East Atlanta is home to some of the metro area’s oldest suburbs. From the picturesque estates of Druid Hills to the hardy old and newly-constructed craftsmen bungalows of East Lake, these communities have histories spanning over a century. On a quick drive through many of these neighborhoods, you cannot help but notice how various iterations of Black Lives Matter signs freckle the front-yards. While all of these communities were historically white, some of them (e.g., East Lake, Kirkwood, Oakhurst, et al.) became predominately black between the 1960-80s[i]. In the last 20 years, however, gentrification and redevelopment have ushered white people back into these communities. While one cannot say for sure, barring interviews at every property, that only white households are wielding Black Lives Matter signs, it has been my direct observation that many of the families and institutions displaying a Black Lives Matter sign are white. To state the matter plainly and clearly – white people in affluent and upper-middle-class neighborhoods have Black Lives Matter Signs in their front yards and windows.

Figure 1 Home in East Atlanta Village with two Black Lives Matter signs

On the surface, the proliferation of Black Lives Matter signs in predominately or increasingly white neighborhoods reads as a definite positive, especially if it is white folks who are placing the signs on their property. This project, however, aims to reveal the limits of moral agency under constraint and show how moral agency can empower its constraint. Here is the argument in three parts:

- White people planting Black Lives Matter signs in their yards is a form of anti-racist praxis and thus a form of moral agency.

- Anti-racist praxis is constrained by whiteness.

- This form of moral agency effects hegemonic whiteness.

Black Lives Matter: A Brief History

Following the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012, and the acquittal of his killer, George Zimmerman, in 2013, three black women, Alicia Garza, Opel Tometi, and Patrisse Cullers, inaugurated #BlackLivesMatter. This hashtag, moniker, proclamation even emerged as a “response to the anti-Black racism that permeates our society” (Garza 2014). Recognizing how black bodies are “systemically and intentionally targeted for demise,” Garza, Tometi, and Cullers offered an “ideological and political intervention” that would target state-sanction violence and vigilante violence threatening and snuffing Black lives. As a decentralized movement galvanized mostly through creative uses of social media, #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) galvanized black and brown millennials for social change. Tapping into the legacy of 1960’s Civil Rights Movement’s direct action and civil disobedience approach, BLM organizers planned actions chiefly aimed to disrupt business as usual, politics as usual, and mass media as usual. Critical theorist Charles Linscott describes the movement as working through and by “insurrectionary street action and the viral media exposure of disruptive praxis” (Linscott, 2017, 114). From shutting down interstates with human chains to staging die-ins in churches, malls, city halls, airports, and schools, BLM activists engage in forms of protest that disrupt the normativity of public spaces, even white ones. Of particular note are the ways black women, queer, young, and poor people served as leaders and organizers of these actions. Recognizing and acknowledging the ways hetero-patriarchy undergird anti-black practices, policies, and structures, Garza says: [BLM] affirms the lives of Black queer and trans folks, disabled folks, Black-undocumented folks, folks with records, women and all Black lives along the gender spectrum. It centers those that have been marginalized within Black liberation movements (2014).

As an anti-racist movement, Black Lives Matter concerned itself, in its direct actions, protests, and other forms of resistance with two things. Externally, the aim was not merely equality and fairness for blacks, but to expose and disrupt the state’s structural anti-black orientation. Secondly, internally, the goal was to affirm the diverse manifestations of black life as echoed in the quote above. Linscott notes the movement’s affirmation that, “black life must take precedence over both capital and anti-black violence (state-sanctioned and otherwise)” (109). Recognizing poverty, incarceration, and the hyper-sexualization and criminalization of Black people as forms of state violence against blacks, the movement sought to make clear the effects of white supremacy across the full spectrum of Black life.

While vision and leadership for BLM were cast by a diverse set of Black players, white people were not excluded from participation or even leadership. Garza notes that the work is not just for black people but also for whites. Garza notes that allies and those who stand in solidarity with the movement must do so taking note of the ways they participate, are complicit with anti-Black racism and “investigate how anti-Black racism is perpetuated in [their] communities” (2014). It is important to note that Garza is calling for two critical forms of praxis for allies, white or otherwise. First, there must be some form of agreement that Black lives do in fact matter. Secondly, one must reflect on how one’s own community is complicit with anti-black racism. To do these two things, per Garza, is to be a good ally.

