Anne Spencer’s garden cottage, Edankraal, as preserved today. Photo by Mary Ann Robertson

Anne Spencer is best remembered as a poet of the Harlem Renaissance. Between 1920 and 1935 Spencer was published widely in publications like W.E.B. Du Bois’s the Crisis and is anthologized as a significant African American woman writer. She also never lived in a major city and published her first poem when she was thirty-eight years old. She spent nearly her entire life in Lynchburg, Virginia, in the same house at 1313 Pierce Street. From this home, she wrote every day, maintained intimate, rich friendships, raised a family, and provided sanctuary and warm hospitality to Lynchburg’s Black residents and visitors. During her long life, Spencer was a beloved fixture in the local Black community and a thorn in the side of the city’s white administrators and politicians. In fact, Spencer never prioritized publishing her poetry. She practiced writing as an exercise of freedom and creative expression, and was more devoted to teaching Black students, providing access to literacy and literature, and boldly confronting and undermining Lynchburg’s segregation laws.

Anne Spencer in her wedding dress, 1900. Courtesy of James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Lynchburg is quick to claim and memorialize Spencer as a famous Harlem Renaissance poet but is reticent to acknowledge our brutal history of Jim Crow segregation and therefore Anne Spencer’s powerful resistance to it. Her life and work have powerful lessons for activism, investment in local communities, and the freedom found in art and nature. Her life also requires us to critically examine how she has been preserved and remembered. Exemplary moral agents like Anne Spencer are all around us—both here and now and in the historical record—but their stories are so often silenced, sanitized and erased from public view. Anne Spencer’s home and garden are open to the public as a beautiful museum, which reveals how historical preservation, too, is a profoundly important, ongoing exercise of moral agency under constraint. In Lynchburg, the legacy of Anne Spence tugs at our local memory. Her life of unbounded creativity and activism implores us to direct our view toward countless other constrained moral agents who persisted against the powers of white supremacy in their local communities and everyday lives.

Making a Way Out of No Way

The life and moral agency of Anne Spencer is best captured in the popular African American expression, “making a way out of no way.” This definition of moral agency has constraint built into it—acts of agency are morally relevant precisely because they undermine, subvert, and oppose the constraints placed upon them. Making a way means acting beyond, above, or altogether eluding expectations placed upon the agent by the hegemonic powers of the world. These are acts that preserve life when the powers of the world seek death; acts that embody and encourage joy when the powers of the world seek despair; acts that create opportunity and flourishing when the world seeks to limit and restrict. Amidst the constraining contexts of Jim Crow violence and segregation, Anne Spencer is an exemplary moral agent because she carved out spaces for joy in her own life and for others; she expressed the resilience of Black creativity despite limited opportunities to make a living doing so; she created networks and expanded opportunities for local Black residents in a city that wished to regulate them to the periphery with next to nothing in the way of civic resources or support.

Womanist theologian Monica Coleman takes Making a Way Out of No Way as the title of her most systematically theological book. She defines the four characteristics of “making a way out of no way” as “God’s presentation of unforeseen possibilities, human agency, the goal of justice, survival, and quality of life, and a challenge to the existing order.”1 This four-part exposition of making a way out of no way serves as a near-perfect definition of moral agency under constraint embodied by Anne Spencer and countless other agents of the Civil Rights movement, known and unknown. Spencer seized the unforeseen opportunities presented her—the opportunity to publish her poetry, to educate local Black people, particularly one new resident to the city, Ota Benga, and to curate a local movement of resistance in Lynchburg—and took up that space with confidence, fervor, and hope. The latter half of Coleman’s definition is marked by a distinctly womanist emphasis on survival and quality of life alongside the work of justice. This especially characterizes Spencer’s work along with a likely reason she is not better known. Spencer was not a nationally recognized activist or strategist; her work was local and often individual, even though it was conducted with the goal of the interior survival and flourishing of Lynchburg’s Black community in mind. The ways Spencer confronted Jim Crow in Lynchburg are often downplayed compared to her literary achievements, which is one problem. The other is the failure to see her writing itself and the interior longings it fed and expressed as equally integral to Spencer’s challenge to the white supremacist status quo, and Coleman importantly makes clear these acts of creativity and survival do profound moral work. Spencer ought to be remembered within this womanist framework, as a moral agent who consistently undermined what Emilie Townes famously calls the “fantastic hegemonic imagination,” and not made to fit a palatable narrative of respectability that divorces her poetry from her local activism, from how she made a way out of no way in Lynchburg, Virginia.2

Devoted Educator, Passionate Activist

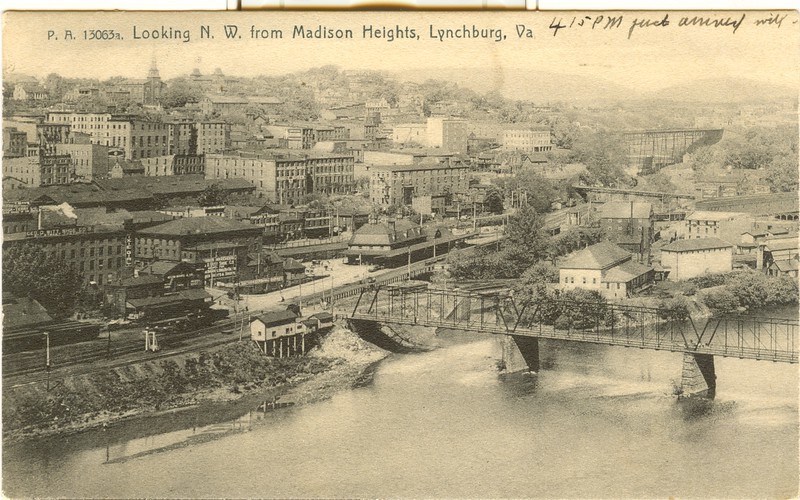

Lynchburg, Virginia was founded in 1757 by John Lynch, a Quaker who established a ferry line across the James River to reach the town. It was incorporated as a city in 1786 and its early history was at once complicated and straightforward with regard to slavery, racism, and the Civil War. It had and still has a thriving tobacco industry, and it was located on a major river, making it a key transportation hub for the antebellum economy. Its optimal location for trade also meant Lynchburg was a major stop for slave traders. As historian and journalist Pamela Newkirk puts it, “Lynchburg had a flourishing and conspicuous slave market.”3 The town itself was built entirely by enslaved labor, and the tobacco industry also owed its success to the labor of enslaved men, women, and children. At the same time, Lynchburg’s Quaker origins accommodated early pockets of resistance to slavery. Many Quakers left the town and many others actively protested slavery while also hiring free Black workers; the city also permitted free people of color to own and operate businesses. As Newkirk finds, “the first census of Lynchburg, taken in 1816, shows an overall population of three thousand, with nearly half—1,200—African American. Of the African Americans, 250, or roughly twenty percent, were free, compared with eight percent for the state.”4 So, while some of Lynchburg’s most powerful public figures were intimately and enthusiastically tied up in the slave economy—city councilors, teachers, doctors, business owners—the city also had a thriving Black community including over twenty Black churches, businesses, public schools, and larger institutions of education like Virginia Theological Seminary, at the time a co-ed primary and secondary school for Black children. Anne moved to Lynchburg on her own to attend Virginia Theological Seminary in 1893, when she was eleven years old.

