Moral Agency on the Streets: A Revolution of Love

Set a table, invite everyone to come. Don’t turn nobody out, no matter where they’re from. Build a house on every vacant lot. We ain’t too proud to beg, when we’re giving everything we’ve got. We’re talking about a revolution, a revolution of love. -“Revolution,” Mercy Community Church Worship Song

Life on the streets of Atlanta can be a dangerous, difficult, and often lonely experience. It involves a complex web of internal and external factors that inhibit people’s choices and ultimately their ability to thrive. However, despite the many constraints placed upon them, our neighbors on the streets exhibit daily acts of moral agency that show their creativity, resilience, and human dignity. In this post I will first look at some of the specific constraints of life on the streets in Atlanta. Next, I will offer a specific example of how one community of those living on the streets expresses moral agency through worship and song. It is my hope that this model may serve as a helpful example for anyone interested in why thinking about moral agency under constraint matters.

Those Living on the Streets as Moral Agents Under Constraint

Let me start by explaining why life on the streets of Atlanta should be considered a context of constraint. Think about all the functions that a home serves. It provides shelter from the elements (cold, heat, storms, floods, ice, etc.). It is a place where you can store your possessions or keep things safe (like a birth certificate). Home is where you can get a good night of rest with the lights turned off, where you can recover from an illness, or sit down for a while after a long day of working. Home is where you can use the bathroom, bathe yourself and your children, wash your clothing, clean a wound. Having a home offers social status. It is a place where you can meet your friends, or relax and be yourself. Without a home, one is subject to all the dangers and limitations that housing avoids, from the extreme physical dangers of hypothermia and exhaustion to the subtler limitations of having nowhere to charge your phone or have a moment of privacy.[1]

Though it is a common goal of those living on the streets, getting into shelter does not always make things easier. While it may solve some problems (risk of hypothermia), it can often offer its own set of obstacles. Available work is not often located near shelters. Shelter curfews do not align with work schedules. Public transportation in Atlanta is limited, costly, and time consuming. Some shelters have strict regulations on who can be admitted and on what terms. Even if you can get a night in an emergency shelter, you may have to sleep on some mats on a tile floor huddled with your kids and forty other women. Even if you can get indoors on a night when the temperatures drop below freezing, you may get kicked out as early as four in the morning when temperatures are at their lowest. [2]

Other constraints of those living on the streets include the negative assumptions many people possess about homelessness and those experiencing it. Political philosopher Martha Nussbaum describes how real compassion requires a belief of nonfault. She argues that “we typically don’t feel compassion if we think the person’s predicament chosen or self-inflicted.”[3] Thus, pervading myths that “anyone” with enough gumption can work themselves out of homelessness, allow people to convince themselves that those living on the streets are at fault for their predicament, and thus do not deserve compassion, respect, or relationship.

The next time you are tempted to entertain the argument “why don’t they just get a job,” you may consider just how difficult that task may be when you do not have some place to go home to and shower first, when you do not have a safe place to store your identification, or you do not have reliable transportation.

The aforementioned constraints are merely some of the factors affecting those living on the streets of Atlanta. Sociologist Christopher Jencks suggests that there are many reasons that contribute to a person’s likelihood to end up and stay on the streets, including whether or not a person has valued job skills, claims to government benefits, struggles with addiction or mental health, or has ties to family or friends willing to help.[4] Other problems facing those who live on the streets include but are not limited to: family violence, disabilities or chronic medical conditions, and criminal records.[5] While not every person on the streets suffers from the same conditions, one’s individual constraints are compounded by the social isolation and lack of communal support experienced by many of those who live on the streets.

In naming these many constraining factors, I do not want to imply that those living on the streets are helpless or without agency, but merely to suggest that this population is often operating under many circumstances beyond their immediate control. The constraints endured by those living on the streets do not define their personhood, and can at times inspire individuals to overcome insurmountable odds. Whether or not such acts are those of mere survival or outright resistance, these choices constitute acts of moral agency that speak to the humanity and dignity of those enduring under the constraints of life on the streets. Before examining a specific example of moral agency on the streets, let’s consider a working definition of moral agency.