Of Signs, Anti-Racist Praxis, and Moral Agency

Signage, along with music, drumming, chanting, and choreographed movements played an important role in Black Lives Matter protests and direct actions. From #Solidaritrees[ii] In Washington DC to “Fuck the Police” banners in Oakland, signs functioned as a visual means of voice rupturing cityscape and commanding attention. The hashtag that had taken social media by storm stretched from digital space to physical space in the form of buttons, pins, t-shirts, and yard signs. All of these items are readily available for purchase now online from private vendors to major retailers like Amazon. Whether by purchase or by making one’s own sign, to possess a Black Lives Matter sign is to act affirmatively.

Put differently, Black Lives Matter signs are not like address plaques or porch lights – traditional exterior home fixtures. Their presence is intentional and by choice. In this way, the presence of the sign disrupts the normal and perhaps familiar visual field of the property. That the statement is itself a declaration affirms some level of intention, belief, and/or conviction of the user. Given that the movement’s moniker is a declaration, users have a variety of ways to understand their solidarity. For some, the sign can function as an affirmative statement, while for others it can be their way of affirming the movement and the means by which the movement propagates its message. For other still, it can be an affirmation among many, with the purpose of declaring a comprehensive set of beliefs. Regardless of the user’s intentions and motivations – the presence of the sign itself is a form of solidarity with at least the idea that it needs to be stated, affirmed, and made explicit that Black lives do matter. Additionally, the use of the sign shows recognition that such a statement is only necessary because there are actions and events taking place that indicate Black lives do not matter.

Anti-racism is the active process of identifying, challenging, and changing the values, structures, and behaviors that perpetuate individual and systemic racism.[iii]

This two-fold recognition is the foundation for how using a sign can be understood as a form of anti-racist praxis. Users, in some way or fashion, recognize that black life is precarious given the current social and political reality and instead of being silent and saying nothing, challenge the normative anti-black orientation by affirming that Black lives do matter. This affirmation is visible and accessible to the broader public. It is the declaration of a value that they share and would want others to share. In a Kantian framing, the usage of a Black Lives Matter sign can be understood as a categorical imperative – as it would be an acceptable practice for all people to agree affirmatively that Black lives matter. While it would be unreasonable to expect that a sign would change policy and structural societal issues, it is more likely that the sign communicates a set of values that intend the wellbeing and affirmation of Black life. The usage of the sign proclaims an individual value in response to actions, beliefs, and/or practices the user finds problematic, unjust, unfair, uncaring, and/or inhumane.

Moral agency manifests as the actions, habits, and/or practices consistent with the agent’s moral commitments as she encounters a moral problem or opportunity.

As it pertains to anti-racist praxis, moral agency manifests as a response to the issue of racism. When a moral agent recognizes racism at work, any action that seeks to undermine that racism can be understood as a form of moral agency. As the word anti-racism intones, the overarching constraint is racism. Homeowners in these predominately white communities choosing to use Black Lives Matters yard signs are doing so in light of their framing of the moral problem. Additionally, it is their framing of the issue that informs what they see as possible solutions or forms of moral praxis. As homeowners recognize racial privilege and inequality and black oppression, their desire to stand for equality and fairness could readily be intoned by placing a Black Lives Matter sign in their yard. This sentiment is strengthened when one acknowledges the other kinds of yard signs that are present in these communities – signs that welcome foreigners, members of the LGBTQ community, undocumented residents, and Muslims. As part of a broader sociopolitical discourse on inclusion, multiculturalism, and diversity, Black Lives Matter yard signs can voice the owner’s desire for justice, equity, fairness, and peace. With these social values and political virtues shaping both owners’ understanding of the moral problem and their response, it is very well possible for other forms of ethical framing to be foregrounded.