Anne Spencer flourished at Virginia Theological Seminary as she dove headfirst into a humanities-centered, liberal arts education. During Anne’s time as a student, the school was headed by Gregory W. Hayes, a widely recognized educator and Presbyterian minister. Under his sixteen-year tenure Virginia Theological Seminary’s enrollment grew and the school gained a reputation for training impassioned orators, writers, and public figures. Hayes argued unapologetically for “black autonomy” and for maintaining the school’s “independence from white Baptists,” even as this drew him into conflict with his trustees and many white organizations who provided funding for the school.5 To make up this financial deficit, Hayes traveled up and down the East Coast to fundraise in large cities and recruit students. He resisted a Booker T. Washington model of education, which prescribed incremental change along with industrial training for Black people, and instead “insisted on offering the same options available to white students”—that is, more like W.E.B. Du Bois, he was “fiercely committed to liberal arts education.”6 Hayes turned Virginia Theological Seminary into the hub of Black intellectualism in Lynchburg and a nationally acclaimed institution of higher education, and Anne, while she struggled at first, quickly excelled, impressed Hayes and all her instructors, and graduated six years later at the top of her class.

Anne was heavily influenced by Hayes’s educational philosophy. As one of his star pupils, he let her in on the various challenges facing the school as a cost of staying true to his mission. She recalled to her biographer:

“Periodically the financial supporters, such as the white National Baptist Convention, sent representatives to inspect the school to determine what was going on, at which time the inspectors were shown exactly what they wanted to see: trades and industrial courses being taught. When the inspectors left, the school would exhume the briefly but conveniently buried Latin texts and literature books and decrease the number of sewing machines, ironing boards, and hammers. The typical though covert curriculum would continue.”7

Anne gleefully participated in these covert activities and remembered fondly how she and her fellow students—as well as students at Black institutions of higher education across the country— “acquired instruction in the liberal arts” through what Anne called “devious means.” 8 This lifelong, devious practice of education and learning is the first major sphere of Anne’s life aptly seen through the lens of moral agency under constraint, and the seed was planted and watered at Virginia Theological Seminary. Anne’s education in the liberal arts was accompanied by a kind of training in what womanist ethicist Katie Cannon calls “unctuousness”: “creatively straining against the external restraints in one’s life.”9 Anne applied herself diligently in school, reading Kant, the Bible, and numerous theological and classical texts, all while never losing sight of this virtue of unctuousness; she was “concerned not so much with ascertaining fact or elaborating theories as with the means and ends of practical life.”10

Anne returned to teach at her alma mater from 1910 to 1912, where she befriended and mentored Ota Benga. Benga arrived in Lynchburg at the urging of Gregory Hayes to enroll at the Seminary. He arrived from New York, where he had only recently been released from the Bronx Zoo. Benga had been purchased by a white Presbyterian missionary at a slave auction in the Congo in 1904. By 1906, he was exhibited at the Bronx Zoo, where he shared a cage with an orangutan and chimpanzees. He became an incredibly popular circus-like attraction, but the violation of his humanity attracted enough national ire to prompt his release that same year. Hayes, aware of Benga’s story, rallied to get him to Lynchburg, where Benga longed to live peacefully and assimilate into Black American life. Spencer was the first person with whom he felt at home. She taught him English and he was a frequent visitor to her home, where he felt warmly embraced by the flora of her garden. Between 1910 and 1916, Benga was involved alongside Anne in local organizing in Lynchburg. During this time period, historically recognized as the nadir of the Civil Rights movement following Reconstruction, the local government passed a number of restrictive Jim Crow laws that further segregated the city and introduced increasingly draconian consequences for violating them. Public facilities, transportation, and neighborhoods were all rigidly segregated, the effects of which are still highly visible in the city today.

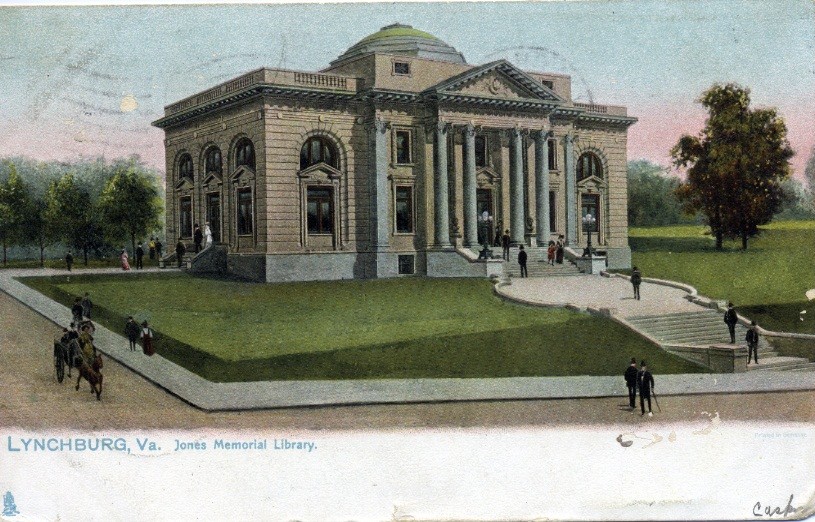

Anne Spencer’s love for literature and education took on the energy of righteous anger when Lynchburg’s beautiful Jones Memorial Library opened in 1908. The library was named after a Confederate Civil War soldier whose widow declared the library was “wholly for the use of white people.”11 This was one unjust law too many for Spencer, who in the following decade joined every committee possible to advocate for Lynchburg’s Black community. Meanwhile, the stress of assimilation and the yearning to return to his native Congo was debilitating for Ota Benga. Following his time at Virginia Theological Seminary, he moved to a predominantly white neighborhood, where he faced re-traumatizing ridicule not unlike that which he experienced in New York. He died by suicide in 1916, a tragic reminder of the “great marks” left by racial terror in early twentieth century America.12 Spencer, in the wake of Benga’s death and mounting segregation laws, was frustrated by the lack of response from the white community. With the desire for “more immediate results,” she suggested their local Black committees affiliate with the NAACP and open a Lynchburg chapter.13

The national office of the NAACP agreed to send a representative to help them set up a chapter, but there was a problem regarding where he would stay. Again, in keeping with the laws of segregation, there were no hotels in Lynchburg open to Black travelers. It was decided Anne and Edward Spencer would host the visitor; a man named James Weldon Johnson whose first visit to the Spencer house on Pierce Street would prove to be, in Spencer’s words, “one of the most significant events in [my] life.”14

Johnson’s visit would bring Anne Spencer’s interior life at 1313 Pierce Street into a larger movement. She described their meeting to her biographer another way as “an act of God,” alerting us back to Coleman’s definition of moral agency under constraint. Spencer made a way out of no way by both occasioning Johnson’s visit through her organizing endeavors and seizing the opportunities he presented her. Her publishing career gave her, her family, and her community “access to avenues outside the spiritually deadening existence in Lynchburg.”15 Spencer’s home became a thoroughfare for traveling Black intellectuals, and her reflections on nature, race, love, and faith would become canonized as part of the prolific Harlem Renaissance. Johnson and Spencer instantly connected, as she fondly remembers, “from the first, Jim and I were Jim and Anne to each other.”16 Johnson saw some of Anne’s poems lying around and asked if he could take them with him. He showed them to various publishers, who all noticed Anne’s talent. Just one year later, Anne’s first poem was published in Du Bois’s the Crisis, bringing the arc of her educational journey full circle, from her earliest love for the Du Boisian model of liberal arts education to publication in his indomitable magazine, punctuated in between by teaching, mentoring, organizing, and myriad local acts of moral agency.