A Working Definition of Moral Agency

Many classic definitions of moral agency have focused on one’s ability to determine between “right and wrong” or “good and bad.” These limiting dualistic categories assume that such concepts are universal and can be reasoned objectively, discounting the complicated situations within which actual human beings find themselves (like life on the streets). Moreover, definitions of moral agency have often served the purpose of determining whether or not a person should be held accountable (i.e. whether or not they are punishable) for their actions, again giving little precedence to the context within which such actions have occurred. From culture and upbringing to the effects of immediate situations, maybe all choices are shaped by individual past and present contexts.

However, even within complex situations involving layers of factors beyond human control, humans continue to make choices and act for the benefit of themselves and others. In Homeless Families, Barry J. Seltser and Donald E. Miller write “the most important condition of dignity is an appropriate degree of autonomy. Human beings require a sphere of choice, a sphere of action over which they have some control and discretion….to severely restrict our choices is to threaten our human dignity.”[6] The choices of those living on the streets of Atlanta are often severely restricted by the multitude of layered constraints placed upon them, however, to ignore their acts of agency is to further deny this population their human dignity. Even under many constraints, these real people are making daily choices that affect their lives and situations. To see this is to see those living on the streets for their human dignity.

A way of describing acts of moral agency might be to consider those acts which acknowledge the humanity of oneself or others through choices. While maybe no act comes without a context of constraint, the ability to have some role in one’s choices (even if it is merely the choice of what attitude one takes concerning unavoidable situations) is linked to the acknowledgement of human dignity and thus moral agency.

Wherever on the spectrum of “more good” or “more bad” our choices may fall, it is those that acknowledge one’s own human ability to make some level of choice that constitute acts of moral agency. People living on the streets of Atlanta make choices that help them to survive as well as protest a broken system. These acts of moral agency serve as a reminder that at the heart of the complicated and often seemingly helpless “problem of homelessness” are real individual people working hard, offering solutions, enduring, and participating in acts of moral agency that offer dignity and honor their humanity.

A Community Church Songbook as an Exercise in Moral Agency

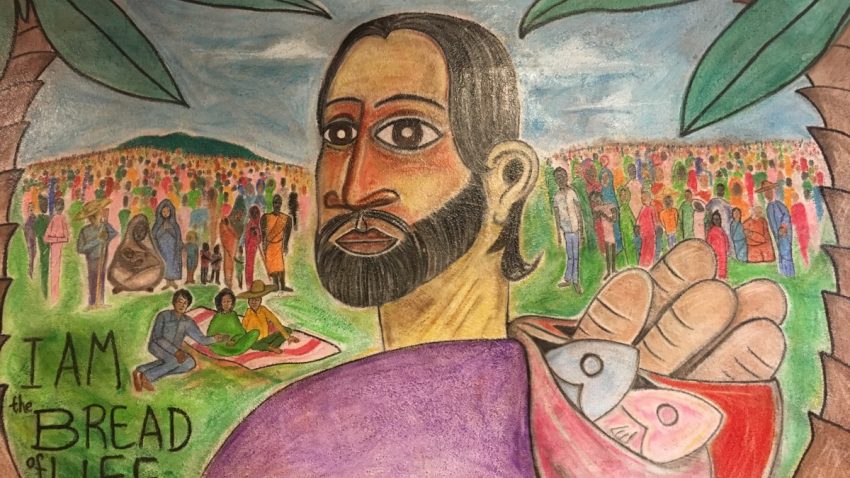

One example that serves as a model for the creative and resilient use of moral agency on the streets is found in the songbook of Mercy Community Church. “Mercy” is a small worshiping community consisting mostly of people who live on the streets of Atlanta. Mercy is a place where on a Sunday morning those living on the streets can feel welcome to come indoors, drink coffee, make music, listen to readings, argue scripture, and share in communion.

Like most Christian churches, the members of the Mercy Community use songs as a part of their worship services. Though they do not have bound hymnbooks, they have a small stock of multi-colored folders with “Mercy Songbook” written across the cover in black permanent marker. Within these songbooks are printed copies of songs including some old hymns, traditional black gospel, and many songs in Spanish. Among this very intentional selection of relevant worship songs are many songs written specifically for and by members of the Mercy community.

