By examining the materiality of a medieval manuscript, analyzing the material context of said document, one can learn quite a bit about its origin, its purpose, its usage, and, at a broader scale, the world in which it existed. Examining things like size, language, origin, owners, and other aspects of the physical form of the manuscript can provide insight into all sorts of things. Here, we’ll examine the British Library’s MS 26957, an Italian rite siddur, or Jewish prayer book. From this analysis, we will learn about various influences upon Jewish culture in the area as well as the state of said culture in general. This will give us greater historical insight into Jewish practices, and I will attempt to provide some context and comparisons to modern Jewish culture and practice, about which I know quite a bit.

That the size of this manuscript is fairly small, although not pocket-sized, suggests that it was made for personal use. Indeed, this is the case, for it was made by a relatively well-known scribe and artist, Joel ben Simeon Feibush, for patrons Menahem ben Samuel and his

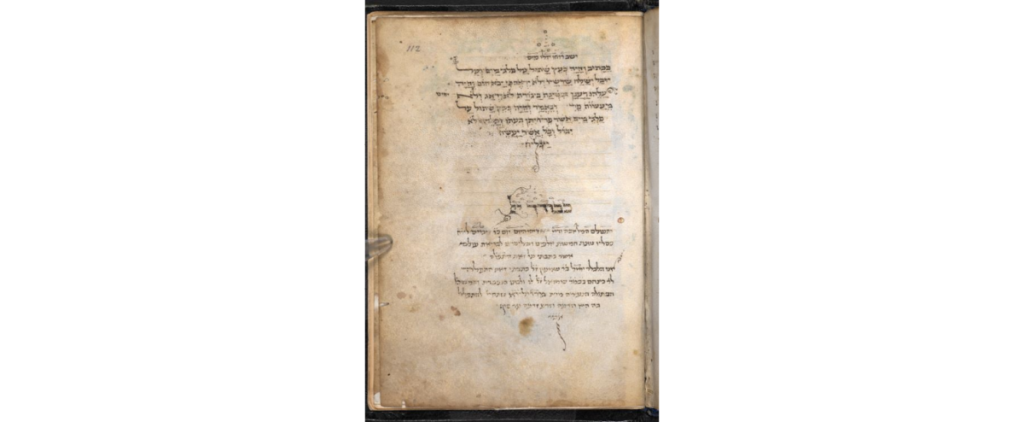

Supposedly contains information from the scribe on himself and the recipients (Cohen).

daughter Maraviglia. In the modern day, siddurim are generally kept in synagogues in a generic form, which people will take for their use solely within the synagogue. Many do have their own person siddur in their home, but in general do not carry it around. As this particular siddur dates to 1469, we can reason that this was far too soon after the creation of the printing press to be a possibility. Thus, the inference here is that, prior to common access to movable type and printing capabilities, it would be common for people to either have their own personal siddur or not use one at all. It’s unlikely most people could have all the prayers memorized, so the former is most likely. This means there were people dedicated to scribing such prayer books, since not everyone can make there own, which certainly makes sense; indeed, Feibush was one of them, for he made many prayer books and related works

This particular siddur seems to be an all-in-one prayer book. These days, there are generally different kinds of prayer books for different purposes: one for weekdays, one for the Sabbath and Festivals, one for specific holidays, one for High Holy Days, etc. This prayer book seems to have been made to cover all events (though the daily prayer segment has been ripped out). It is likely this isn’t the only example of such a phenomenon: In all likelihood, everyone had personal, all-purpose prayer books which they could carry to every service and ritual. This also means the scribes couldn’t be specialist: they needed to have enough general knowledge to be make sure to cover everything, though they likely were able to copy works already in existence.