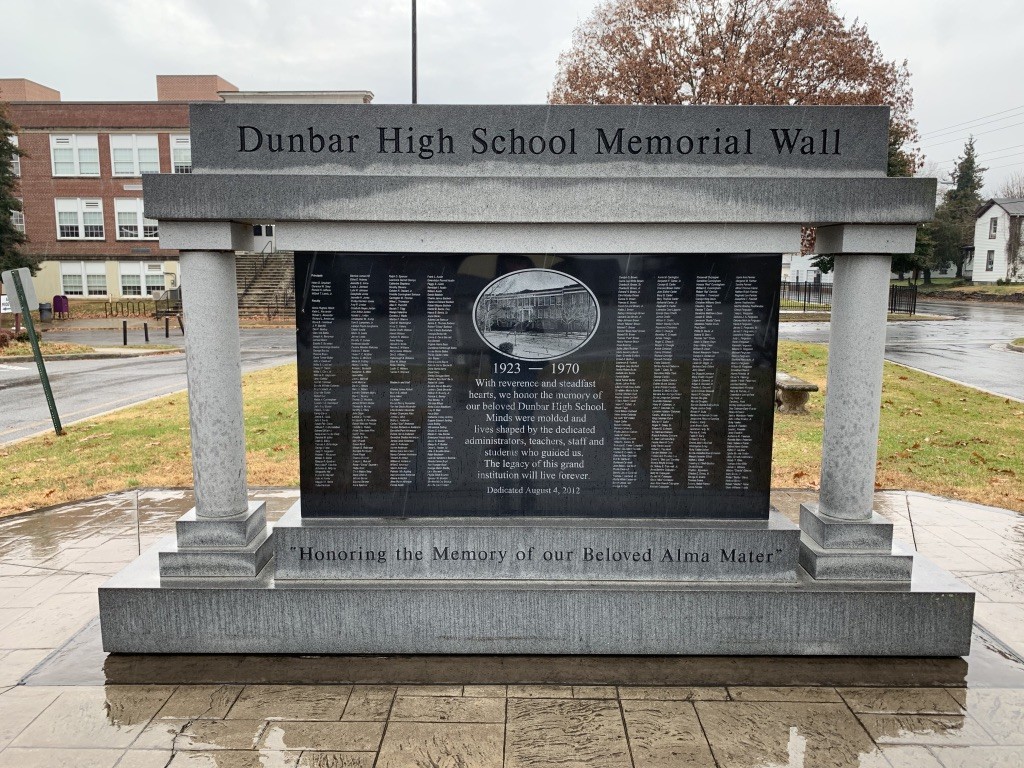

As her poetry continued to be sporadically published and her children grew older, her passion for literacy and education took a new form in her life. She was determined to send her children North to get their college education, but that meant taking on more financial burden. In order to supplement the family’s income, Spencer decided to try her hand at being a librarian. While the money was necessary, her biographer surmises “it is likely she decided to apply for the job at the library before she decided to earn money, for the urge to have better access to books outweighed the desire for additional income.”17 This longing for access to literacy and literature is perhaps the most moving phase of Spencer’s local activism and subversive moral agency. Anne, still simmering with indignation over the city’s segregated library, was hired in 1924 by the Jones Memorial Library board of trustees to oversee the library’s Black branch, which was located in the new Black high school, Paul Laurence Dunbar High.

In her role as librarian at Dunbar—a position she held for over twenty years—she transformed it from a glorified closet into a fully functioning library. She immersed herself in the school’s operations, often substitute teaching when necessary, and petitioned her prominent literary friends like Johnson and Du Bois to send more books specifically geared toward Black children. She tutored students to improve and broaden their reading and was recognized as an exceptional researcher by her colleagues across the city. The original room Spencer was provided for the library contained three books—she immediately supplemented the meager collection with her own personal books and “pressed Jones to do more than it otherwise would have done” in terms of providing resources to its Black branch.18

Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, c. 1930. Courtesy of the Lynchburg Museum System.

People listened when Anne Spencer made demands. By the mid-1920s she had not only made her name as a published poet but had been organizing with the NAACP and other organizations in Lynchburg for over a decade, with a special passion for the school system. She was well-known across town—beloved by Blacks and repudiated by many whites—for “waging a boisterous and ferocious battle against the town’s Jim Crow practices.” This “local notoriety” emerged first in Spencer’s campaign to get white teachers replaced at the Black high school that preceded Dunbar. While she had been working within the Black community since her arrival in Lynchburg, this particular effort is what put her on the radar of Lynchburg’s white residents. She “bombarded the local paper and public offices” with letters from the Black community and wrote her own forceful letters demanding the hiring of Black teachers to educate the school’s Black students.19 She defied the local politics of respectability, preferring pants to dresses and often wearing her hair down. Another inspired protest of Spencer’s was her improvisational approach to transportation. Now needing to commute to work every day, she ardently refused to support the city’s segregated public transportation by paying for it. Instead, she would walk or take a taxi, or more conspicuously, she would “hitch a ride on some of the grocery wagons,” just grabbing onto the back and jumping off when she was close enough to her destination.20

Two unidentified men stand in front of a Lynchburg bus c. 1940. Lynchburg’s public transportation was privately owned–and segregated–until 1974, when the city took it over. Courtesy of the Lynchburg Museum System.

Despite Anne Spencer’s relative loneliness during her coming of age years and the emphasis on privacy and interiority in her poetry, around Lynchburg, “few people…would expect a black citizen other than Anne Spencer to be courageous enough to voice dissent and indignation concerning the racially restrictive practices of the town.”21 Anne’s private sensibilities did not prompt a retreat from public life; they simply made her public personality more fiercely independent than segregationists in Lynchburg bargained for. Greene, summarizing Anne’s personality in relationship to her public activism, aptly uses the language of freedom and constraint: “always asserting to the fullest extent possible her rights as a free human being who adhered to few societal constraints, Anne Spencer could be called an individualist but never a selfish person.”22 Under constraint that would not seem to break, Spencer, in her impressive ninety-three years of life, exhibited an infinite plethora of tactics to undermine Jim Crow in Lynchburg. Her local acts of agency chipped away at these violent structures with “the relentless and timeless force of water on the rock of entrenched evil.”23 Anne Spencer’s moral agency was not just exercised on behalf of other people; she cultivated space for her own health and joy and that of her family and intimate friends that sheltered them from the brutality beyond her fence. She recognized the importance of protection, solitude, and retreat as much as she committed herself to protesting Jim Crow—this happiness and security was found in Anne and Edward’s garden.

Creative Expression and Freedom in the Garden

Anne Spencer’s poetry spoke profoundly to the perplexing context of racism. Heavily influenced by the beauty of the natural world, she could not understand why that which was beautiful and colorful, was subjugated under what was cold and white, as she opens one of her most famous poems entitled, “White Things”:

“Most things are colorful things—the sky, earth, and sea.

Black men are most men; but the white are free!

White things are rare things; so rare, so rare

They stole from out a silvered world—somewhere.”24

Much of her poetry makes this connection between blackness, beauty, growth, and life. In this way, the content of her poems expresses very literally the idea of moral agency under constraint, of flourishing in a world that does not want you to flourish, which as Spencer herself is concerned, is our loss. Strikingly vivid in its interpretation of moral agency under constraint, Spencer’s early poem, “Substitution,” addresses the power of imagination and thought to transport us from a brutal reality to a new, more beautiful one:

“As here within this noisy peopled room, my thought leans forward…quick! You’re lifted clear of brick and frame to moonlit garden bloom.”25

Through her poetry, Anne carved out spaces of beauty and refuge amidst her harsh, segregated surroundings. Greene describes her as a “private poet,” a label many literary critics have given to her: “her poetry, a private record of her attitude toward life, mirrors in poetic form the ideas and themes which shaped her life and personality.”26 While this is true, she was also certainly a protest poet. Her writing expresses total incredulity about the racism that surrounded her and even at times anger at the opportunities and pleasures denied her. In fact, Spencer claimed a stanza of “White Things” was deleted before publication due to its denigration of white men. This constraint of censorship was common among Harlem Renaissance writers, who were forced to write with caution about racial protest. Spencer believed she was heavily censored throughout her publishing career, claiming she received feedback from editors, critics, and even friends that it was “untimely and unwise” to focus to much on racial tension, especially for “a new black writer dependent on others for publication.”27 This dependence on editors and publishers was certainly a constraint placed upon Anne’s poetry writing, but upon learning she never intended to publish her poetry, we can see how she ultimately defied these constraints in her apathy about fame and notoriety.