This construction of moral agency favors a deontological framework whereby the moral agent’s fundamental commitments, her values even, dictate her actions. This values-driven approach does not centralize the outcome or the effect of one’s actions. Instead, it focuses on the sense of duty that governs how the moral agent shows up in the world. Anti-racism as moral agency conceived like this focuses on attitudes and beliefs and an individual’s core convictions and values. The critical thing to recognize about this form of moral agency is the extent to which the moral agent acts in concert with her beliefs. The effectiveness of her actions or what her actions effect is not the chief focus of this form moral agency. What the agent believes to be right takes precedence.

‘We Believe’ signs are among the most popular Black Lives Matters signs throughout East Atlanta.

Local Baptist Church with Black Lives Matter Sign

East Atlanta newer build with Black Lives matter sign

Oakhurst Presbyterian Church with two Black Lives Matter signs

We Believe sign in East Atlanta neighborhood

Black Lives Matter sign in East Atlanta bungalow

New construction in East Atlanta Village

House adjacent to the new construction

The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is present in all we do. It could scarcely be otherwise since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, identities, and aspirations. And it is with great pain and terror one begins to realize this. In great pain and terror one begins to assess the history which has placed one where one is and formed one’s point of view.

–James Baldwin “White Man’s Guilt”

Racism, Whiteness, and the limits of Anti-Racism

To explore the relationship between racism and whiteness, let us turn our attention back to the East Atlanta neighborhoods that house our moral agents. When the East Atlanta neighborhoods were conceived in the 19th and 20th centuries, they had one thing in mind for black people – exclusion. Visual markers delimiting public and private space, during the post-Reconstructionist and Jim Crow eras made clear what areas were exclusively for whites. White spaces were often more auspicious and comfortable and valuable while black space intoned inferiority and undesirability. Organizing space and determining who had what kind of access to said space was vital in affirming and reinscribing the social order, a racist hierarchy. Residential space, in particular, was, and still is today, an essential site for racial segregation.

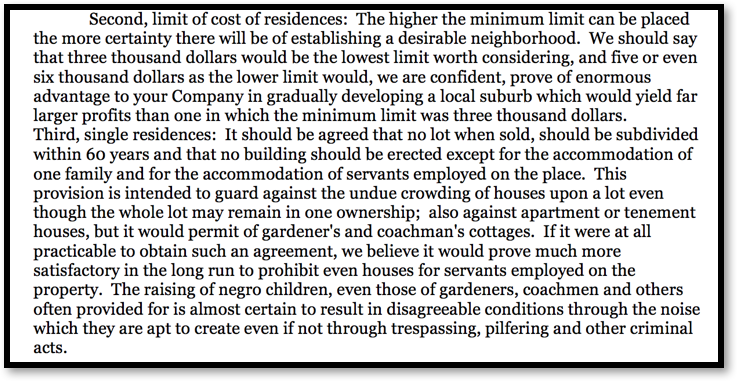

Original documents between the land developer for the Druid Hills neighborhood and the owner readily noted how profits and property values required exclusivity and desirability – whiteness. Affluence and prestige were normalized as white characteristics, and undesirability and adverse risk were explicitly associated with blackness. The picture below is from a1902 correspondence regarding deed restrictions from the Olmsted firm to the Kirkwood Land Trust.

Figure 3 – 1902 Correspondence from the Olmsted Firm to the Kirkwood Land Trust (Druid Hills, nd).

This document makes clear the connections between class, desirability, white exclusivity, and black inferiority. Blackness, as it pertains to the construction of this community, is, from the outset, understood as disagreeable, noisy, and ultimately criminal. Blackness is a threat to the very ethos of a community intended to affirm white flourishing and propriety. White lives matter. Comfort, beauty, safety and money were understood to be the highest ideals attainable only through white exclusivity. While this document is specific to the Druid Hills neighborhood, its priorities and presuppositions were and are not.