Two songs I would like to highlight in particular are “Revolution,” written by the church’s pastor, and “Cool Like That,” written by a former (now deceased) member of the community. One verse of “Revolution” reads “set a table, invite everyone to come, don’t turn nobody out, no matter where they’re from. Build a house on every vacant lot, we ain’t too proud to beg when we’re giving everything we’ve got.” The chorus goes on to state “we’re talking about a revolution, yeah, a revolution of love.” This song utilizes familiar Christian imagery such as an open table, but also includes other powerful images relating specifically to life on the streets. Along with depicting a meal to which everyone is invited to partake, this song envisions a city in which vacant lots become accessible housing for all, and humans do not feel shame in asking for the things they need to live. The song states how such a vision would be “a revolution of love,” an overthrow of the current situation wherein humans do not always receive the food and shelter they require, and “homelessness” is associated with shame, fear, and moral failing.

Another song in the Mercy songbook is called “Cool Like That.” This song also addresses some of the specific daily activities of the Mercy community, while using irony and humor to associate such tasks with “coolness.” The song opens with “lunch-time’s over, it’s clean up time, we’ve gotta wash those pots and pans, and make them shine, because we’re cool like that…” Another line reads “we’re out on catch-out corner with the poor, we got the kind of love you can’t buy in no store, because we’re cool like that…” The song’s final verse states “you want a revolution, here’s what to do: respect your sister and your brother too, and you’ll be cool like that.” Similar to “Revolution,” this song envisions the “revolutionary” practice of choosing to respect and honor human dignity.

Within the context of life on the streets, these songs are examples of moral agency in how they express individuals’ assertions of their own human dignity and everyday resistance to the constraints placed upon them. In “Revolution,” the line which states “we ain’t too proud to beg, when we’re giving everything we’ve got,” is a bold demand to be taken seriously as a person. Saying that one is not “too proud” to do something is a way of claiming ownership and even honor in that action. It turns the stereotypical image of the meek and needy homeless person on its head, asserting instead that those living on the streets are active agents forging their own futures. While they “ain’t too proud,” they demand the respect that any human deserves. It is also significant that this demand for respect is called a “revolution of love.” In A Feminist Ethic of Risk, Sharon D. Welch speaks to how love can energize sustainable works toward justice far better than guilt, duty, or self-sacrifice. Loving someone requires the hard work of actually seeing and knowing them for all their humanity. It bestows human dignity. [7] In asking for a “revolution of love,” this song not only demands the overthrow of broken systems (a revolution), but that such work be done with love, so that those hurt by such systems would be seen for their humanity and loved.

In “Cool Like That” more assumptions about the drudgery and helplessness of homelessness are contradicted. In this song, “coolness,” something often associated with power, money, and wealth, is instead paired with the tasks of cleaning dishes, hanging out with day-laborers, and serving a meal on the streets. This song too, pushes against the societal standards of “coolness,” and instead makes the provocative declaration that what makes someone “cool” is ultimately their ability to show decency and respect to their fellow human beings, even (and especially) those marginalized by life on the streets. These songs depict those living on the streets not as agentless byproducts of a broken economic system, but as full human beings who can choose to actively protest and resist the limitations of their constraints.

While these songs highlight how protest serves as a form of moral agency for those living on the streets, I do not want to make the claim that intentional protest is a requisite of agency. In a case study looking at the everyday resistance of the Madres de Desparecidos in Argentina, theologian Keri Day states that “hope and moral imagination emerge at the site of ordinary and everyday lived experience…these women embodied a moral imagination about future possibilities that were grounded in the social worlds they already inhabited.”[8] While the Madres participate in an intentional act of protest that is “grounded in their current social world,” I would argue that hope and moral imagination emerge even in everyday choices that are not intentional forms of dissent. The song “Cool Like That,” notes that even the choice to help clean up dishes is an enacted moral choice that people within this community make. One’s choice to help clean dishes after a shared meal may not be undergirded by the larger implications of the broken systems this meal protests, however, this personal choice to wash dishes does help maintain a community practice that results in human bodies being fed. Making the choice to participate in an activity that cares for one’s own physical needs and the needs of others is a small, but important, example of a choice that acknowledges one’s own (and others’) human dignity. While the choice here may be simply one of survival, it is still a choice that results in care for individuals, and thus “hopes and imagines” for a future in which it is common sense that all humans would receive the sustenance they need to live.[9] Intentionally or not, these simple acts do embody a moral imagination that protests against those who would fail to see these individuals for their humanity. Even if the woman eating a piece of donated bread and then passing a second piece along to her friend is not currently in a mindset to imagine a better world, in that moment of taking the time to nourish herself she embodies a belief that she is worth being cared for and that her life is worth living. She makes a moral choice to care for herself and another, ultimately expressing agency and acknowledging her own humanity and that of another.