This indifference to fame is especially and humorously evident in an exchange of letters with James Weldon Johnson. Johnson wrote Spencer declaring he believed “Anne Spencer”—her married name—to be the best pen name for her published work. She responded to Johnson, “I like the pen name—really I like everything that belongs to me!”28 This line from Spencer in a simple letter to a friend concisely encapsulates how her poetry exemplifies moral agency under constraint—it belonged to her. Every piece of her writing, published and unpublished, spoke to the depths of her interiority and the longings of her family and local community. Those who wished to censor or deny her were of no consequence, because her poems truly lived within her private pages. Writing was a practice of survival; a way Spencer nourished her own spirit in a world attempting to keep her down at every turn. Even in more mundane moments, when she just needed a break from the duties of marriage and motherhood, her pen and paper were there to help her to imagine alternative possibilities.

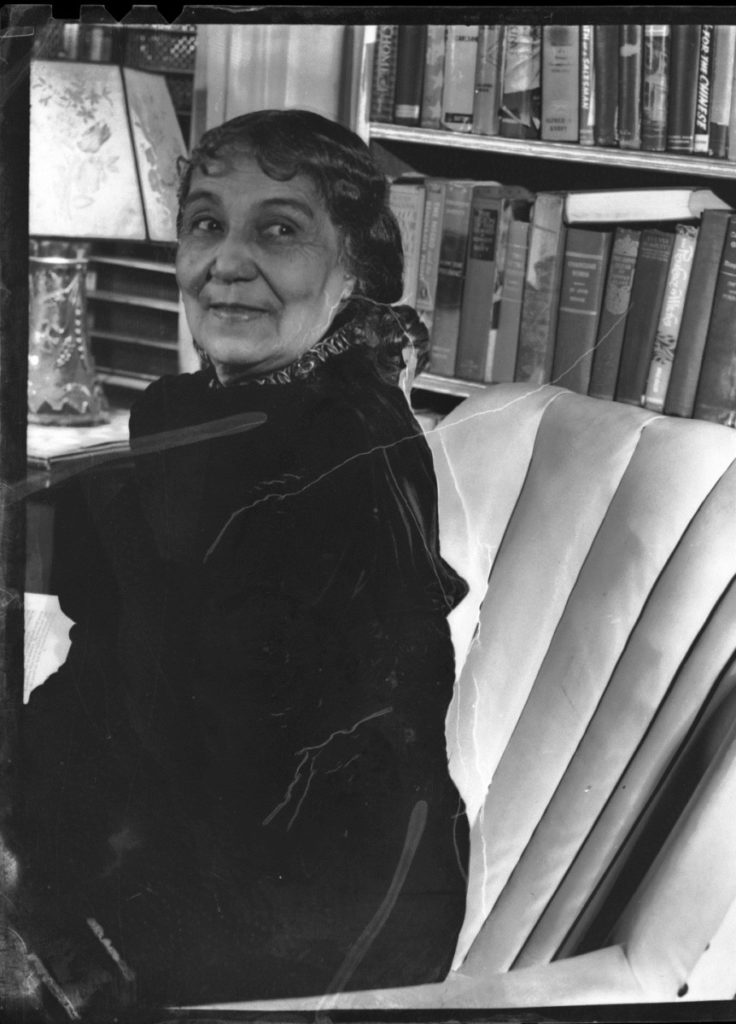

Anne Spencer later in life, seated in front of a bookcase at 1313 Pierce Street. Courtesy of the Smith Collection, Lynchburg Museum System.

But the publication of Spencer’s poetry, even though she never intended it, was also a part of a web of alternative possibilities—her writing reached countless young Black readers across the country working against racism and Jim Crow. It is impossible to know just how many lives she touched with her words; whether she provided comfort to people who were tired from the struggle, or if she galvanized young writers and organizers to keep going, it is certain her words left a mark beyond Lynchburg. Spencer is part of a Black women’s literary tradition that continues to inspire theological and ethical reflection. Katie Cannon takes Black women’s literature as a primary source for understanding the moral life because it “provides a rich resource and cohesive commentary that brings into sharp focus the black community’s central values, which in turn frees black folk from the often-deadly grasp of parochial stereotypes.”29 This was certainly an accomplishment of Anne Spencer’s poetry, as she at once captured the cultural values and wisdom of her community, expressed the complexity of her own identity as a Black woman, wife, and mother, and articulated visions of a future that undermined the constraints of the present.

Anne Spencer’s home and garden should be considered the grounding of her entire moral life and the connective tissue between her activism, writing, and passion for education. 1313 Pierce Street and its lush garden served as both a place of radical hospitality and a precious personal sanctuary. Anne and Edward both found immense joy in entertaining guests and provided plenty of food, whiskey, and compelling conversation to the Black intelligentsia passing through Lynchburg between New York, Washington, D.C., Atlanta, and other major cities. Anne and Edward made Lynchburg “an oasis in a desert of public racial discrimination” for their visitors, which included James Weldon Johnson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Langston Hughes.30 Over the years their home became not just a stopover but a destination for out-of-town visitors who became dear friends. They often hosted local pillars of the Black community, and left white residents of Lynchburg impressed by their home and hospitality. No one could avoid acknowledging the Spencers’ importance in the social and political scene of downtown Lynchburg.

The house at 1313 Pierce Street was where Anne lived and took care of her family, but the garden and its one room guesthouse built by her husband were where she took care of herself, where her creative spirit was truly nourished. The garden cottage was named Edankraal, a combination of her and her husband Edward’s names and the Afrikaans word kraal, which meant “enclosure” and was also the name of a particular southern African village. This was where guests would stay and where Spencer would do her writing, all with the garden in full view. The garden itself was massive, beautiful, and meticulously tended. One universal theme in all her poetry was allusion to nature and a deep affinity for the beauty of the natural world, and this inspiration came entirely from her garden. Just some of the plants she featured included lilacs, poppies, daises, peonies, honeysuckle, chrysanthemums, nasturtiums, petunias, sweet peas, snapdragons, and tiger lilies. Through her garden and her writing, which took up most of her time, she “enjoyed the life of leisure and reflection which her temperament required.”31 She mentions her garden or elements of nature and the divine in almost every poem, like in “For Jim, Easter Eve,” written for James Weldon Johnson:

“If ever a garden were Gethsemane,

with old tombs set high against

The crumpled olive tree–and lichen,

This, my garden has been to me.

For such as I none other is so sweet:

Lacking old tombs, here stands my grief,

And certainly its ancient tree.

Peace is here and in every season

A quiet beauty.

The sky falling about me

Evenly to the compass…

What is sorrow but tenderness now

In this earth-close frame of land and sky

Falling constantly into horizons

of east and west, north and south;

what is pain but happiness here

amid these green and wordless patterns,–

indefinite texture of blade and leaf:

Beauty of an old, old tree,

Last comfort in Gethsemane.”32

Her private, restorative practices in the garden sustained her activism and teaching; these acts of moral agency took different methods and fed different parts of Spencer’s soul, but they both necessarily contributed to her remarkable legacy.