In an 1890 correspondence between the developer and the landowners the following was communicated:

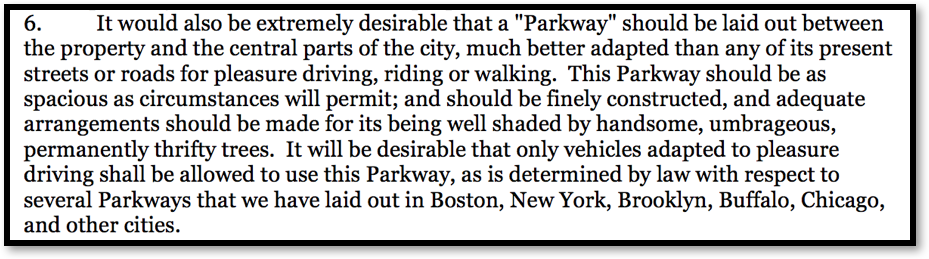

Figure 4 denotes an 1890 communication between the Olmsted Firm and the Kirkwood Land Trust (Druid Hills, nd)

Even the construction of roadways functioned to ensure pleasure reinscribe the sanctity of white wealth and tastes. The more exclusive the neighborhood, the more desirable residents it would attract, the more desirable the residents, the more profitable the endeavor, the more profitable the endeavor, the more whiteness is affirmed as superior. In the case of Druid Hills, we are not only witnessing the construction of a neighborhood but the structural power of whiteness to ground structural racism. The community was literally constructed to exclude black life while simultaneously making every provision possible for the expansion and pleasure of white life. Developers for Druid Hills constructed whiteness using privacy, shade, beauty, exclusivity, desirability, leisure, pleasure, and strategic protection. Whiteness here is not just about the color of one’s skin, but it is about being oriented and situated in the world of one’s own making. Racism ensures that there will be profits available for all the white parties invested. Historically speaking racism and whiteness go hand in hand in the making and success of a community like Druid Hills.

Other communities did not intone the same kind of white upper-class exclusivity of Druid Hills but still have their own problematic histories. East Lake was initially a plantation that was reconfigured as a vacation and recreational haven for white Atlantans. During the 1960s and 1970s, the racial make-up of some of these east Atlanta neighborhoods, like East Lake, changed from white to Black. Georgia State University scholars Lesley Reid and Robert Adelman have noted how “real-estate agents used white anxieties about having black neighbors to blockbust. They convinced white families to sell their homes at below-market prices and then reselling these same homes to black families at prime market prices, pocketing the profits” (Reid and Adelman, 2003). These patterns of racial segregation again hold at their center white exclusivity, white profits, and black inferiority.

In the last 20 years, however, gentrification has changed the make-up of these neighborhoods again, by displacing poorer and older black and brown people and making space for middle and upper-middle class white families. This new diversity with white families returning to many of these east Atlanta neighborhoods is now a selling point. Oddly enough, the communities are diverse, not because black people have recently moved in, but because white people have recently moved back.

The effects of this gentrification are not only economic development and revitalization, but also the creation of neighborhood institutions. The neighborhood associations’ security patrols are institutionalized makers of white gentrification and white reclamation of residential space. Their goal is the best interest of the community and property owners. The increase in property values and new housing stock make it nearly impossible for the older and poorer black residents who lived in the neighborhood as they declined to benefit from the new good fortune. They cannot afford the major renovations that increase property values, and when they do sell, their homes are likely to be torn down and new more luxurious one’s built in their stead. The rub here is not that the neighborhood associations are directly or explicitly anti-black, as was the case when the communities were initially constructed, but that the institutional values for maintaining property values, comfort for white residents, and normalizing white interests goes unchecked. Even as these communities teach and welcome diversity, the institutions they create effect the same expansive whiteness as their progenitors did.

While these neighborhoods are not explicitly anti-black, their reliance on the institutional and structural bodies intones the historical anti-black orientation – even as diversity and welcome are readily a part of these organizations’ discourses. It is the relationship between white property owners and their desire to make and keep their neighborhood pristine, housing values up, and maintain the perception of safety that guides the historical and present ethos of these communities writ large. Meanwhile, Black Lives Matter yard signs appeal to justice as a visual anti-racists praxis while leaving unquestioned the subtle and complex machinations of whiteness and white supremacy.