What This Moral of Agency Can Teach Us

Mercy’s worship songs serve as a sort of double example of moral agency. Not only is the act of coming together to sing such songs of protest a form of moral agency, but the simple scenarios depicted in the songs’ lyrics describe other daily acts of moral agency on the streets. While Mercy’s worship songbook defines how a specific community exerts moral agency under constraint, this example has something to say for how we think about these often obscure concepts and why they matter. In this model the simple acts of gathering, singing, eating, and sharing constitute acts of moral agency, because they involve choices that honor human dignity and life. In this city those living on the streets are often dehumanized. The “issue of homelessness” is frequently mentioned as an eye-sore to downtown building projects or concerns for public safety. Yet, this “issue” involves real people living in our city. Thus, any time these people gather for worship or a meal they make a morally charged decision to assert their humanity, their right to have their human bodies fed and protected. Within a situation with very limited choices, they choose to perform acts of protest and survival, asserting that they too are humans worthy of relationship, acknowledgement, and love. This model is helpful in that it looks at moral agency within the spectrum of our often limited choices, that can still in some way or another acknowledge our humanity in powerful ways. Are choices of survival moral choices? Yes, because they are choices that preserve human life and thus honor human dignity. Moreover, this model speaks to the importance of relationality in the moral choices we make. These songs not only speak to the moral decisions of preserving and honoring one’s own life, but also of the simple choices that acknowledge others’ human dignity as well. In a world of limited choices, hoarded resources, and dehumanizing “issues,” it is important to remember that we are all humans and we all have a right to someplace we can call home. When making choices, remembering one’s own humanity as well as the humanity of those whom those choices affect may be an important place to start. In this example of moral agency under constraint, we are reminded that choices, both big and small, intentionally or not, can have the power to protest broken systems, honor human dignity, and plant powerful seeds for revolutions of love.

Many of those living on the streets in our city have been deeply impacted by the Covid19 crisis. Places of refuge (from church shelters to libraries) have closed. Access to resources (from ministries to the DMV) have been temporarily unavailable. Panhandling for change or a meal has become difficult to sustain. Some early efforts by the city helped a limited number of people with pre-existing medical conditions into housing, but many more vulnerable people remain without safe places to “stay home” and shelter. Throughout this crisis, the Mercy community has never stopped gathering to share food and resources, pray with another, share vital information, and be a community of support. The community has made many adaptations to keep one another safe (including meeting out of doors in the shade, practicing distancing, and wearing masks), but they have never stopped offering the gift of presence and fellowship to one another. The community continues to grow in numbers each day as more people attend the outdoor gatherings seeking resources, hospitality, and moments of refuge and respite.

Footnotes

[1] Rene I. Jahiel, Homelessness: A Prevention-oriented Approach, (Baltimore, MA: The John Hopkins University Press, 1992), 5.

[2] Steven Bouma-Prediger and Brian J. Walsh, Beyond Homelessness: Christian Faith in a Culture of Displacement, (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2008), 102-103.

[3] Martha C. Nussbaum, Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice, (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013), 143.

[4]Christopher Jencks, The Homeless, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 49.

[5] Georgia Department of Community Affairs, “2015 Report on Homelessness: Georgia’s 14,000.” Accessed September 26, 2017, http://www.dca.state.ga.us/housing/specialneeds/programs/documents/HomelessnessReport2015.pdf.

[6] Barry Jay Seltser and Donald E. Miller, Homeless Families: The Struggle for Dignity (Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 98.

[7] Sharon D. Welch, A Feminist Ethic of Risk, (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2000), 162.

[8] Keri Day, Religious Resistance to Neoliberalism: Womanist and Black Feminist Perspectives, (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 159.

[9] Ibid.

Thank you Brittany for this amazing and thorough article on Moral Agency. I always look forward to anything you write. I’m hoping this and future information is available to many.