Historical Preservation and Remembrance

Anne Spencer’s legacy, outside of anthologies which include her published poetry, is most thoroughly collected in the Anne Spencer House & Garden Museum at 1313 Pierce Street in Lynchburg, VA. The home was designated a historic landmark one year after Spencer’s passing in 1975. The work of maintaining this space is itself a collective act of moral agency. Local journalists, professors, and Spencer’s family work to maintain the museum and the garden. Yet, as a student of Lynchburg’s public schools from K-12, I never took a field trip to the Anne Spencer House; instead, my schools opted for trips to more well-known historical sites in Richmond, Appomattox, or Washington, DC. The Jones Library, now closed, never publicly acknowledged her essential role in the Lynchburg library and education systems. In addition to being overlooked locally, Spencer’s inventive elusions of Jim Crow laws and protests of the inadequacies of education for Black youth are not part of the national narrative of the Civil Rights movement.

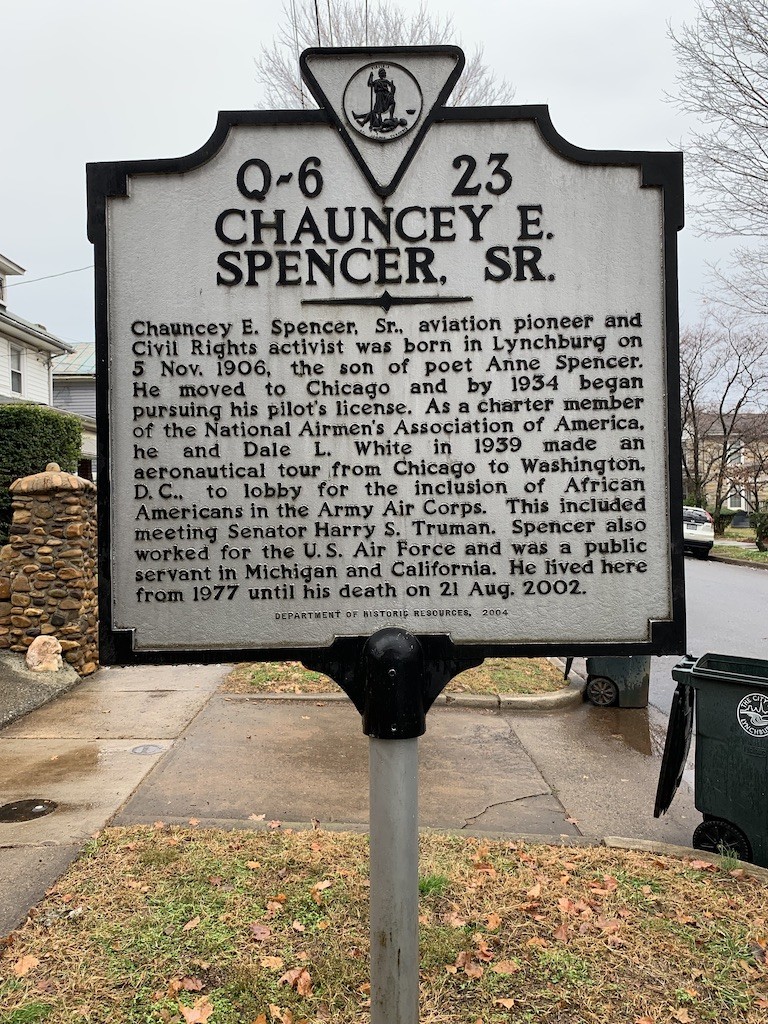

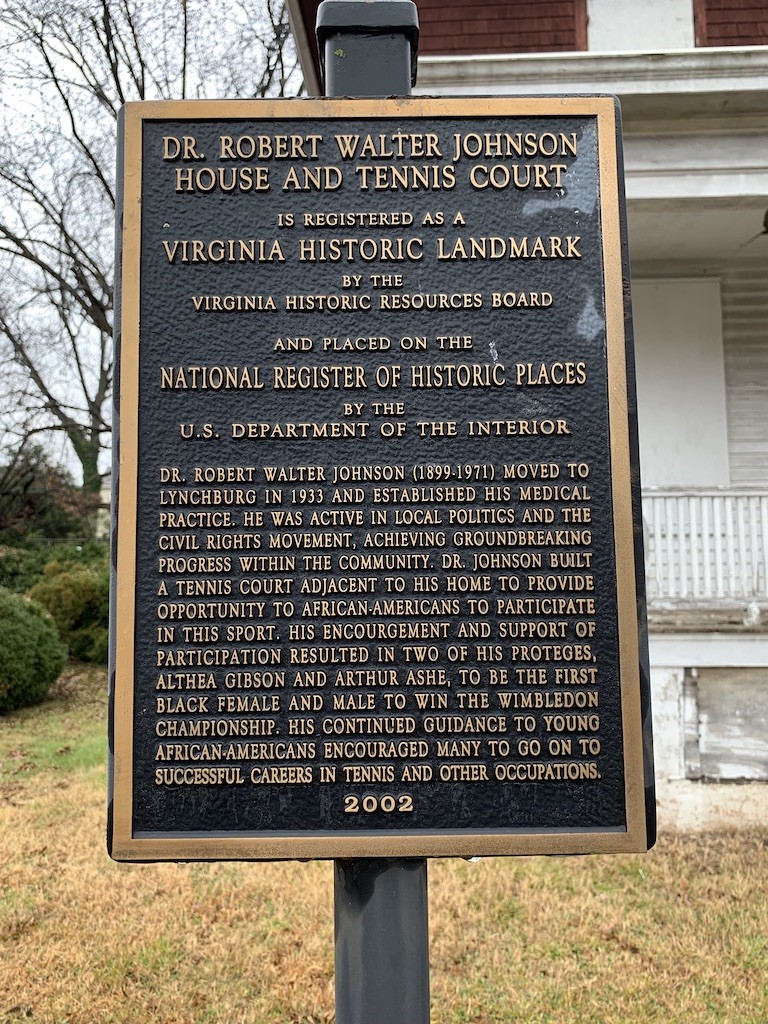

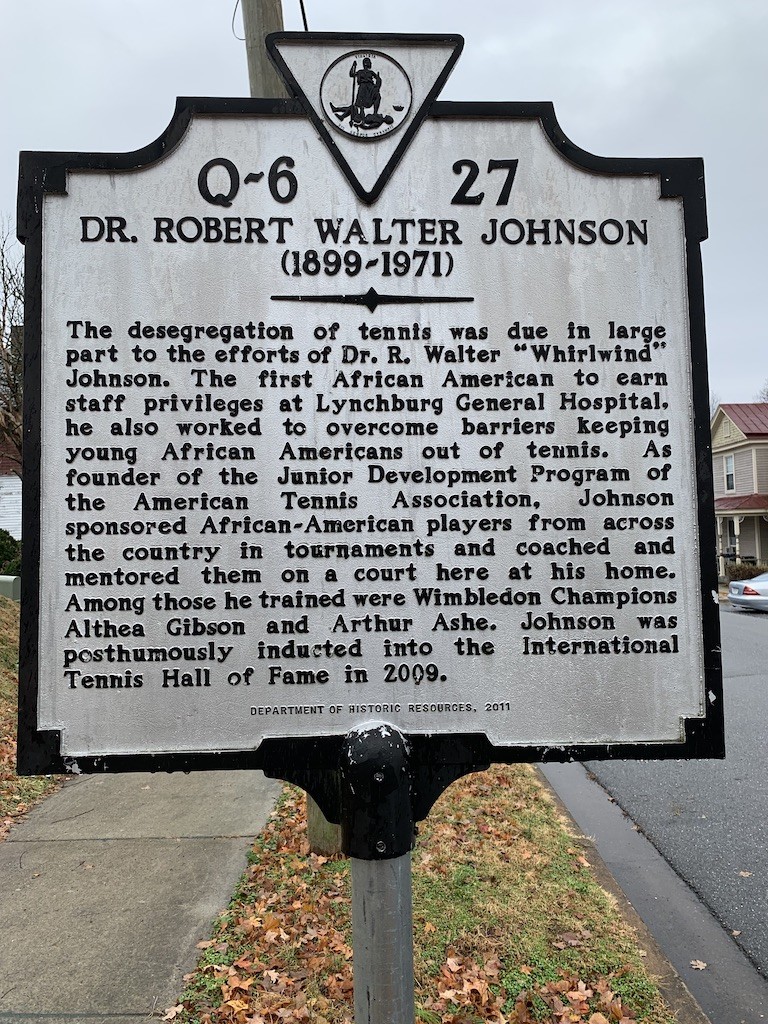

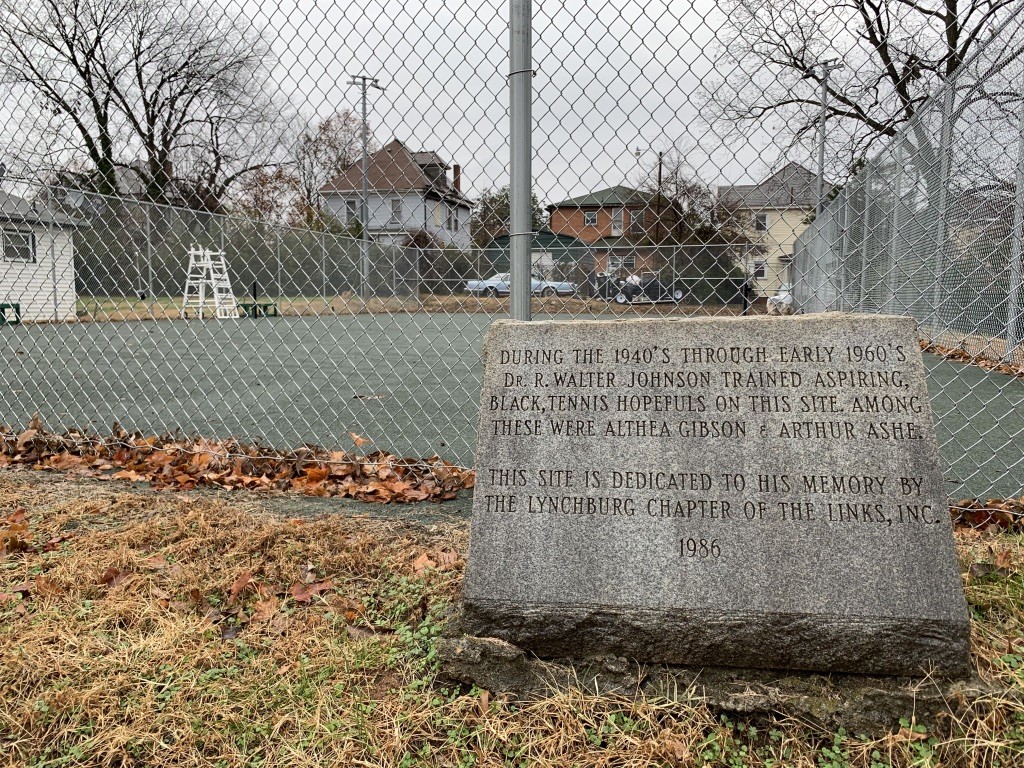

I visited the Museum this past November, on a cold, drizzly day—not ideal for a garden walk—but I was still struck by the solitude and beauty of the Spencers’ home and garden. The space is large and long, with awnings, birdhouses, and two fountains. The garden is sloped just enough