Nowhere is this paradox clearer than in the proliferation of neighborhood safety and security patrols. In Druid Hills, East Lake, Oakhurst, and Kirkwood, residents can opt to pay a yearly fee to support the neighborhood safety patrol[iv]. These organized efforts boast that off-duty police officers are paid to patrol these neighborhoods in uniform and carry weapons. Because they are police, they have direct access to the 911 switchboards and can arrest people even while they are not on the clock with their primary employer. Residents in these communities pay for additional policing to ensure that their neighborhood is safe. Here, class and whiteness work together to create and support favorable relationships with law enforcement. This is a fundamentally different usage of experience with law enforcement than what Black Lives Matters activists and black victims of police violence encounter.

In these communities, the very Stand Your Ground laws that made it possible for George Zimmerman to kill Trayvon are at work. Even as Black Lives Matter signs are present and dispersed throughout the community, one wonders if the white allies and sympathizers recognize a moral concern or contradiction. The same structures that are used to uphold the value and decency of their community are the same ones being used to destroy black life. The Kirkwood Security Patrol promises that for 96% of the $200 a year membership fee goes directly to detectives’ salaries. The remaining 4% covers administrative and other incidental costs. In 2016, residents funded some 522 hours of off-duty patrol hours (KSP Website, nd). That is a little over 10 hours a week for a neighborhood smaller than central park in Manhattan. While there are no recorded incidences of police on or off duty killing a black person, the point here is that white space is secured by the structures that threaten black life, even in communities that see themselves as diverse, inclusive, and progressive.

While white moral agents can recognize injustice against blacks and respond by proclaiming Black Lives Matter in their front yards, whiteness constrains them to contend with the way the communal institutions are born of the same concerns of the racist progenitors of these communities. In essence, if protecting and improving home and property values are of primary interest warranting the creation of institutional and structural entities, then anti-racist praxis can only go so far as to not impede on those values. History is yet framing the present, and anti-racist praxis is embodied as an individual practice while institutional and structural entities support the legacy of whiteness. Ultimately, the limit of anti-racism is that one can be engaged in anti-racist praxis in one aspect while relying on upon and reinscribing whiteness in another. In the context of these communities, you can have both a Black Lives Matter sign in your hard and pay over $1,000 to have police patrol your neighborhood, without ever reckoning with the problematic ways police will engage black bodies. Race scholar Ruth Frankenburg says, “the term “whiteness” signals the production and reproduction of dominance rather than subordination, normativity rather than marginality, and privilege rather than disadvantage” (Frankenburg, 1993, 236-237). In this way, both the conceptual, political, social, and physical formation of neighborhoods like Druid Hills and the proliferation of private policing of said neighborhoods function as forms of whiteness. The protection of property values and the political economy of desirability and implore privilege, dominance, and make normal white space as right space.

“White is the color of domination, unmarked and unacknowledged (by whites mostly) because domination works best when less is said about it and because dominance confers protection from scrutiny (there’s risk in looking critically at or speaking critically about those in power) (Catherine Prendergast and Ira Shor, 2005, 379).

Good White People and the Hegemonic Ideal

Whiteness does not have to puff itself up to maintain its dominance. That is, white supremacy can work just as readily unmarked and unacknowledged as it can in bold display. Whiteness does not have to thematize its own power to act powerfully. Prendergast and Shor’s quote intone these realities.

In this final stage, we argue that the usage of Black Lives Matters yard signs can too serve as a means of supporting and enacting whiteness; the same whiteness that was identified as a constraint. Because moral agency is understood as actions that emerge from beliefs and convictions, inherent in those acts is a kind of self-reflexivity. To be a successful and good moral agent is to act according to your convictions. It is to follow-through with your beliefs. At some level, this has to have some effect on the moral agent. The moral agent can take concrete and existential comfort in knowing they have acted following what they believe. For whites who value anti-racist praxis as a moral commitment – using the Black Lives Matter sign has the potential to inform how they see themselves as white.