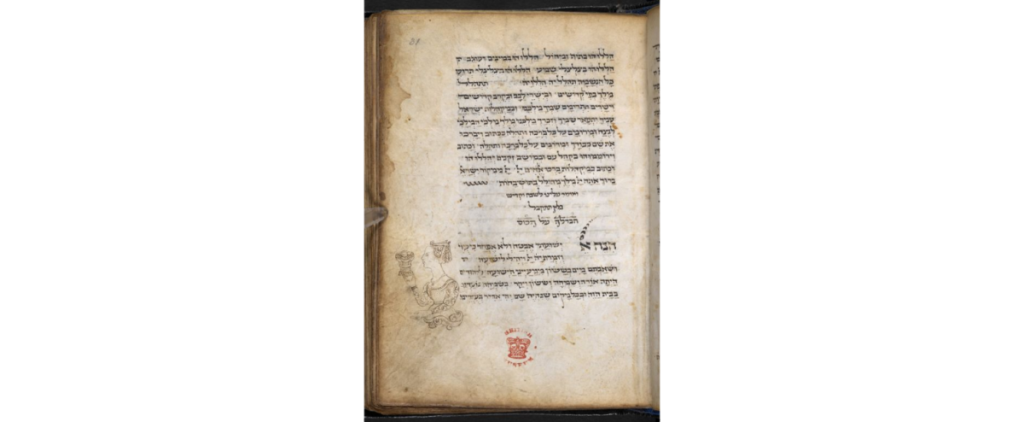

Let’s get more specific. According to most sources, this prayer book was indeed used primarily by Maraviglia, suggesting that, while they would be separated from the men, women still participated in religious services, in their own way. Illustrations throughout the book

Depicts a young woman reciting the Havdalah prayer over wine.

demonstrate various instances of women participating in Jewish rituals, which has already been covered Dr. Evelyn Cohen’s article on the subject and will not be covered extensively here, but suffice to say they do further affirm that Jewish women partook in ritual practice almost as much as men (Cohen). As this was Italian rite during the Renaissance period, it’s apparent that the Renaissance’s relative equality for women applied to all people, including Jews.

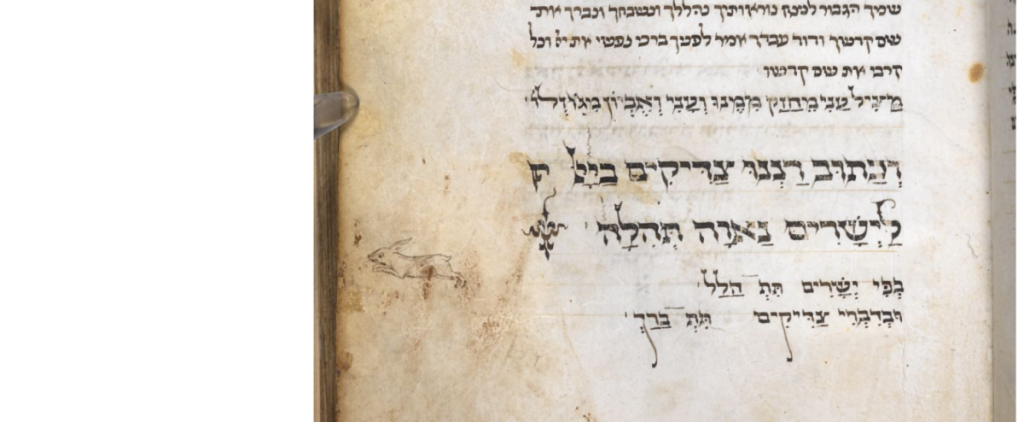

Depicts a rabbit hopping.

Additionally, there are various illustrations and drawings of creatures, both real and fictional, such as rabbits and dragons. While likely a stylistic choice, having illustrations of any kind in prayer books is uncommon in the modern day. It’s likely this was common for manuscripts at the time, perhaps even in Christian prayer books, and this may have spread to Judaism due to the general culture at the time.

Much of the text is smudged and the pages well-worn, suggesting the book saw its fair share of use. We can infer that this means that despite any cultural changes occurring at the time, religion was still an important aspect of Jewish people’s lives. That said, secular living was also of clear importance, due to all the general surrounding influences that have become apparent. It is possible this had some influence upon the Modern Orthodox movement that would arise several hundred years later.

While there’s still plenty we don’t know about Jewish practice and culture at this time from this source alone, we have gleaned quite a bit of insight into the practice at a personal, individual level.

All images from Add MS 26957.

Works Cited

Add MS 26957. 1469. The British Library. Accessed 15 Oct. 2017. http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_26957

Cohen, Evelyn. “The Illustrations in Maraviglia’s Prayer Book (Add MS 26957).” Published 7 Nov. 2016. The Polonsky Foundation Catalogue of Digitised Hebrew Manuscripts. The British Library. Accessed 15 Oct. 2017. https://www.bl.uk/hebrew-manuscripts/articles/the-illustrations-in-maraviglias-prayer-book