so from the top of the garden—where Edankraal is located—you can see into downtown Lynchburg, and from the bottom, you can see the entire garden and up to the house. Two blocks of Pierce Street are preserved as a historic district. Here lived Anne and Edward Spencer, their son (who went on to become a founding member of the Tuskegee Airmen), and Robert Walter Johnson, a legendary tennis instructor who trained Arthur Ashe and Althea Gibson, the first African American man and woman to win Wimbledon. Darrell Laurant, a prominent local journalist in Lynchburg, has worked to keep Spencer’s legacy alive along with those of the many incomparable Black leaders, writers, and educators who lived on the 1300 and 1400 blocks of Pierce Street.33 Today, these two blocks are punctuated by historical markers; some of the houses are presently lived in, some are boarded up, others have been demolished. Down the street, walking distance from the Spencer home, is Dunbar Middle School, which is still comprised of buildings from the original Dunbar High School. Restoration of the homes and stores on Pierce Street is ongoing, but is certainly constrained by difficulties in fundraising, public awareness, and ongoing racism and geographic segregation in Lynchburg. Some photographs of the neighborhood can be found below.

Commemorating wall of Dunbar High School, which operated from 1923-1970. Was then integrated and turned into Dunbar Middle School, still operating today. Anne Spencer is listed under “Faculty.”