This reflexivity is latent in the more prominent ‘We Believe’ Black lives Matter signs. Because these signs are not only declaring that Black Lives Matter, but also claiming them as beliefs, there is a way they are making the external an internal orientation. The making public of this internal conviction is returned to the user by the visual permanence of the yard sign. Every time they return home, they are confronted with what they believe. If the sign is achieving moral agency, then it can also be the case that the sign is achieving some form of subject- affirmation. The sign states what the user believes while also affirming to the user that they have moral courage to act on what they believe. To be anti-racist and engage in practices that one understands to be anti-racist is to lay the groundwork for seeing oneself as a good white person.

Sociologist Matthew Hughey’s work analyzing the logics of white nationalist groups and white anti-racist organizations offers us a framework to explore this point further. Hughey argues that as a formidable social category, whiteness is “ever-morphing” (Hughey, 2016, p. 213). By ever-morphing, Hughey points to the ways whiteness, on the surface, intends to hide itself. Focus then must be paid to the “patterned sets of expectations, obligations, and accountabilities that govern the racial identity performances of whites” (213). These patterns collectively give rise to what Hughey terms “hegemonic whiteness” which “constitutes a set of expectations that simultaneously constrain and guide the ongoing formation of one’s white racial identity throughout everyday social interactions” (Hughey, 213-214). In part, Hughey shows how whiteness nurtures and soothes itself. So long as whiteness is not recognized as the real moral problem, it can maintain its dominance.

While all these communities taught diversity, they do not address underlying histories of or present challenges to that diversity. Noting these kinds slippages more broadly in the diversity discourse, Hughey says, “these interracial depictions of friendly and cooperative race relations thus eschew any blatant message of white supremacy while relying on an implicit message of white paternalism and anti-black stereotypes of contented servitude, obedience, and acquiescence (Hughey, 219-220). Whether white nationalist or white antiracist, the interracial distinction requires black inferiority or subjugation be a foregone conclusion. This white paternalism can be seen in the savior complex that characterizes young white millennials moving into the educational and non-profit sector with the heartfelt desire to save black and brown youth. Diversity, multiculturalism, and inclusion rhetoric all serve to make black and brown people feel welcome while also making the whites who run and support these initiatives feel like they are using their privilege well.

The intra-racial distinctions allow some whites to position themselves over and against other whites -the good anti-racists and the bad racists. This was the move Hillary Clinton made when she called Trump supporters in the 2016 presidential election ‘the deplorables.’ These intraracial distinctions are further demonstrated in the way whites argue that hate and discrimination will not be tolerated. When said differently, this means – specific forms of white supremacy are not permissible. Neither of these distinctions challenges fundamental orientations of anti-black racism and white domination. Instead, they work primarily to inform white subjectivity. Hughey describes the coalescing of these inter and intra-distinctions like this:

First, an ideal whiteness is set apart from a set of fictional black and brown behaviors thought endemic to those racial groups. Second, the white ideal is removed from those whites that fail to acknowledge and orient themselves in opposition to the aforementioned dysfunctional behaviors (Hughey 223).

Whiteness is then constrained by a need to preserve itself by any means necessary. If this is the caldron in which white moral sensibilities are formed, then an anti-racist praxis as a moral action is constrained by these prevailing logics. Recognizing these constraints Hughey goes on to argue that whiteness obscures whiteness by leaving itself unchallenged. Whiteness as the ‘hegemonic ideal’ means anti-racist praxis need only tend to the concerns that matter to white people in such a way that preserves whiteness in some way, shape, or form.

Moral agents throughout these east Atlanta communities who use Black Lives Matter signs are ultimately positioning themselves against people in their own communities who do not share their views. In essence, Black Lives Matter yard signs mediate a discourse between white people about what kind of white people they are, desire to be, and want to see themselves as, while also signaling to black folks how good they are by supporting the cause. To be a moral agent acting in accordance when one’s values, does not preclude one for nurturing the very thing necessary for anti-black racism.

