Given the substantial resources required to produce a medieval manuscript, it would be insular to separate a text from the tangible materials that comprise the book itself. As Ann Gibbons of Science magazine points out, even the species of deerskin used to produce a leaf can tell a rich history of conquest, human migration, and socioeconomic change. The Sloane MS 1975 manuscript presents one such opportunity to examine materiality alongside the literature within. The bright inks, intricate illuminations, and ornate Protogothic script demonstrate Sloane 1975’s cosmopolitan character and real-world applications.

Produced in 1190 CE, Sloane 1975 is a Latin compilation of medicinal knowledge — the text draws from 4th Century works, including a treatise on herbs by Pseudo-Apuleius, a treatise on fauna-based treatments by Sextus Placitus of Papyra, and a second text on herbs by Pseudo-Dioscorides (Wellesley). Cursive text was also added in 1660 (British Library). The manuscript’s earliest known owner is the 14th Century Cistercian monastery of Ourscamp in Picardy, France. Sloane 1975’s exact place of origin, however, is not known. Scholars speculate that the text was made in Northern England or Northern France.

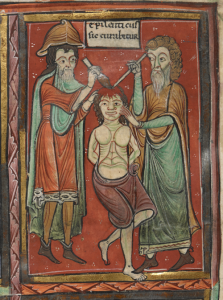

The manuscript’s illuminations are its most stunning feature. Painted in vermilion red, lapis lazuli blue, and rare green pigments, the decorations are a testament to the value of the manuscript (British Library). Like most contemporaneous works, Sloane 1975 uses fast-drying tempera inks (University of Minnesota). Gold detailing is also present. The scarcity of these inks — along with the costly price of vellum — lend an air of validity to the fantastical treatments described within. Sloane 1975 prescribes cannabis for swollen breasts, lauds the restorative properties of children’s urine, and instructs the reader on slaying a rabid dog (Wellesley). Nor do the illuminations shy away from gore, with bloodletting, hemorrhoid removal, and cataract removal procedures shown in graphic detail (Wellesley). These expensive, ornate images help affirm the legitimacy of the compilation and speak to its stature as an instructive text.

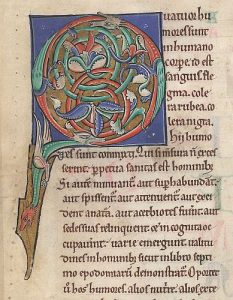

Another unique facet of Sloane 1975 is its historiated lettering. On almost every leaf — even those without illuminations — initials are brightly colored, separating one medical factoid from the next. One exquisite historiated “Q” portrays dragons and foliage, alluding to the mystique of knowledge in the codex. On many pages, the gridding for aligning text with images remains. The process of producing such a vibrant text was clearly a laborious task.

Sloane 1975 was likely designed to be a communal record of medical practice, belonging to a church that could afford such an elaborately illuminated volume. The codex is 30cm x 20cm, an imposing size characteristic of a display book.

Sloane 1975 is also a direct copy of another manuscript, Harley MS 1585, suggesting that these were curative methods meant to be shared (British Library). Indeed, the text’s monastic ownership would suggest as much; ecclesiastical institutions often served as repositories for knowledge (Treharne 26).

Perhaps the manuscript was brought out to instruct treatment for wealthy individuals who could afford access to literature and medical practitioners. As Treharne notes, religious institutions used manuscripts to build relationships with the upper class: “[Books] became showpieces for the religious establishments that made them…these may have been shown to wealthy patrons, or brought out on display in the church and shown to noble visitors” (25). In the case of Sloane 1975, the detailed illustrations suggest that the manuscript may have been designed to instruct actual medical practice, while also advancing the stature of the church.

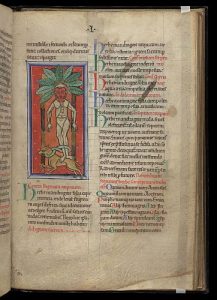

Many of the images demonstrate the properties of specific flora. The mandrake plant, for instance, was used to treat melancholy and mania (Wellesley). However, the plant had an intriguing place in folklore: “It was thought that the plant would scream when pulled from the earth and any who heard the screams would be condemned to death or damnation. Harvesting the plant would therefore pose some problems” (Wellesley). Fortunately, Sloane 1975 offers a picture-perfect solution. One illustration recommends tying the human-like mandrake plant to a running dog, allowing the roots to be harvested safely. Other images display a fearsome Venus flytrap and a fern sporting dragon-like claws.

Sloane 1975 was rebound five centuries after its creation with its current marbled cover. With its roots in the Middle East, the practice of paper marbling came into vogue in Europe during the 17th Century via trade routes (University of Washington). Although the manuscript’s original binding is lost, its current endpapers reflect an ample history of owners who sought to refurbish the historical work.

Much remains to be known about Sloane 1975 — its original production, ownership, and intended purpose. Nevertheless, an analysis of the text’s materiality alone allows us to elicit much about the manuscript’s past. Its authors draw from a wide range of inspirations, making this text a truly cosmopolitan work. The manuscript’s contents include knowledge from the Roman era, but its style and decorative elements remain unmistakably medieval.

Works Cited