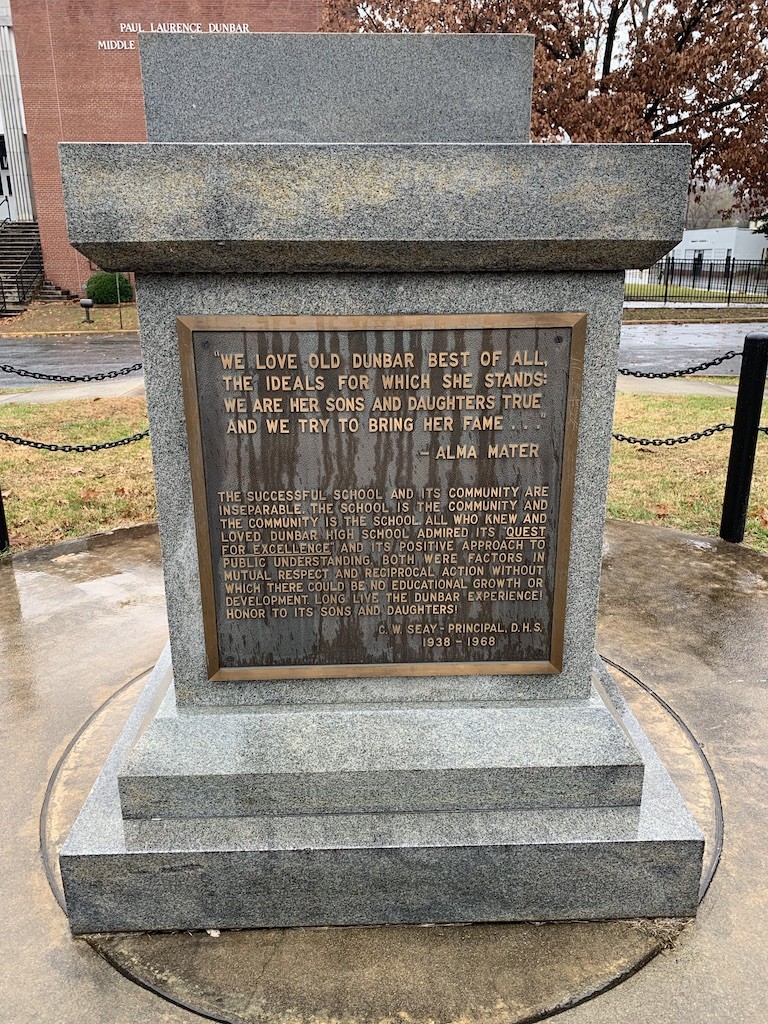

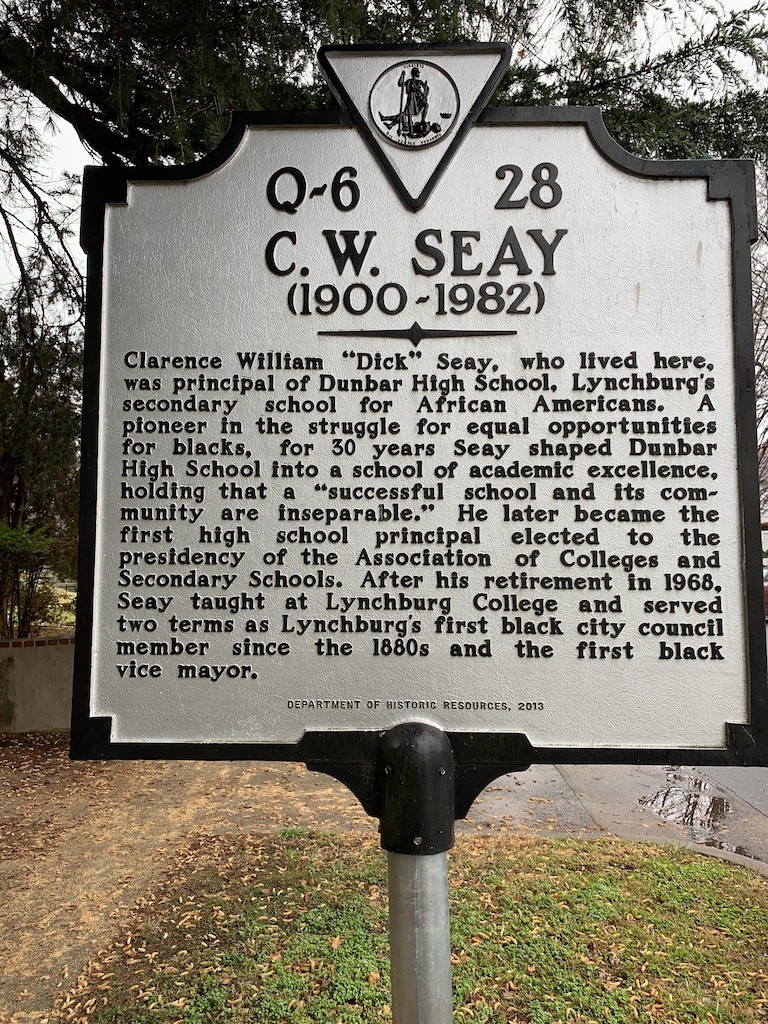

Another commemorative monument with a quote from former principal, and the Spencers’ neighbor, C.W. Seay.

Dunbar Middle School, present day.

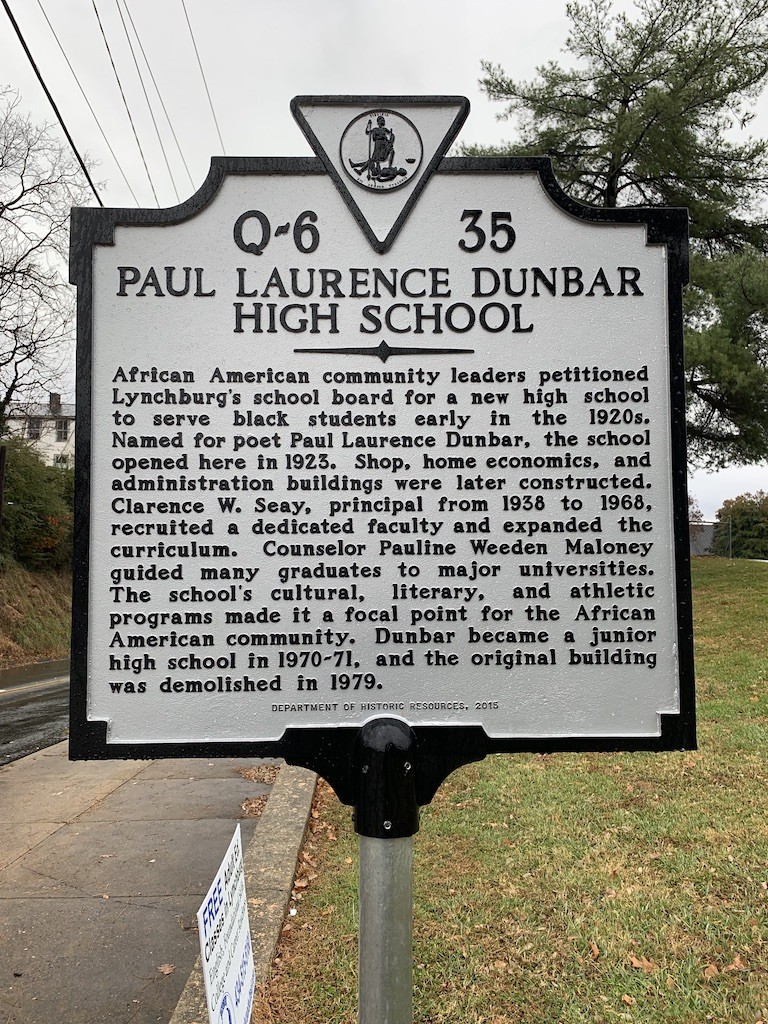

Dunbar High School historic marker.

The top of Pierce Street, a two-block historic section of Lynchburg, where all the following homes and sites are located.

The Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum (taken from Pierce Street).

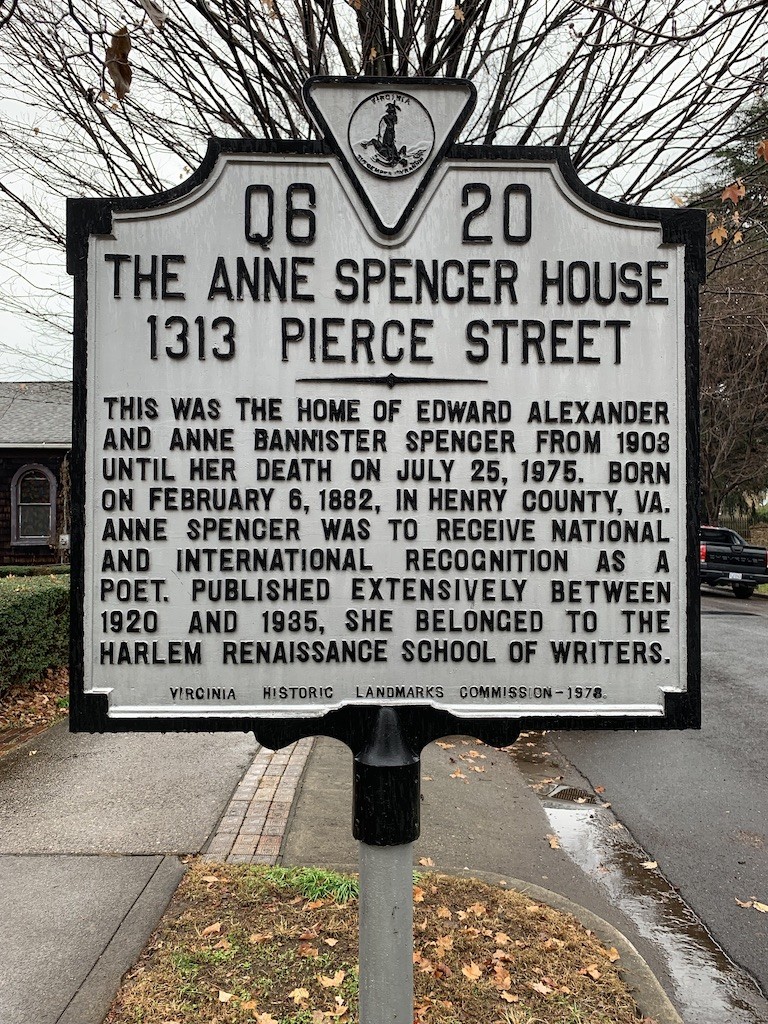

Spencer House historic marker.

