Do you have to read a book to know a book? Manuscripts in the medieval ages are often written in complex archaic languages which needed to be interpreted to better understand the purpose of the text. However, there is so much more than what meets the eye. Understanding how manuscripts were made and the materials that form it can give us a larger insight into a manuscript’s past.

The manuscript Sloane MS 1975 was dated back to the late 12th century but fell into the ownership of Sir Hans Sloan in the 17th century. The manuscript is completely written in Latin, but thankfully through various expert translations, the manuscripts history could be traced back to several owners that trace the work to being in both Northern England and France (The British Library Board). However, can we understand the manuscript by just look at it?

Upon looking at the manuscript, you take notice to the different materials used in its making. The materials used and the size of the manuscript indicates that the manuscript was highly valued. The entire manuscript was created on vellum. Vellum or alternatively calf-skin was considered to be the most pristine and the most valued form of parchment available, because it was near flawless and the fine hairs made it a very desirable surface to write on. Consequently, the cost to produce such a material was immense that only a wealthy individual or a well-funded institution could afford. Additionally, the size of the manuscript measures up to 300 x 200 mm (about 12 x 8 in) and contained 104 folios, which meant the use of many sheets of vellum (The British Library Board). The final manuscript is generally a large manuscript and would not have moved around often. Because of this, it would suggest that the manuscript resided in a personal library or common library.

In the case of this manuscript, the final residence of this work was in the personal library of Sir Hans Sloan (The British Library Board). The manuscript was rebounded to a leather cover that contains the stamp of his personal library. Additionally, the leather binding is lined with marbled paper. During this time, marbled paper was considered a new form of art that had only previously existed in the Far and Near East, and it wasn’t until the 16th century that European countries began creating it (Under the Covers). The addition of this lining shows that the manuscript meant more than just a book with text. By how the manuscript was created, we can tell that the manuscript not only had an immense physical value, but there was also a great appreciation and respect for the content which it held.

The content of the manuscript is primarily a collection of descriptions and medicinal uses of various plants and animals. Going through the manuscript, I instantly associated this work to a medieval textbook. The way the manuscript has been organized shows that it was intended for informational or educational purposes. For example, the presence of a “table of contents” in the preface might have been used to quickly access certain topics outlined in the manuscript. Additionally, the ends of the manuscript contain blank pages of vellum. However, not all of the pages are blank. Some, especially those at the end, contain handwriting that closely resembles someone taking notes. Having these pages at the end could’ve been a way for notes to be stored, which emphasize its purpose as more of an instructional and informative text.

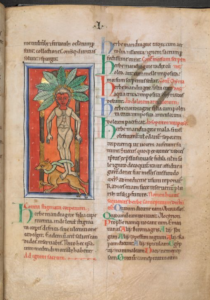

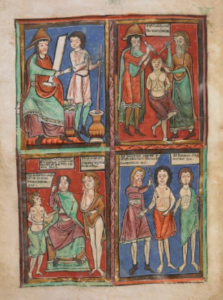

Continuing through, you will notice there are numerous illuminations throughout the manuscript. These were not just a decorative embellishment, but a utilized visual aid to assist in the description and the differentiation of the many plant and animal species. Not all, but many of the illuminations are somewhat of a metaphorical depiction. For example, the mandrake is drawn as a human with a plant head. This was because many mandrakes commonly split at the end and form the structure of a miniature human. Alternatively, many depictions are much more vivid. Illuminations near the end portray scenarios in which certain procedures are conducted on humans. The illuminations provided a way to visually learn the text and serves to better inform the reader. By how the manuscript’s content was composed, there was a high likely hood that the manuscript was intended to be read by an educated person with a strong interest in learning this particular subject matter.

It is, of course, not entirely possible to fully understand the text by just looking at the book. However, with basic knowledge about how the manuscript was made and the certain details within it, it can strongly be inferred that this text was a used to better understand animals and plants and what they are used for. Sloane MS 1975 was a manuscript intended for a highly educated person, and with the current the social status at this time, those with an education were those who were apart of the wealthy. So, do you have to read a book to know a book? You definitely can!

References

“Marbled Endpapers.” Under the Covers – The Hidden Art of Endpapers, salemathenaeum.net/endpapers/photos.html.

“Snakes, Mandrakes and Centaurs: Medieval Herbal Now Online.” Medieval manuscripts blog, blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2016/09/snakes-mandrakes-and-centaurs.html.

“Sloane MS 1975.” Digitised Manuscripts, www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Sloane_MS_1975.