Conclusion

While moral agency, as conceived in this project, affirms the moral convictions of the moral agent, it does account for the way constraints orient the moral agent to the moral field and the efficacy of moral actions. Whiteness is a formidable constraint and is not readily undermined by a form of moral agency that is ultimately about acting consistently with what one’s moral convictions. White residents in East Atlanta, may effective voice solidarity by using yard signs, but this does not redress hegemonic whiteness and the structures that provide for the world white people want to make for themselves. Additionally, moral actions reflexively affirm a brand of whiteness for moral agents that eclipses whiteness’ essential connection to white supremacy, privilege, and normativity. Regardless of the moral agent’s personal intentions and their personal convictions, this form of moral agency allows for moral agents to celebrate the doing of something, while failing to recognize how the doing reifies white space, white values, and white propriety. Moral agents who proclaim Black Lives Matter in their yards must do more than take comfort in their proclamation. White people must think critically about their whiteness and the anti-blackness it requires.

2020 Postscript

This paper was initially written in 2017. At present, a resurgence of the Movement for Black Lives is taking place. Black Lives Matter signs are visible nearly everywhere, including the streets themselves. Even in this latest groundswell, I stand by the fundamental argument. My sense is that it is easier to affirm Black Lives Matter than it is to problematize the anti-black grounds upon which whiteness coheres. I am still concerned with the objectification of black suffering as way to achieve America or some other humanist endeavor. While declaring black lives matter serves the populist anti-racist discourse, it does little to disrupt the on-going production of whiteness and its ordering of the world. So long as we fail to calibrate the strength of whiteness itself as a moral constraint, we reify black suffering ad infinitum and I am tired of living in a world that requires black suffering in order to be a world.

End Notes

[i] http://www.asanet.org/sites/default/files/savvy/footnotes/apr03/indexthree.html

[ii] https://twitter.com/TimahRuthE/status/564979213309341696

[iii] The Anti-racism Digital Library, Glossary and Thesaurus by Anita S. Coleman – http://sacred.omeka.net/glossary

[iv] $150 for East Lake (https://www.eastlakesecuritypatrol.org/join.html)

$25-1,200+ for Druid Hills (http://www.druidhillspatrol.org/donate.html)

$100-300 for Kirkwood (https://www.kirkwoodsecuritypatrol.org/pay-dues/)

Works Cited

Druid Hills Civic Association. (n.d.). Druid Hills Civic Association – Neighborhood History. Retrieved October 2017, from https://druidhills.org/Druid-Hills-History

Druid Hills Olmsted Documentary Record: Selected Texts. (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved from https://www.druidhills.org/resources/Documents/letters-project-complete- text.pdf Druid Hills Patrol. (n.d.).

Reason One – DRUID HILLS PATROL. Retrieved October 2017, from http://www.druidhillspatrol.org/reason-one.html East Lake Security Patrol. (n.d.).

East Lake Security Patrol. Retrieved October 27, 2017, from http://eastlakesecuritypatrol.org/home.html Frankenberg, R. (1993).

White women, race matters: the social construction of whiteness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Garza, A. (2014, October 7).

A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement. Retrieved October 2017, from http://www.thefeministwire.com/2014/10/blacklivesmatter-2/ Hughey, M. (2016).

Hegemonic Whiteness: From Structure and Agency to Identity Allegiance. In S. Middleton, D. R. Roediger, & D. M. Shaffer (Eds.), The Construction of Whiteness An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Race Formation and the Meaning of a White Identity. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Kirkwood Security Patrol. (n.d.). Kirkwood Security Patrol. Retrieved October 27, 2017, from http://www.kirkwoodsecuritypatrol.org/ Linscott, C. “Chip” P. (2017).

All Lives (Don’t) Matter: The Internet Meets Afro-Pessimism and Black Optimism. Black Camera, 8(2), 104–119. Prendergast, C., & Shor, I. (2005).

When Whiteness Is Visible: The Stories We Tell about Whiteness. Rhetoric Review, 24(4), 377–385. Reid, L., & Adelman, R. (n.d.).

The Double-edged Sword of Gentrification in Atlanta. Retrieved November 2017, from http://www.asanet.org/sites/default/files/savvy/footnotes/apr03/indexthree.html