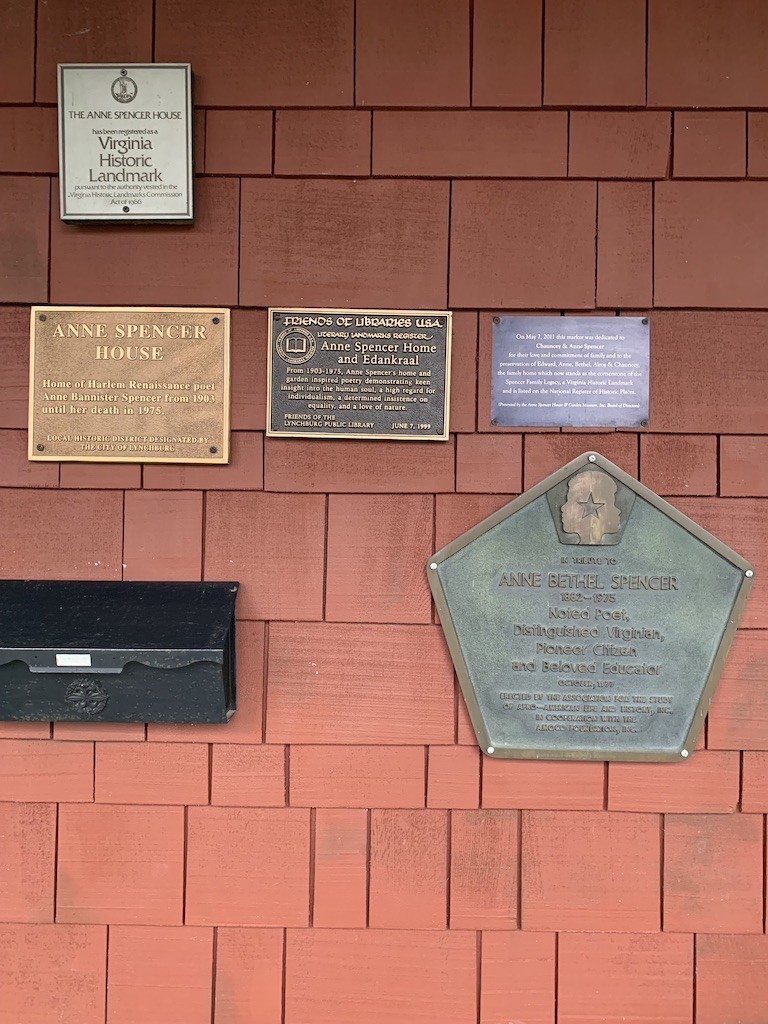

Various historical designations given to the Anne Spencer House.

Anne’s desk inside Edankraal.

Edankraal and the back of the Spencers’ house.

The garden from the back fence.

Site of the local grocery and general store, operated by members of the Spencer family from 1900 onward. This was one of the first black-owned and operated stores in the city. The apartments above the store were home to Ota Benga for a short time in 1910. In 2009, the Spencer family began restoring the building.

Chauncey Spencer historic marker.

Chauncey’s house.

Johnson home and tennis court historic marker from the National Register for Historic Places.

Robert Walter Johnson historical marker.

Johnson’s tennis court, where Arthur Ashe and Althea Gibson trained.

Johnson’s house.

C.W. Seay historic marker.

Seay house.

I was born and raised in Lynchburg, and I never visited the Anne Spencer House until I was in college, after coming across her work in a class unit on the Harlem Renaissance. The year Anne Spencer died, 1975, my father was a student at the newly integrated Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. In fact, he was the editor-in-chief of the school paper, which printed a feature memorializing her. Upon important anniversaries, now and then, the local paper will print kind words of remembrance, and Laurant has especially tried to bring attention to Lynchburg’s participation in the Harlem Renaissance and Civil Rights movement. But questions remain: Why does she not occupy a more elevated position in larger histories of the Civil Rights movement, and especially in the local scene of Lynchburg? Why isn’t the city quick to claim Spencer as a moral exemplar? When she is uplifted locally, along with Ota Benga, the contexts of constraint and the viciousness of Jim Crow segregation in Lynchburg are problematically minimized. I posit if historians took the framework of moral agency under constraint more seriously, Anne Spencer’s life and work might be more accurately and reverently preserved. Spencer’s moral life delivers to us an imperative to interrogate and explore our own local histories. The writing and canonizing of both history and ethics have for too long been done with a priority on either an unbounded, free moral agent, or a tragically, hopelessly constrained one. Anne Spencer’s consistent and imaginative acts of moral agency under constraint and her unceasing efforts to make a way out of no way reveal the moral necessity of right remembrance and gesture toward new paradigms for responsibly producing and consuming history. May we continue to investigate our familial, local, and national narratives and find, preserve, and honor the constrained moral agents who came before us.

Want to know more about this author? Click here?

Footnotes

- Monica Coleman, Making a Way Out of No Way: A Womanist Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2008), 33.

- Emilie Townes, Womanist Ethics and the Cultural Production of Evil (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 13.

- Pamela Newkirk, Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga (New York: HarperCollins, 2015), 217.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 218

- Ibid.,220

- J. Lee Greene, Time’s Unfading Garden: Anne Spencer’s Life and Poetry (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1977), 27. This is the only full-length biography of Spencer, written by Greene first as his dissertation and then later published. He was able to conduct one-on-one interviews with Spencer shortly before her death, and Spencer’s personal reflections guide the book. Greene—a lifelong faculty member in English at UNC Chapel Hill—passed away in 2017, before a second edition of the biography could be published, which the Spencer estate says is currently in progress.

- Ibid., 27-28.

- Katie Cannon, Katie’s Canon: Womanism and the Soul of the Black Community (New York: Continuum, 1996), 92.

- Ibid., 80-81.

- Newkirk, Spectacle, 227.

- Kidada Williams, They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I (New York: NYU Press, 2012), 7.

- Greene, Time’s Unfading Garden, 48.

- Ibid., 50.

- Ibid., 67.

- Ibid., 49.

- Ibid., 82.

- Ibid., 84

- Ibid., 87

- Ibid., 89.

- Ibid., 88.

- Ibid., 90

- Townes, Womanist Ethics, 163.

- Anne Spencer, “White Things,” Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races, XXV (March 1923), 204.

- Spencer, “Substitution,” in Caroling Dusk: An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets, ed. Countee Cullen (New York: Harper, 1927), 48.

- Greene, Time’s Unfading Garden, 126.

- Ibid., 140.

- Ibid., 53.

- Katie Cannon, Black Womanist Ethics (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1988), 77.

- Greene, Time’s Unfading Garden, 67.

- Ibid., 46.

- Spencer, “For Jim, Easter Eve,” in The Poetry of the Negro, 1746-1949, eds. Langston Hughes and Arla Bontemps (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1949), 65.

- See Darrell Laurant, Inspiration Street: Two City Blocks that Helped Change America (Lynchburg, VA: Blackwell Press, 2016).

Well thought out and written, full of historical nuggets that resonate today. An excellent read for anyone wanting to grow individually and educate themselves about a true pioneer.