Studying any artifact gives a rewarding and fascinating look into past generations and clues current generations into the nuances of a life before our own. Handmade medieval manuscripts are among the most fascinating of preserved artifacts due to their multifaceted display of workmanship, creativity, and dedication. Nowadays, the way a book is printed has an much less significant impact on the way we perceive the meaning and purpose of that book, but before a medieval manuscript is even opened, there is a wealth of knowledge to be gained from the very pages, bindings, illuminations, and the structure of it. With so much of this era spent focusing on religious texts, I found the manuscript on medieval astronomy, Aberystwyth 735C, to be particularly fascinating. I thought that the inevitable religious impact on the science would make for a fascinating clash of beliefs. This interesting combination of Greek Phaenomena and early scientific observation, along with material clues into the physical creation of the manuscript, makes it into something much larger than it seems.

The physical manuscript is a combination of two parts. The first comes from the Limoges area of France in the eleventh century while the second comes from the same region but is dated about one hundred years later. While analyzing the materiality of this manuscript, one can see a dark brown leather binding encasing the text (Figure 1). “It was rebound in the early seventeenth century, probably in a London workshop, perhaps by the person whose initials, ‘T. M.’, appear in the blind-tooled decoration”. (National library of Wales). Nowadays, it is much more unlikely to do so, but in 1816, Richard Llwyd of the library of Plas Power, Denbighshire wrote inside of the front cover, “Astronomy and very curious”. After 1913, the manuscript was brought to the National Library where it remains today as the oldest medieval manuscript. The first and second part of the manuscript differ physically. The first seems to have existed as an unprotected folio due to the faded and more rough edges. This probably means that it was just carried around, possibly in a belt and could have suffered from natural damage. The ink used in the manuscript appears primarily in black, red, and green. ‘Royal’ and ‘fancy’ colors such as golds, purples, and blues do not appear very often in the manuscript, possibly showing that the production of this book was more quickly and cheaply produced.

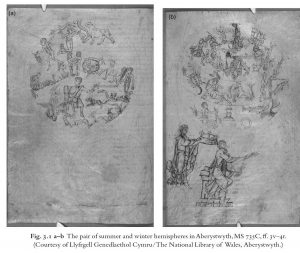

The main text of the first part of the manuscript contains a Latin account of the Greek Phaenomena by Aratus of Soli from around 300 BC. This work describes the constellations and a view of Earth from space through carefully detailed diagrams that create an interesting marriage of myth and science. For example, folio 4r. Features a winter hemisphere of Earth drawn with concentric circles with mythological creatures and humans clinging onto edges of those precise circles. (Figures 2 and 3). The dark sepia ink follows 43 lines with margins laid out by the scribe to detail where illustrations should appear. Many pages also contain verses describing scientific planetary motion and others feature zodiacal diagrams. The purpose of both the scientific and spiritual point of view on the stars may arise from the creators of this work wanting to point out how to both scholars and the literate how differently people view the world unknown to us; mostly what the earth might look like from space and in a much broader context. Compass holes also appear on the manuscript which point out how precise the scribes were with drawing what they thought to represent the solar system and constellations. The way text and image are combined in this manuscript is vital to its purpose. Many of the illustrations are used to detail how constellations are made up of spiritual creatures and humans in another life.

Observation of scientific discovery and Greek mythology leads to some interesting questions about the creation of this manuscript. It is noted by scholars of the National Library that this large collection of images seems to be unusual for a manuscript. The abundance of illustration and less text points to the scribes and authors of the manuscript compiling many different manuscripts in and around the area of Limoges, France to possibly explain constellations and other astrological questions. I believe this work was aimed at acknowledging many questions people may have had about the stars and the Earth as a whole. I believe this manuscript tried to answer those questions by piecing together scientific and mythological beliefs about what lies beyond the bounds of the Earth. Through its materiality, we see that this work must have been widely shared, beaten up, and seems to be a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’ of theories on the stars, pieces together by different materials and bindings.

“Royal MS 6 E IX.” Digitised Manuscripts. Web. 15 Oct. 2017. <http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Royal_MS_6_E_IX>.

Treharne, Elaine M. Medieval Literature: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford UP, 2015. Print.

“Medieval Astronomy.” Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales: Medieval Astronomy. Web. 15 Oct. 2017. <https://www.llgc.org.uk/en/discover/digital-gallery/manuscripts/the-middle-ages/medieval-astronomy/>.