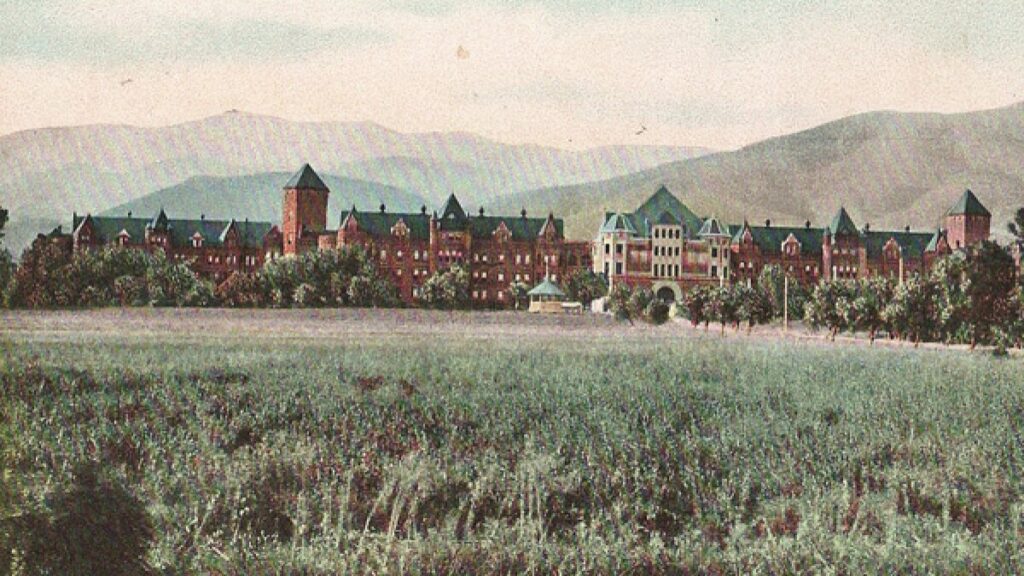

Today, in a post-deinstitutionalization era, many nineteenth-century asylums still stand, converted into artists retreats, homes for veterans, shopping malls, rehabilitative centers, and prisons. The goal of this map is to tell the macro history of these institutions, to emphasize the networked connections between them, and to provide a comprehensive bibliography of scholarly work which illuminates their history and honors their inhabitants.