Upon first glance, the Miscellany manuscript looks unexciting and more deceivingly unimportant. What drew me to the manuscript was the fact that it was, refreshingly, not Christian and though it was written in Hebrew, it was not based directly on religious text. This piece actually contains a large conversion manual from the Jewish calendar dates to non-Jewish dates (The British Library, Polonsky foundation catalog). I can only assume how revolutionary it was to be able to connect the lunar calendar to other time references. It was interesting to note how easily this manuscript could have been overlooked but with thorough examination, I was able to recognize just how important this text was and the also who it may have been so important to during the 14th century.

Initially I inspected the physical aspects of the document. There was nothing exceptional about the outer appearance so it was not a book to be put out on display for ceremonial purposes. However, the size of the book was a bit larger than our books today at 280 x 200 mm (11 by 7 inches) indicating that it was important in its own regard. It was not small enough to travel with or big enough for ritualistic exhibition, possibly suggesting that it was intended for single-person utilization. This could be in the case of a curious religious leader studying it, or in the case of later medieval studies where information was copied by scholar until a final book was created through his own efforts. The pages were made of vellum or calf skin which according to Barbara Shailor, were “especially prized for deluxe manuscripts” (The Medieval book pg 9). The 97 folios most likely took several calves which were not inexpensive, exposing that this was a fairly costly endeavor. This was my first indication that this book was more than what met the eye.

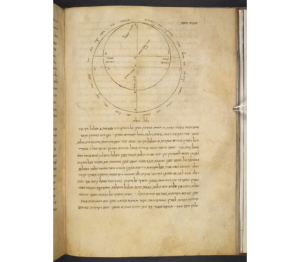

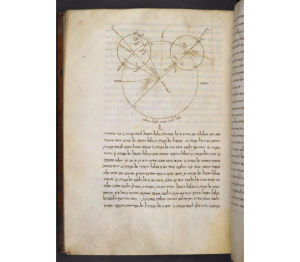

Next, I took a look at the internal content and what it could have said about the audience and the intended purpose of use. Once opened, the manuscript has a collection of mathematical illustrations of circles and other astronomical relations. The illustrations were in black, as well as the text, so one can confidently state that the visual aspects of were not extravagant. The illustrations and words were so mundane, I inferred that this manuscript was not made for the average person as there would be no entertaining pictures for them to look at (since most were illiterate). Instead this composition was made for a specific stature of persons, most likely a learned one. Not only is this manuscript for a specific class, but also for people of a specific religion. The entire text is in Hebrew suggesting that any literate man of Jewish faith would have had access to and observed proper use for it.

Lastly, I went deeper into knowing exactly who created this manuscript and possibly why he would have made it. The scholar was clearly well funded as the book was made of the best material which indicates that he was a man of noted caliber. Sure enough, the description underneath the digitalized manuscript describes Abraham Bar Hiyya as a famous astronomer, mathematician, and philosopher of the 14th century (British library, Polonsky foundation catalog) . It can be noted that his original works apparently had an exceptional impact on European science (British library, Polonsky foundation catalog). His history with the sciences was extensive and this particular manuscript was most likely another contribution to his academia portfolio. This manuscript would most likely be used for academic reference with intent to bridge a gap between the traditional Jewish calendar and widely followed Christian calendar.

Looking into the detail of this manuscript, it is clear that it held remarkable value. In its prime it was most likely referenced by all clergy and Rabbis alike in attempt to understand each other and establish some sort or order between their dates. Acknowledging the significance of the appearance and material in a manuscript as opposed to basing its worth solely from literary content, opened my eyes to the life of a medieval manuscript creator. The pages and ink took time, money, dedication, and precision. A manuscript stands as a great reference for us to look into the genuine customs of medieval people and this one proves that more than anything I have had the chance to observe. Just by looking at the literary content, one could confer that it was scientific. However, by understanding the effort put forth by Abraham Bar Hiyya, I was able to recognize its significance of use, means of production, and its overall more accurately observed grandeur.

Works Cited